With the world’s attention naturally attuned towards first Gaza and then the Red Sea, it has been easy to overlook an equally important ongoing news story farther east: China’s ongoing economic collapse.

The most immediate piece of economic bad news to hit the Middle Kingdom was a Hong Kong court ordering that Evergrande, once China’s largest property developer, be liquidated.

Property developer China Evergrande Group has been ordered to liquidate by a Hong Kong court, bringing an end to the yearslong saga of a company whose default rippled through the world’s second-largest economy.

The liquidation order came despite an 11th-hour push by the company’s creditors to reach a deal over the weekend, according to people familiar with the matter. It comes more than two years after the company defaulted on its dollar bonds, becoming one of the first dominoes to fall in China’s beleaguered real-estate sector.

“The time is for the court to say enough is enough,” said Judge Linda Chan in Hong Kong’s high court.

The Evergrande saga has been far more than just the story of one corporate bankruptcy. As I detailed when the company’s problems began to attract global notice in 2021, the company was the leading indicator of the extent to which China had become—actually had always been—the “Sick Man of Asia”.

Even if all of Evergrande’s assets are purchased by China’s SOEs, that would not provide enough cash to make all of Evergrande’s creditors whole; that would not provide enough cash to sustain the many businesses whose existence is threatened by Evergrande’s non-payment of bills. No matter what diktats Xi Jinping issues, without cash, a good portion of Evergrande’s suppliers and creditors will go under.

Evergrande is a stark demonstration of the limits of Beijing’s economic power, and a stark reminder of how markets are corrupted by ignoring the limits of government to rescue them from their own excesses.

Evergrande has been a corporate collapse story that has been equal parts Lehman Brothers and Enron, and like both of those titants of American business, its day has finally ended in a bankruptcy court being sold off to the highest bidder.

Yet, as the world has seen since Evergrande began its long death spiral into non-existence, the company not been the only a symptom of a much larger rot within the Chinese economy. In virtually every other aspect as well, China’s economy is not merely contracting, but collapsing.

The “front line” of China’s economic collapse has been well documented as being China’s former economic mainstay, its housing sector.

The unwavering belief of Chinese home buyers that real estate was a can’t-lose investment propelled the country’s property sector to become the backbone of its economy.

But over the last two years, as firms crumbled under the weight of massive debts and sales of new homes plunged, Chinese consumers have demonstrated an equally unshakable belief: Real estate has become a losing investment.

This sharp loss of faith in property, the main store of wealth for many Chinese families, is a growing problem for Chinese policymakers who are pulling out all the stops to revive the ailing industry — to very little effect. The troubles of the country’s real estate sector were laid bare on Monday when a Hong Kong court ordered China Evergrande to wind up operations and liquidate the company, which is saddled with over $300 billion in debt.

The property sector began to unravel in 2020, when Xi Jinping introduced his now recanted “Three Red Lines” for property developers, seeking to rein in speculative indebtedness by those same firms. Unfortunately, Xi closed the barn door long after the horse had fled clear into the next county, forcing the government to steadily walk back the restrictions on corporate indebtedness.

In an effort to stave off a broader banking crisis spurred by a growing wave of mortgage defaults (the inevitable consequence of refusing to make payments), the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission has asked lenders to extend still more credit to embattled developers, in order to facilitate completion of housing projects and thus halt the boycott wave.

China’s banking regulator has asked lenders to provide credit to eligible developers so they can complete unfinished residential properties after home buyers stopped paying mortgages on at least 100 projects across 50 cities.

There is no small irony in Beijing making this move, as the developer crisis was catalyzed by the introduction in August of 2020 of the “Three Red Lines”, a set of financial metrics meant to curb debt growth among real estate developers.

By the summer of 2022, it ws clear that the collapsing property sector was going to claim more than just Evergrande, as one of China’s other large developers, Country Garden, also began to show signs of insolvency—and which is even now trying to sell of large assets in a somewhat desperate attempt to raise cash.

Embattled Chinese property developer Country Garden is selling properties in Guangzhou, aiming to raise 3.8 billion yuan ($530 million), according to an asset transaction platform.

The properties include a hotel resort, four office towers, a shopping mall as well as five rental apartment buildings, according to listings dated Jan. 19 on Guangzhou Enterprises Mergers and Acquisitions Services.

A growing sentiment among professional investors is that the handwriting is on the wall for Country Garden as it has been for Evergrande.

Now, the question is whether Country Garden will also be liquidated in the coming months. I believe that a court will order the company to be wound up because of its huge debt, weak sales, and substantial losses. Besides, the company has already defaulted on its debt and has been downgraded by key ratings agencies like Moody’s and S&P Global.

A company in such a situation has several options. In most cases, it could sell assets in a bid to raise capital. In Country Garden’s situation, it has already sold one of its malls in a $420 million deal and used these funds to pay some of its debt. The challenge is that the outstanding debt is so high that asset sales may not be enough.

Ultimately, the answer is very likely “yes”, and for the same reason—Country Garden’s liabilities greatly exceed the market value of their assets.

Compounding the problems surrounding the Chinese real estate market—the single largest real estate and asset market in the world—is the reality that 70% of all Chinese household wealth is tied up in real estate. The collapse of China’s real estate market means within that 70% of household wealth is a level of wealth destruction that exceeds anything experienced in this country either during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis or the 1930s Great Depression.

It does not take any Nobel Prize in economics to realize this has grave implications for the stability of China.

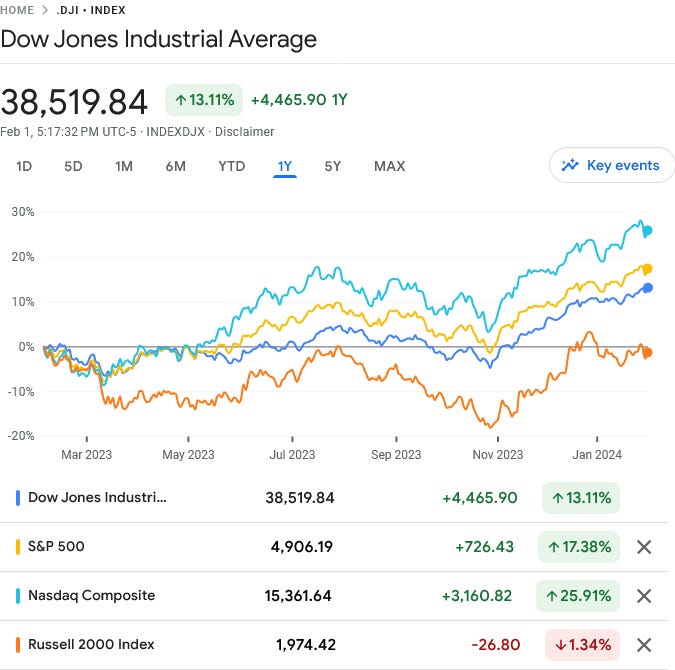

Nor are China’s problems confined to just real estate. Over the past 12 months, China’s stock markets have lost nearly one-quarter of their value.

By comparison, the US stock markets have risen in value over the same period.

So have European stock markets out performed China over the past 12 months.

What is driving the downward trend in Chinese stocks? There are several factors, but the most recent challenge has been a contraction with China’s manufacturing base.

China's manufacturing activity contracted for the fourth straight month in January, an official factory survey showed on Wednesday, suggesting the sprawling sector and the broader economy were struggling to regain momentum at the start of 2024.

The official purchasing managers' index (PMI) rose to 49.2 in January from 49.0 in December, driven by a rise in output but still below the 50-mark separating growth from contraction. It was in line with a median forecast of 49.2 in a Reuters poll.

Since early 2022, China’s manufacturing industries have been in a near constant state of contraction, according to their own National Bureau of Statistics.

By comparison, while the US manufacturing sector has been in contraction for most of 2023, post-pandemic manufacturing in the US actually enjoyed something of a renewal.

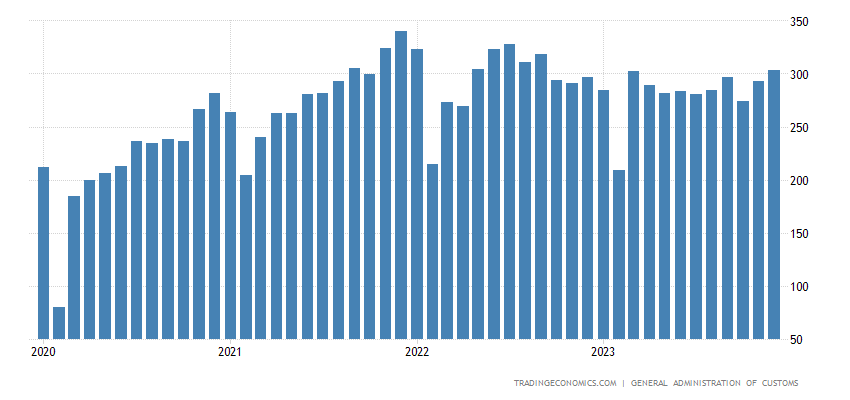

One consequence (and also cause) of the Chinese contraction in manufacturing: a decline in export value and volumes.

This data does not take into account the increase in shipping rates on Chinese goods brought on by the Houthi missile mischief in the Red Sea.

Where freight rates are moving substantially higher is in the Shanghai Containerized Freight Index, which tracks shipping rates outbound from ports in China—another presumptive Iranian ally.

If we drill into the index, we see that the increase is largely due to increased shipping rates to Europe, with US West Coast shipping showing a much smaller increase.

Problematic passage through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal due to Houthi activity is the obvious explanation for the different trends in shipping rates. With much of the Asia shipping traffic to the US East Coast having been rerouted through the Suez Canal instead of the Panama Canal in 2023 due to a drought in Central America, even shipping to the US East Coast has risen dramatically since the beginning of December.

Increased shipping costs means Chinese export volumes will fall even further as 2024 gets underway, further straining the Chinese manufacturing sector. When no one wants to buy or pay for incresed shipping, sales drop, and that means for China that exports also drop.

China’s youth employment data is another area where the numbers continue to look grim even after Beijing’s “corrections”.

The Chinese statistics bureau reported last week that unemployment among the 16- to 24-year-old demographic was 14.9 percent in December.

This would be a considerable improvement over the 21.3 percent reported for that age bracket last June, compared to 5.2 percent for the general population.

China's statistics bureau didn't immediately return Newsweek's request for comment.

A major flaw in the data: China arbitrarily excludes students and counts those young people who work as little as one hour per week.

Not so fast, said Elliott Fan, graduate director of National Taiwan University's Department of Economics. "The decline [in unemployment] was caused by China's National Statistics Bureau removing students from the sample, not because of any solid improvement in the youth's labor market," he told Newsweek Friday.

Fan listed three more swaths of society whose exclusion further throws the data into doubt.

Those working as little as one hour per week were still considered to be employed, which "does not accord to international standards for calibrating unemployment rate."

The report excluded people who, discouraged by dim job prospects, have given up.

The statistics bureau surveyed only those living in urban areas.

This suggests a crisis that is here for the long-haul, Fan said. "The Chinese government does not have any powerful tool to address unemployment, even if they want to. The surging unemployment is going with the adverse macroeconomic shocks, which are structural and likely long-lasting."

If China does not have an effective means to reduce youth unemployment, that means that China does not have a means to ensure the next generation has adequate job skills to ensure productive civic society can be maintained.

Even with the corrections, China’s youth unemployment is still an eye-watering 14%.

Given the size of China’s population, a youth unemployment rate of nearly 15% means several million Chinese youth are out of work—a distinctly bad omen for any economy. Without youth employment China cannot sustain the manufacturing and export economy that has powered the Chinese economy for decades—and right now China cannot sustain youth employment.

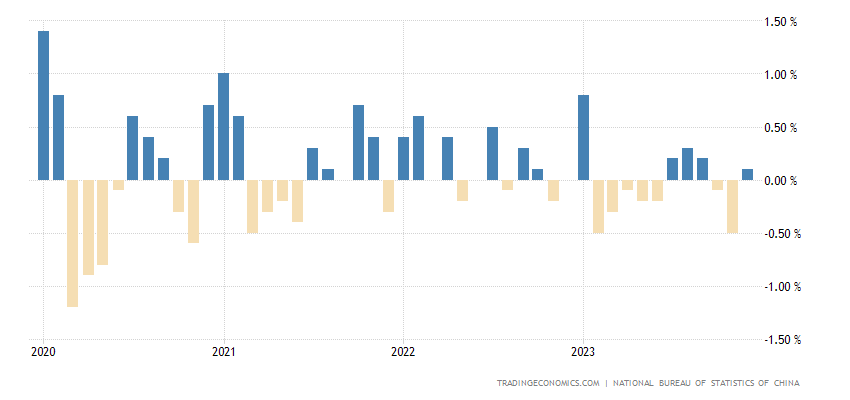

Aside from the moribund stock market, China’s most visible sign of economic decay has been the lack of inflation and the emergence of outright deflation in the Chinese economy.

Indeed, deflation has been a persistent theme within China since 2020.

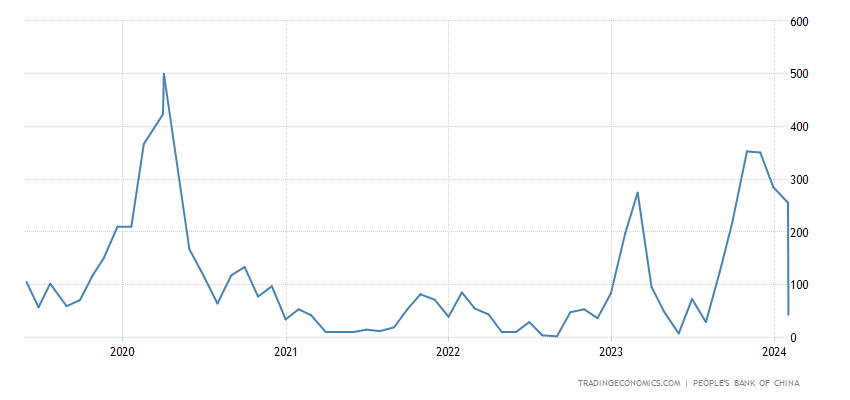

What makes this deflation particularly noteworthy is that is happening despite Beijing’s steady infusion of more and more money into the economy, with both the M2 money supply and the M3 money supply showing steady growth at a time when deflation is stalking the Chinese economy.

In fact, China has recently injected near record levels of liquidity into their financial system, with no apparent inflationary impact in consumer prices.

Despite this, Chinese loan growth rates have fallen in recent months.

As a percentage of total loans, the growth rate has fallen dramatically throughout 2023

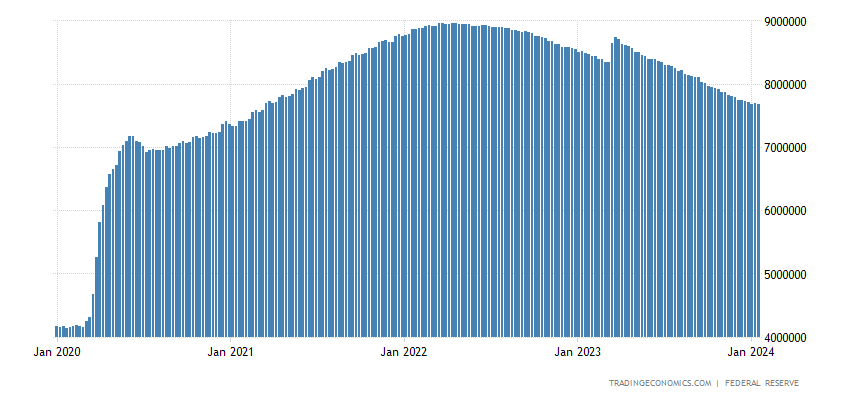

Despite the poor performance in loan originations, China has been pursuing a financial strategy distinctly contrary to what the Federal Reserve is pursuing here in the United States. China’s central bank has, unlike the Federal Reserve, greatly expanded its balance sheet in 2023.

The Federal Reserve, on the other hand, has focused on shrinking its balance sheet.

The People’s Bank of China is deliberately pursuing policies which prevailing wisdom, such as it is, says are calibrated to produce runaway inflation—and are failing to produce anything but deflation.

That can only mean economic collapse is well under way in China. When even inflationary central bank policies cannot produce inflation, the central bank dare not even think about restraining such policies, as that would produce even greater deflation. The PBOC is quite literally trapped in a cycle of permanent quantitative easing—and has arrived there well before the Federal Reserve finds itself compelled to follow suit.

The Fed’s policies are proving marginally superior to those of its Chinese counterpart, but only just, and only because the PBOC has been more explicitly manipulative.

The Federal Reserve may have just won the central banking race to the bottom by virtue of the PBOC getting there first.

One major net effect of China’s unfolding economic calamity: capital has been increasingly fleeing China, producing a steady net outflow of investment capital.

Note that capital flight has been a staple of the Chinese economy since the early 2000s. Again, the contrastng capital flows for the United States over the same period is nothing short of miraculous for the US.

It is relatively easily to keep an economy seemingly afloat even when most of the fundamentals are have a negative outlook provided one has a net inflow of capital. As long as there is new money flowing into an economy, even when it is in a recession it will not produce a runaway collapse such as what we have taking place in China.

Despite the numerous flaws and weaknesses in the US economy, it is at least still able to attract net inflows of investment capital. China has never seen sustained net inflows of investment, and has always seen rising capital flight. When Chinese investors want to invest anywhere but in China, there is no possibility for sustained economic growth of any kind.

There is literally no part of the Chinese economy that is doing well at present. Investment capital is fleeing the country, manufacturing is not expanding, with the result that exports are declining—and will decline further as increased shipping rates on goods from China thanks to Iran-backed Houthi missile mischief in the Red Sea.

As much as Beijing wishes to avoid yet another round of government intervention into the economy, it has steadily been ramping up more and more stimulus measures—only the measures are not stimulating. The economy has been absolutely resistant to any sort of inflation or showing any of the usual signs of economic expansion even as Beijing has unveiled ever increasing amounts of stimulus.

The simple truth is that China has never recovered from the economic lunacy of Zero COVID. Between Zero COVID and the unraveling of China’s property markets due to Xi’s “Three Red Lines” diktat from 2020, literally all the economic supports in China have been knocked out. Manufacturing has been disrupted, construction has been disrupted, real estate has been disrupted—and nothing is left to resuscitate the economy.

The reality is exactly what was predictable in 2022, during the height of Xi Jinping’s Zero COVID paranoia: Xi would lead China right over the economic cliff.

In 2024, the probabilities are growing almost daily that the world will see just how steep that cliff is for China, and just how far it will fall before it hits bottom.

Great article as always. Thanks for your excellent insight.

Some thoughts:

-many unemployed youth… will it be a deciding factor for Xi taking Taiwan?

-Xi economy is toast… will it also push him into taking Taiwan ?

-we have China government on its knees soon. If anti China policies continue… can it help topple Xi/CCP?

-sadly I heard ridiculous rumours on the internet television about how China could be bailed out? Lol. Omg on that one. Crazy

-I also heard China woes may be related to a possible Trump win in 2024? Lol. On the graphs…..As Trump polls rise… China numbers sink. Lol.

China has been anti-Trump and has been behind the scenes undermining him. But they didn’t realize how their meddling world policies would contribute to their poor economic outlook? Will they finally admit world peace, financial stability, etc., helps them too?

They are pushing RFK Jr on Tik Tok like crazy. Obviously they see him as another climate change lunatic democrat that they can manipulate to their benefit. If everyone continues the green agenda to benefit China then upheaval continues. Not sure if China calculated this and if they did… they don’t care? In the long run if they control the worlds energy needs with batteries/ solar … they win! I don’t know what they are going to do.

Apparently there is an old Chinese forecast/folk tale that Xi will be the last leader. Omg I hope it’s true. Lol. Hopefully the good people of China make major changes in their government one day.

Great data, and you point out several aspects of the situation that other writers have not, such as the effect of shipping costs on China. I think China’s developing nightmare will be one of the most fascinating and important events of the coming year. Think of the geopolitical implications! China will become the textbook case for why command economies cannot work, or, as you’ve wisely written, “you can’t push a string”. Other countries will back off from top-down economic strategies. The Belt and Road Initiative could completely unravel, maybe even backfire in some countries. Iran will not have an economically-strong silent backer. And if China falls off a cliff, that could be a saving grace for the US economy, as investment comes to us instead of to China.

Look at this article from yesterday’s Epoch Times: https://www.theepochtimes.com/opinion/will-the-ccp-save-chinas-stock-market-5579541?utm_source=ref_share&utm_campaign=copy

Part of me wants to laugh. The CCP wants to REQUIRE state-owned firms to bring finds held overseas and put them into the Chinese stock market! Are they nuts? Money will go down a bottomless hole, and the heads of these firms will lose pretty much everything. Does the CCP not realize what kind of revolt that could provoke? What kind of financial chaos?

I don’t wish any suffering on the Chinese people, but wow, you have not overstated your case, Peter. This really is going to be bad!