Goldman's China Growth Dream is All Wrong

China Isn’t Growing, No Matter What The Vampire Squid Claims

According to the “experts” at Goldman Sachs, China is poised to undergo improved economic growth in 2026, more than is currently forecast by either the IMF or the World Bank.

China’s real export growth is now expected to grow by 5-6% annually for the next few years, up from a previous forecast of 2-3%, as Chinese goods gain global market share, Goldman Sachs Research economists Andrew Tilton and Hui Shan write in the team’s report.

The team nudged its forecast for China’s 2025 real GDP growth from 4.9% to 5.0%, and with even bigger increases for forecasts for the next two years, on the view that stronger exports will drive overall economic expansion. Goldman Sachs Research increased its real GDP forecast for 2026 from 4.3% to 4.8% and for 2027 from 4.0% to 4.7%. This puts our economists’ Chinese growth forecasts for 2026 and 2027 well above the consensus estimate as tracked by Bloomberg, and above forecasts from the International Monetary Fund.

I have not written about China in quite some time. Partly this has been a reflection of constraints on my research time, but it is also a reflection of the sobering reality that not much is changing in the Middle Kingdom at the moment: the politics are still authoritarian, Xi Jinping is still a Mao Zedong wannabe, and the economy is still spiraling into deflation. There are only so many ways to restate the same narrative arc without becoming hackneyed and cliche.

However, when an investment bank as hefty as Goldman Sachs releases an optimistic growth projection for China’s economy, it is time to review China’s economic data, to see if the Vampire Squid’s1 projection has merit.

Spoiler alert: it doesn’t!

The problem with Goldman Sachs’ projections for China is not merely the levels of growth guesstimated. The problem is the presumption that there will be actual growth at all. Growth in China’s economy requires the reversal of every significant current economic trend in the country. Making such presumption the basis of a projection is not merely overweening optimism, it's borderline psychotic delusion. The reality of the data just does not get us there.

China Has Not Had A “GDP Growth” Narrative For Years

Straight away, Goldman Sachs’ projections are remarkable because they run counter to the prevailing trend of China’s economy for more than decade.

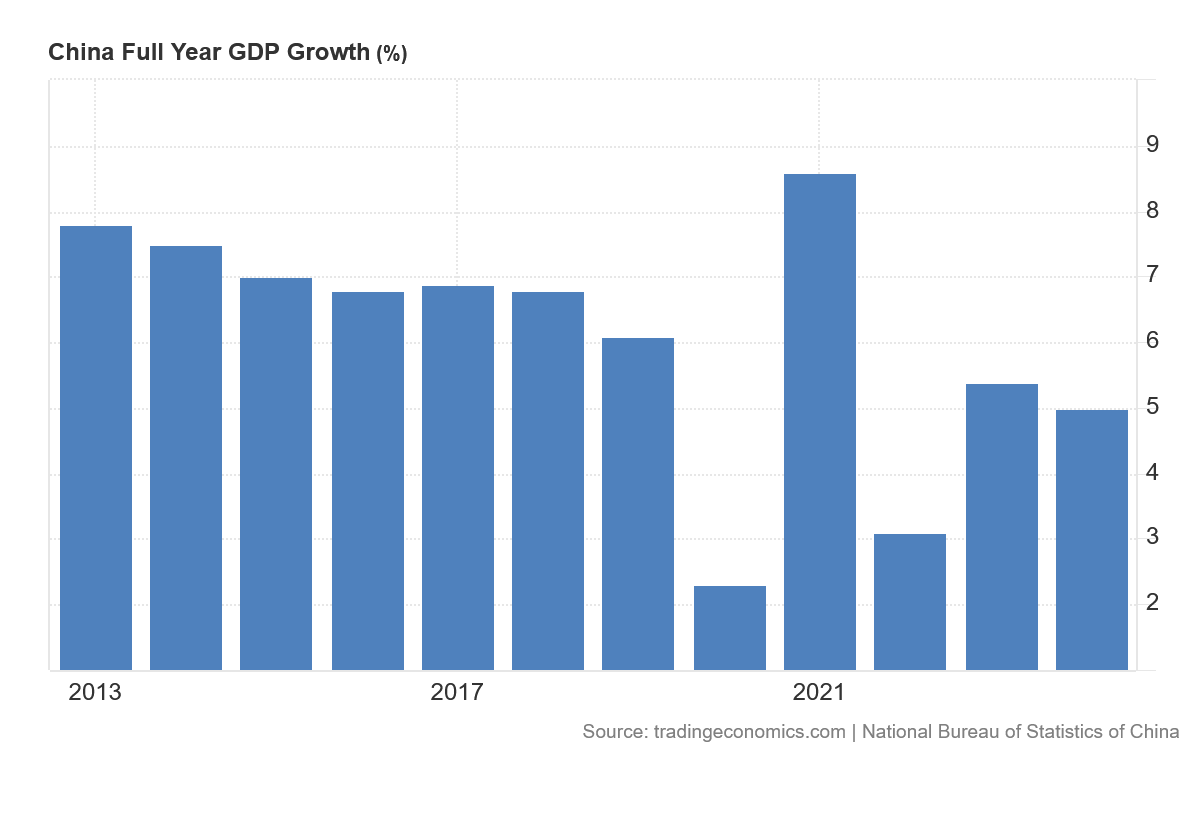

Aside from the extreme growth and contraction swings following the 2020 COVID Pandemic Panic, China’s economy has been growing by less and less each year since at least 2013.

We should note that, regardless of how we apprehend the accuracy of China’s data, these figures come to us from China’s own National Bureau of Statistics. All the data presented here are “official” China metrics (charted by Trading Economics for convenience). The claim that China’s economic growth has been slowing since at least 2013 is what China itself is saying about its economy.

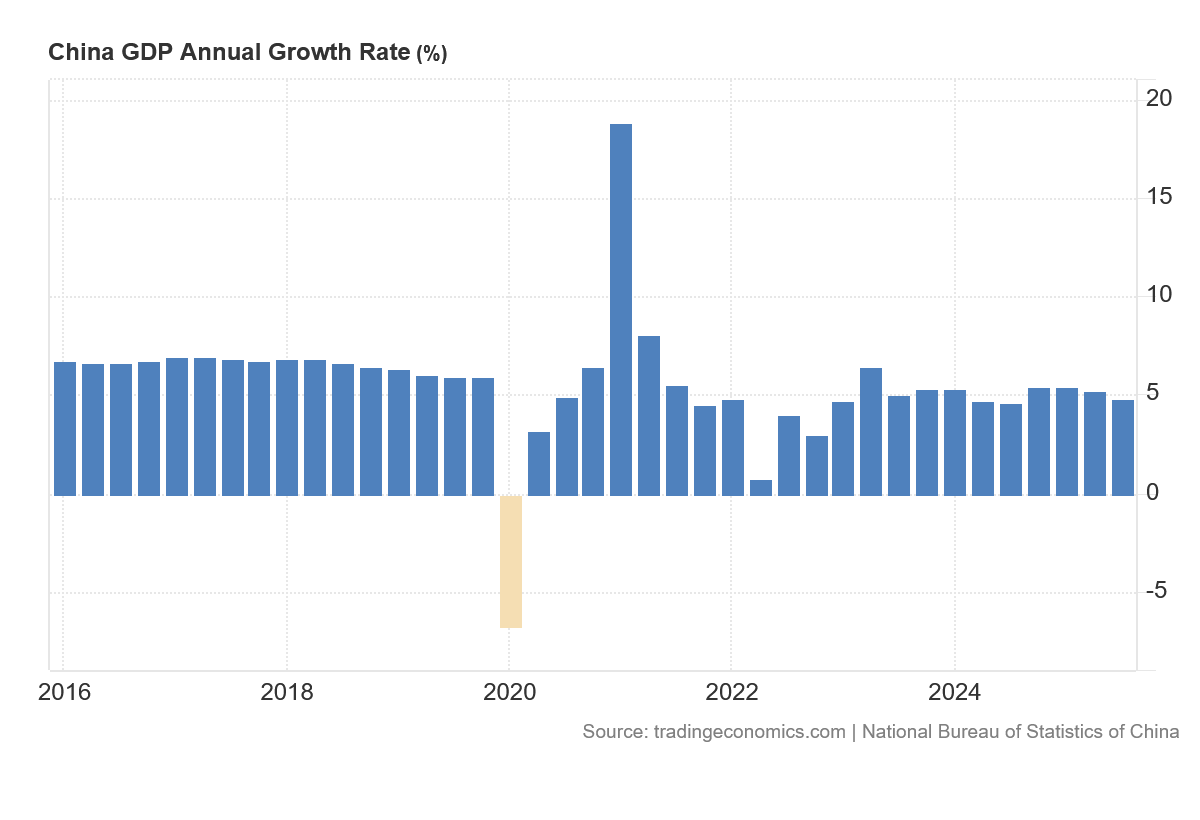

Even if we look at the quarterly GDP growth metrics, we still have a downward trend in economic growth, except during the disruptive period of the Pandemic Panic.

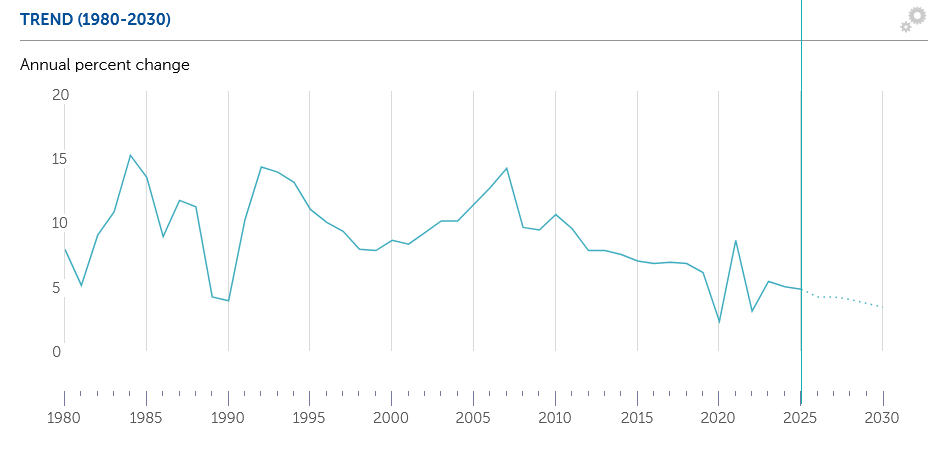

According to the International Monetary Fund, China’s economic growth rate peaked in 2007, with real GDP growing by 14.2%.

That China’s GDP growth has come in smaller and smaller increments is a trend not just reported by China’s NBS but confirmed by the IMF.

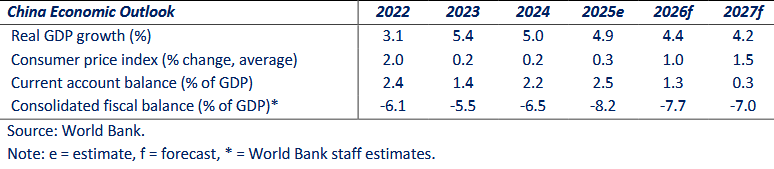

For its part, the World Bank confirms that China’s real GDP growth has been in smaller and smaller annual increments, a downward trend resuming after digesting the dislocations of the Pandemic Panic.

Two presumptively non-partisan, non-ideological institutions confirm what China itself acknowledges about its economic growth: the growth rate has been trending slower and slower for years, even decades.

Goldman Sachs is predicting this trend will reverse significantly.

However, Goldman Sachs is something of an outlier with that prediction. UBS, another investment bank, is projecting even slower economic growth for 2025 and 2026.

Under the baseline, we expect China’s GDP growth to slow to 4.0% in 2025 and 3.0% in 2026, with the assumption that the US hikes tariffs on China’s exports starting in September 2025 and China would increase policy support in response. Net exports will likely still contribute positively to GDP growth in 2025, but we expect exports to fall sharply in 2026, bearing down on manufacturing capex and prices. We expect additional fiscal expansion in 2025-26 to help alleviate local government financial challenges, support infrastructure investment, and help to stabilize the property market. Nevertheless, we expect CPI inflation to weaken to 0.1% in 2025 and -0.2% in 2026 along with a weaker growth.

Goldman Sachs is one of the few investment banks seeing the required patterns necessary for a trend reversal to occur.

To be sure, trend reversals do happen. In economics, where events tend to follow cyclical patterns, trend reversals are almost guaranteed—eventually.

The question is whether the overall trend are leading to a trend reversal and more economic growth, or even a momentary surge for a quarter or two of economic growth.

Certainly within the overall macro data reported by China, a case for trend reversal is difficult—even impossible—to sustain.

Per Capita GDP Growth Still Lags

One of the principal challenges facing China is not merely a question of economic growth overall, but how to raise China’s per capita GDP to align with the levels found in the United States in Europe.

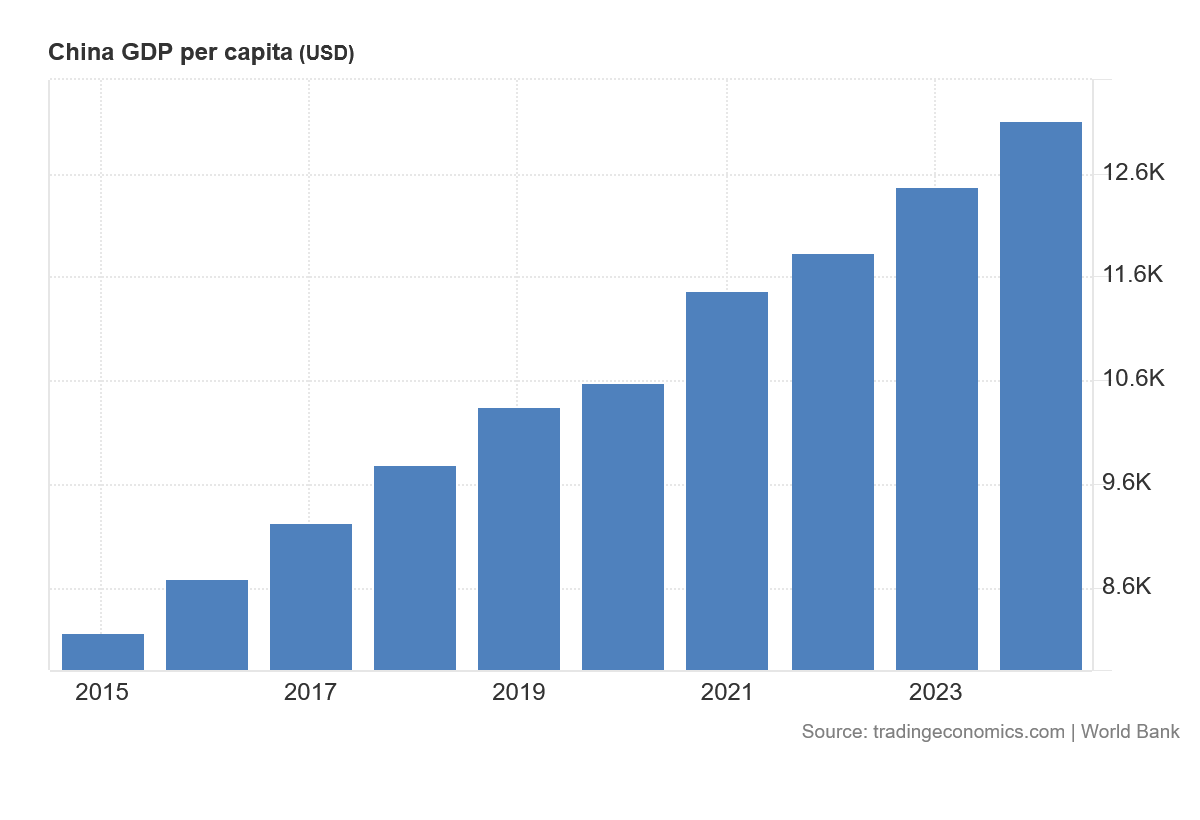

Looked at in isolation, China’s Per Capita GDP has risen steadily over the past decade.

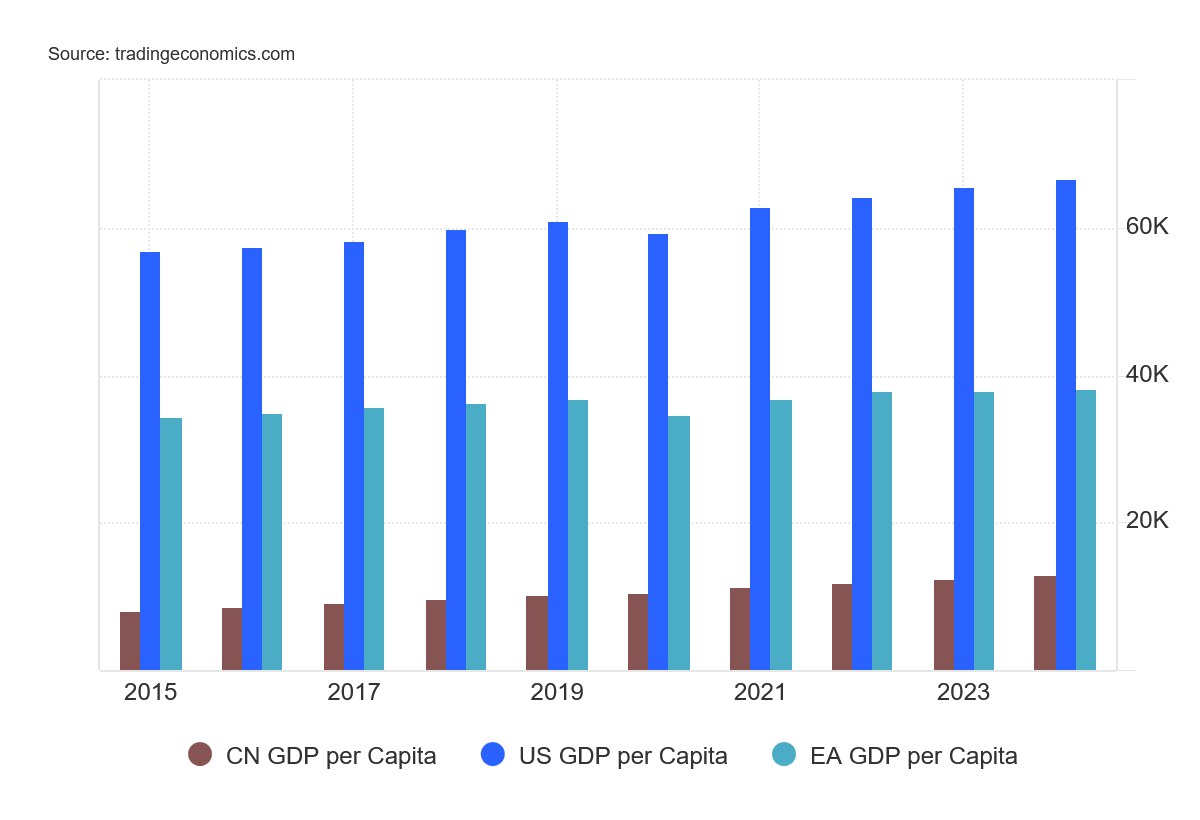

However, China’s Per Capita GDP compared to that of the United States and the European Union is quickly seen as far less impressive.

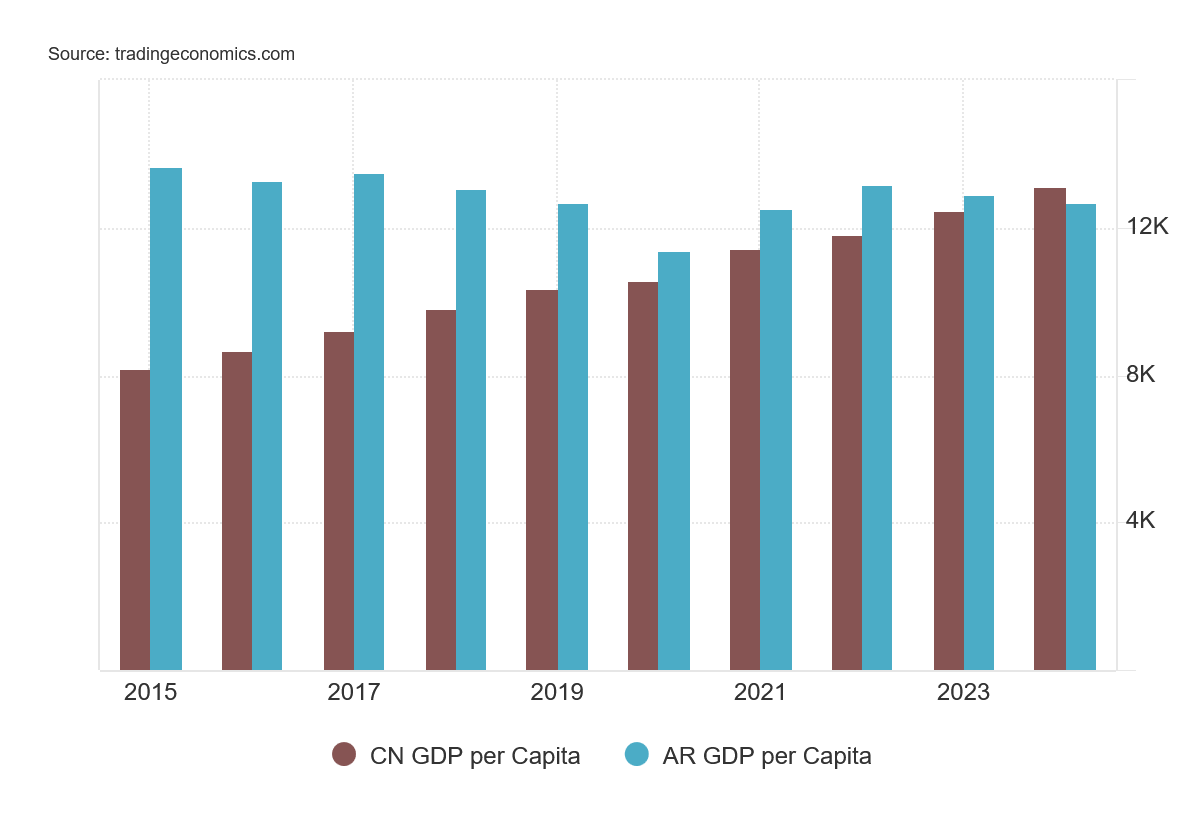

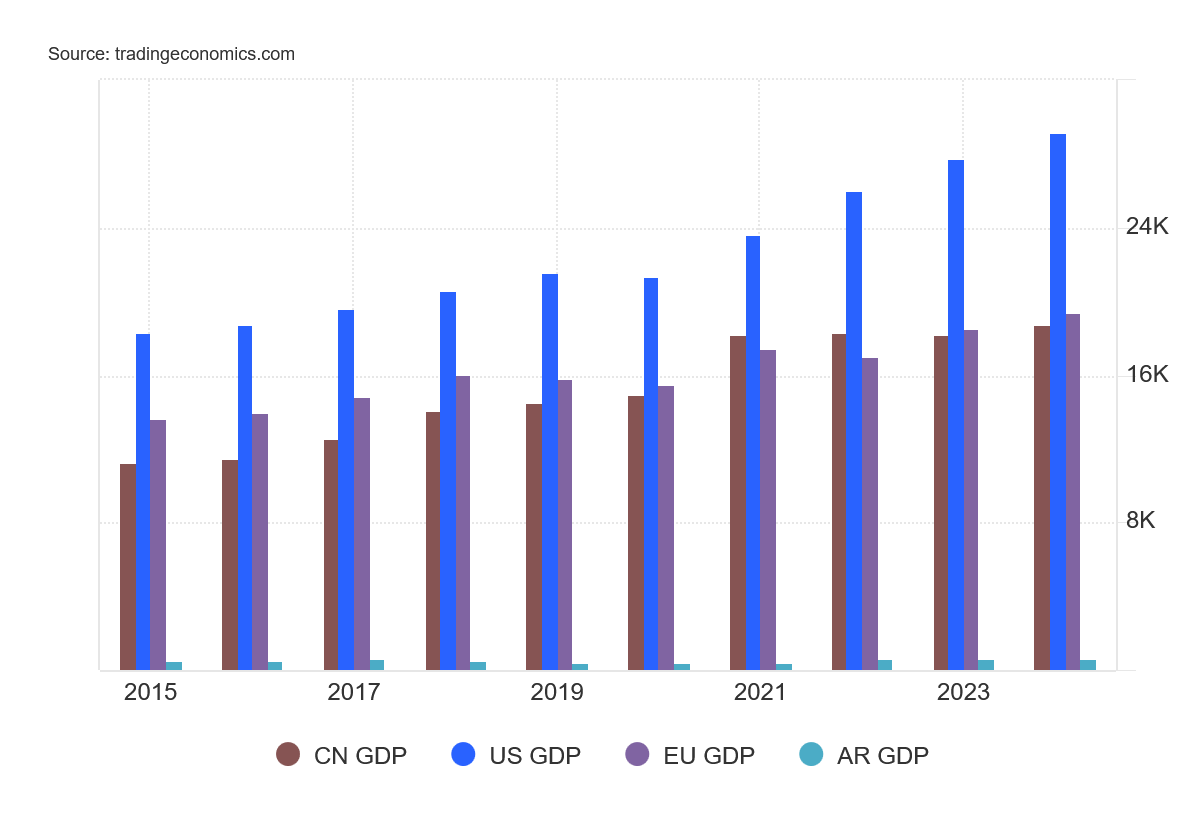

On a per capita basis, China’s economic heft compares more realistically to an economy such as Argentina—which, despite decades of economic turmoil, still is in rough parity with China.

China’s large population is how its aggregate GDP stands more in comparison to that of the US rather than Argentina.

China’s economy, per capita, is more like economies which are a fraction of its aggregate size.

Given China’s population, if Beijing were successful in raising China’s per capita GDP to even close to that of the EU or the United States, it would have the largest aggregate GDP by at least a couple orders of magnitude.

Whither Consumption?

The significance of the per capita GDP figures can be summed up in one word: consumption.

One of Beijing’s explicit policy objectives coming out of the recently-concluded annual Central Economic Work Conference was boosting consumption.

In terms of tasks of next year’s economic work, the meeting said domestic demand will remain as a focus in building a robust domestic market.

Special initiatives should be advanced to boost consumption, and the supply of high-quality consumer goods and services should be expanded. Unreasonable restrictions in the consumption sector should be removed, and the potential of service consumption should be unlocked.

Consumption is relevant to China’s future economic prospects both for economic and geopolitical reasons.

Consumption is important economically because individual household spending is variably understood as either a proxy for economic growth or an engine of it2.

Consumption is geopolitically important for China because other nations are becoming more and more resistant to the idea of China expanding its exported output into their markets—frequently at the expense of their own domestic manufacture.

Analysts say China’s “beggar-thy-neighbor” strategy—expanding exports at the expense of other countries’ industries—is now met with growing international backlash, prompting other countries to consider new tariffs and defensive trade measures.

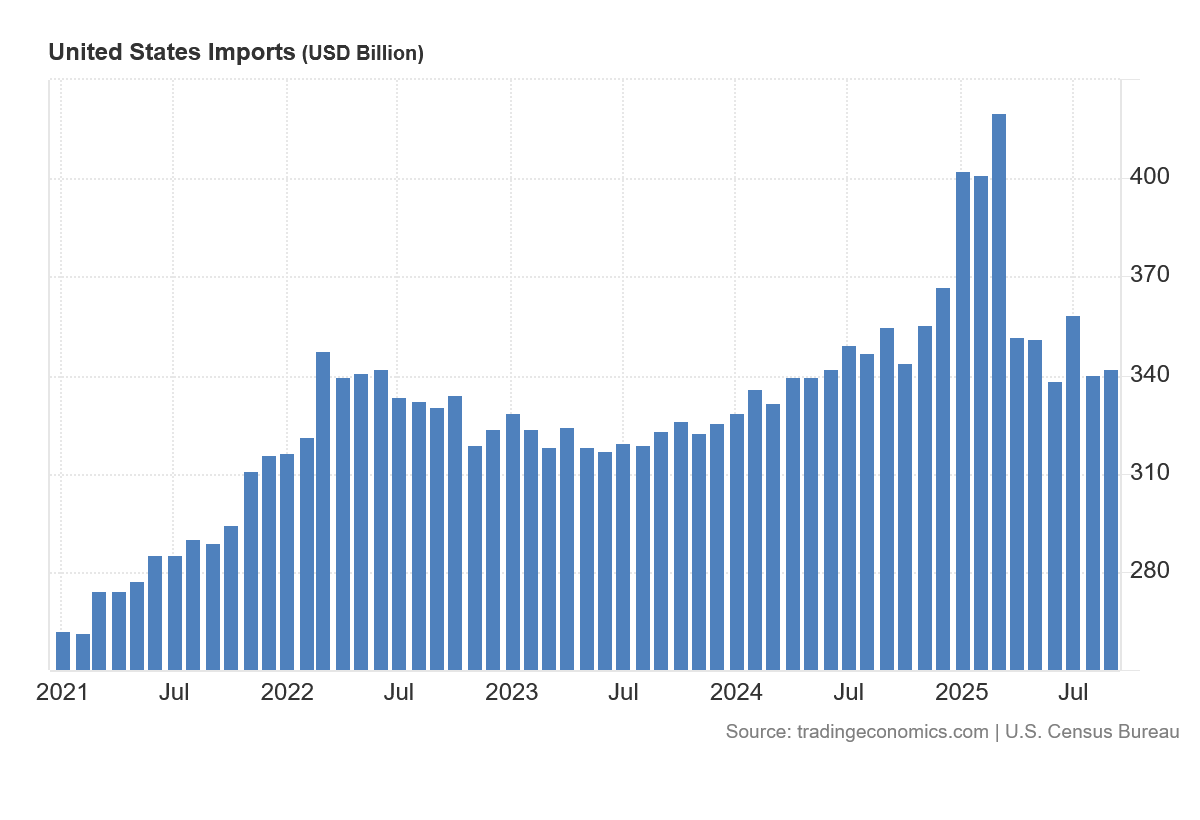

Intriguingly, the Wall Street Journal posits that the United States—Trump tariffs and all—has contributed more towards global economic growth because US consumption drives US imports, which powers economic growth elsewhere in the world. China historically has favored exports over imports, a policy that has had global economic consequences.

Pop quiz. Who has contributed more to the rest of the world’s growth this year: China or the United States?

The answer is the U.S., and it isn’t even close. Even as the U.S. rolls out tariffs, its imports are up 10% so far this year from a year earlier. And as China moralizes against protectionism, its imports are down 3%, in dollar terms.

In order to satisfy other countries’ concern over the impact of China’s exports on their own economies, China needs to boost domestic consumption, and absorb more of its own economic output at home.

While China has committed to doing that, it unavoidably labors under a major constraint in the form of low per capita GDP. Simply put, the average Chinese household lacks the necessary resources to significantly expand spending and consumption.

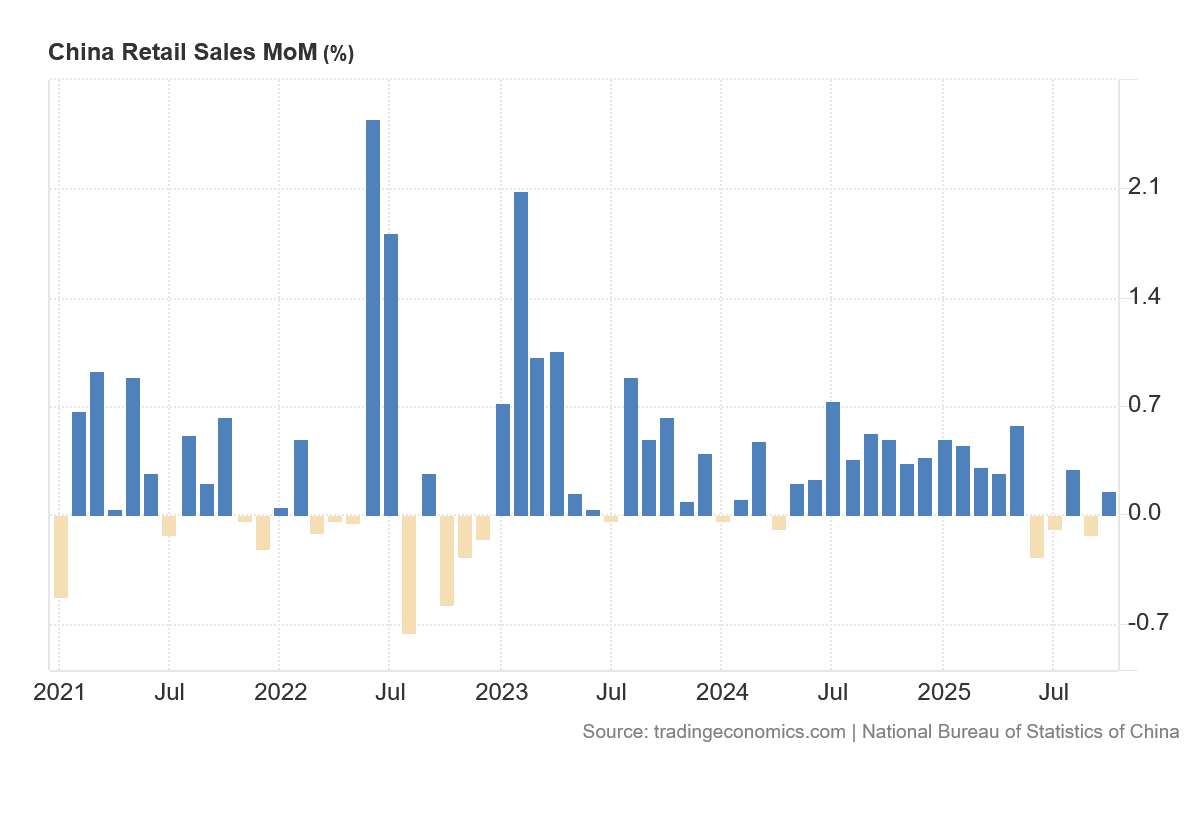

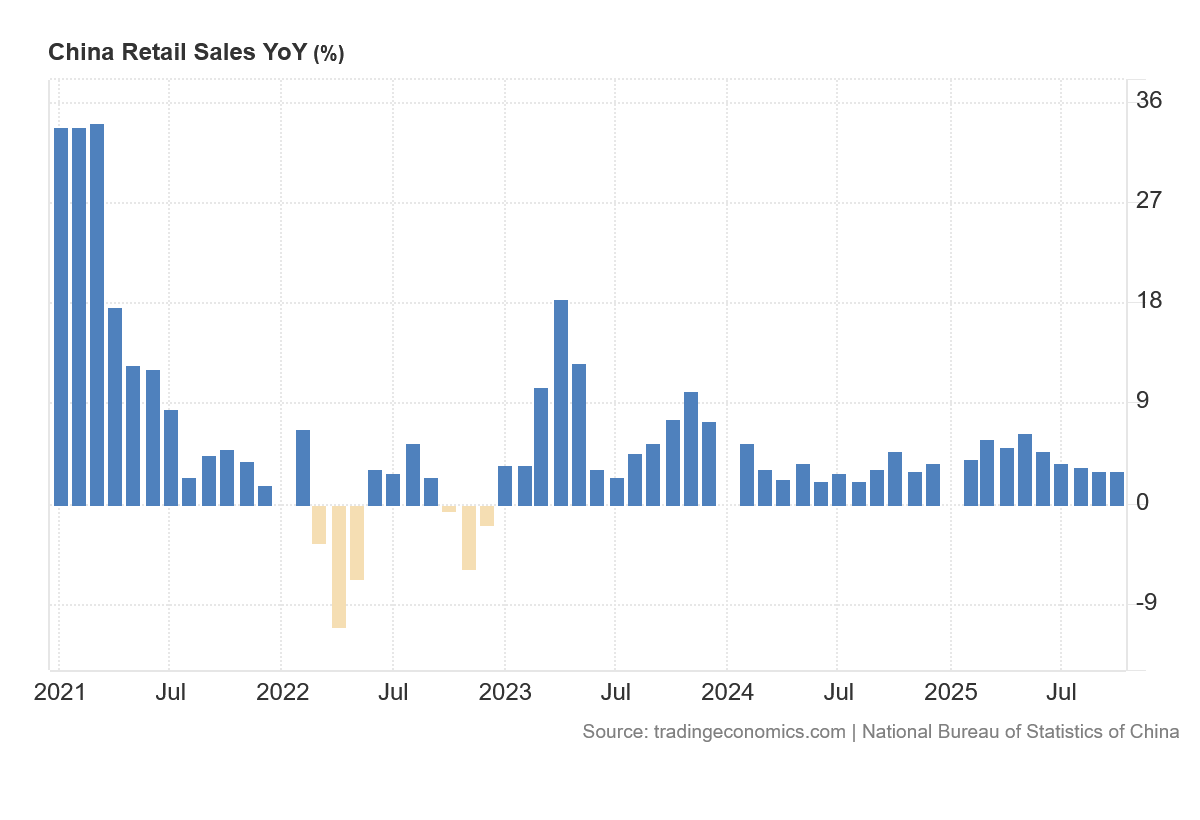

This is made immediately obvious by the slowing of retail sales growth month on month.

Nor does the assessment shift much when we look at retail sales growth year on year.

Except for a burst of sales growth during the dislocations immediately following the COVID Pandemic Panic, China has not succeeded in engineering a significant increase in retail sales. China’s households are not increasing their spending relative to overall economic growth, and the per capita GDP figures tell why: they don’t have much in the way of resources with which to spend. Chinese households certainly do not have the resources to drive spending that are found among US and European households.

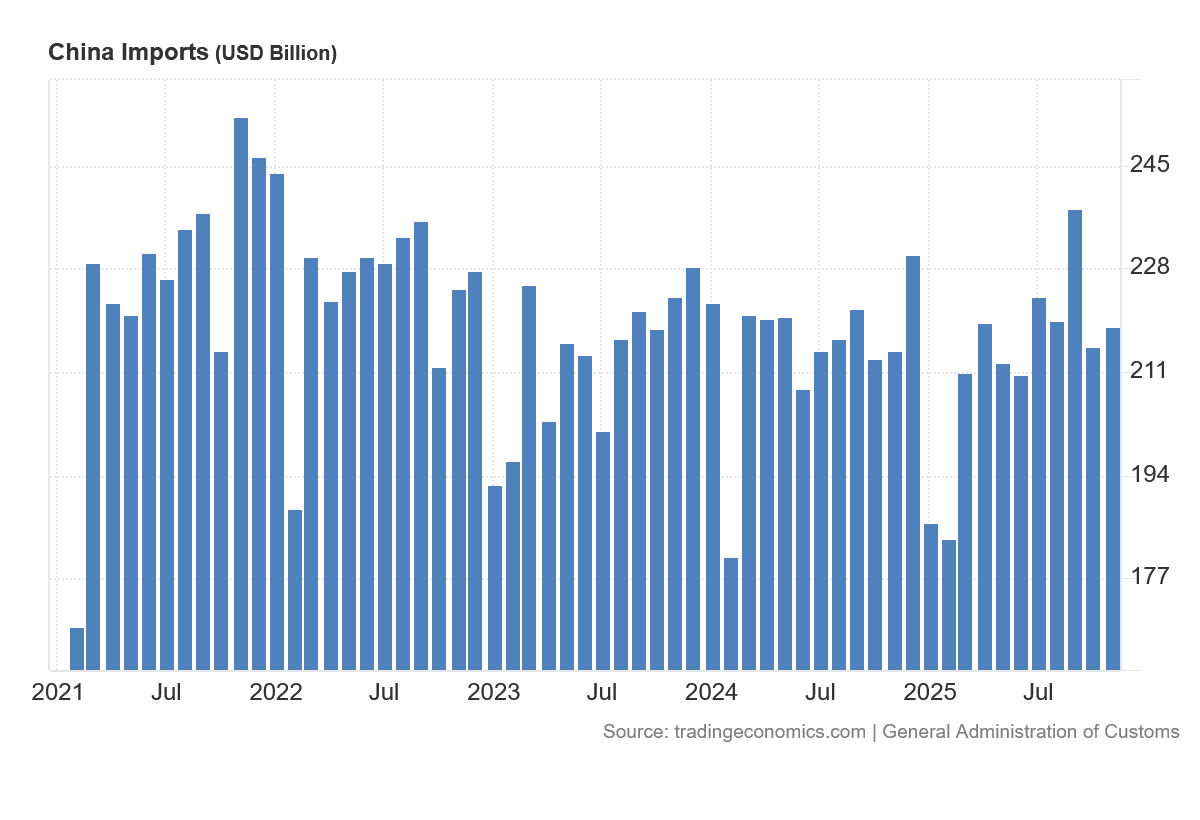

This constraint is confirmed by China’s lack of import growth.

Consumption is a key driver of imports, for the obvious reason that whatever goods a nation desires but does not produce (or does not produce in sufficient quantity) must be imported.

For comparison, consumption growth in the United States since 2021 is easily reflected by growth in US imports.

In order for China to meaningfully increase consumption as a portion of overall GDP, the per capita GDP must rise. Without such an increase, China’s capacity to leverage consumption as an engine of economic growth is constrained.

Whither Exports?

Absent consumption growth, the only other avenue for an economy to expand is through exports.

For China, this presents a problem relative to future economic growth, because China’s exports have largely plateaued over the past few years.

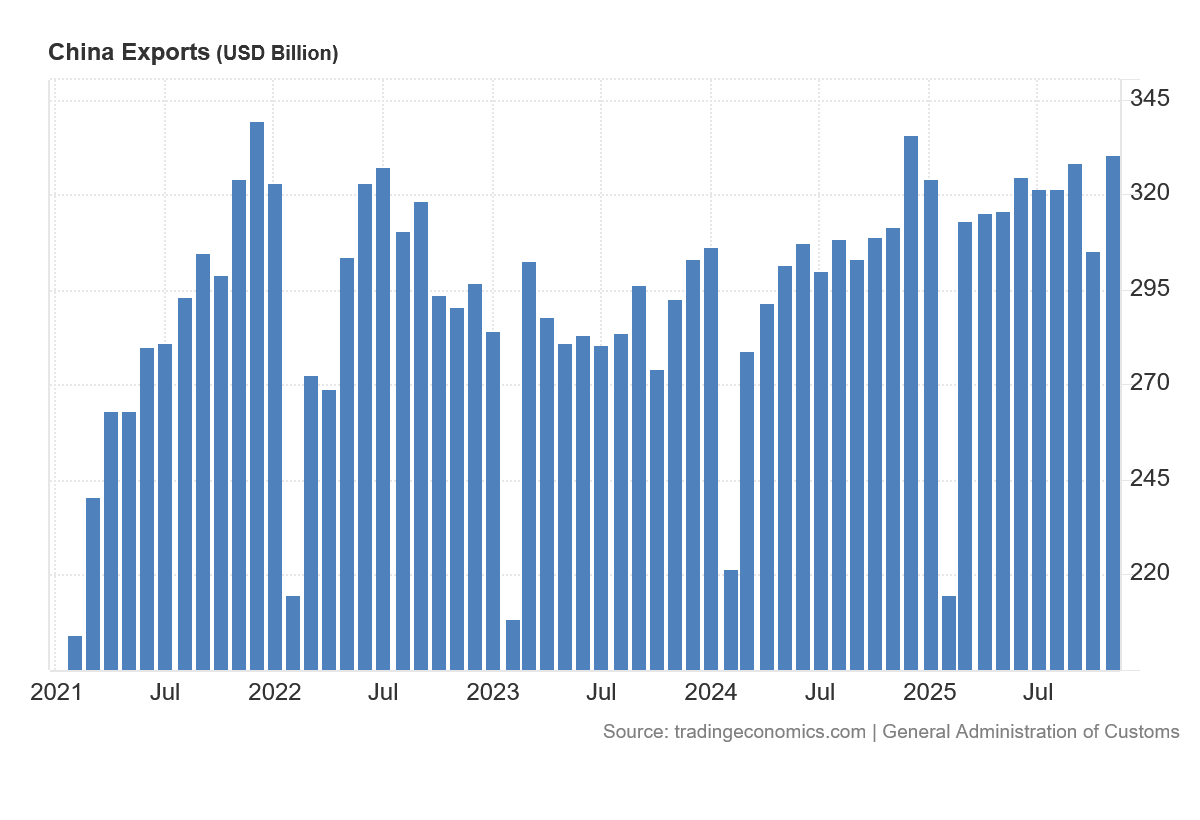

After a period of growth in 2021, China’s exports have been largely capped, and have not returned to the peak of $340Billion reached in December of 2021.

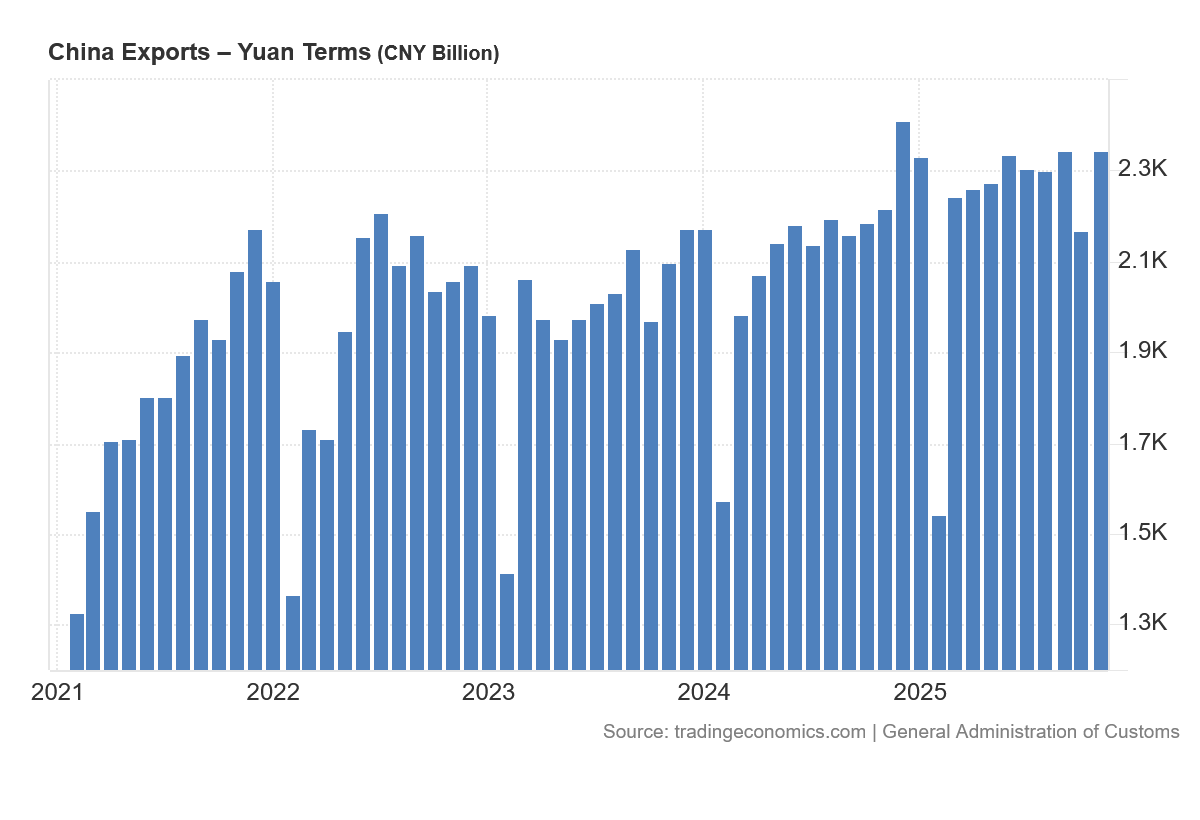

China’s export outlook does look a little better when viewed from the perspective of its domestic currency, the yuan.

However, that outlook must be tempered by the decline of the yuan against the dollar over the same time frame.

Any apparent increase in the yuan-denominated value of China’s exports in recent years is less a reflection of actual export growth and more a reflection of the yuan’s decline.

While global pushback against China’s exports is undeniably a factor, the economic impact is still a lack of export growth. Without export growth, and without consumption growth, China’s avenues for economic growth are largely blocked. One or the other has to expand, or China’s economic future is limited.

China, Inc., Is Stagnating — Update

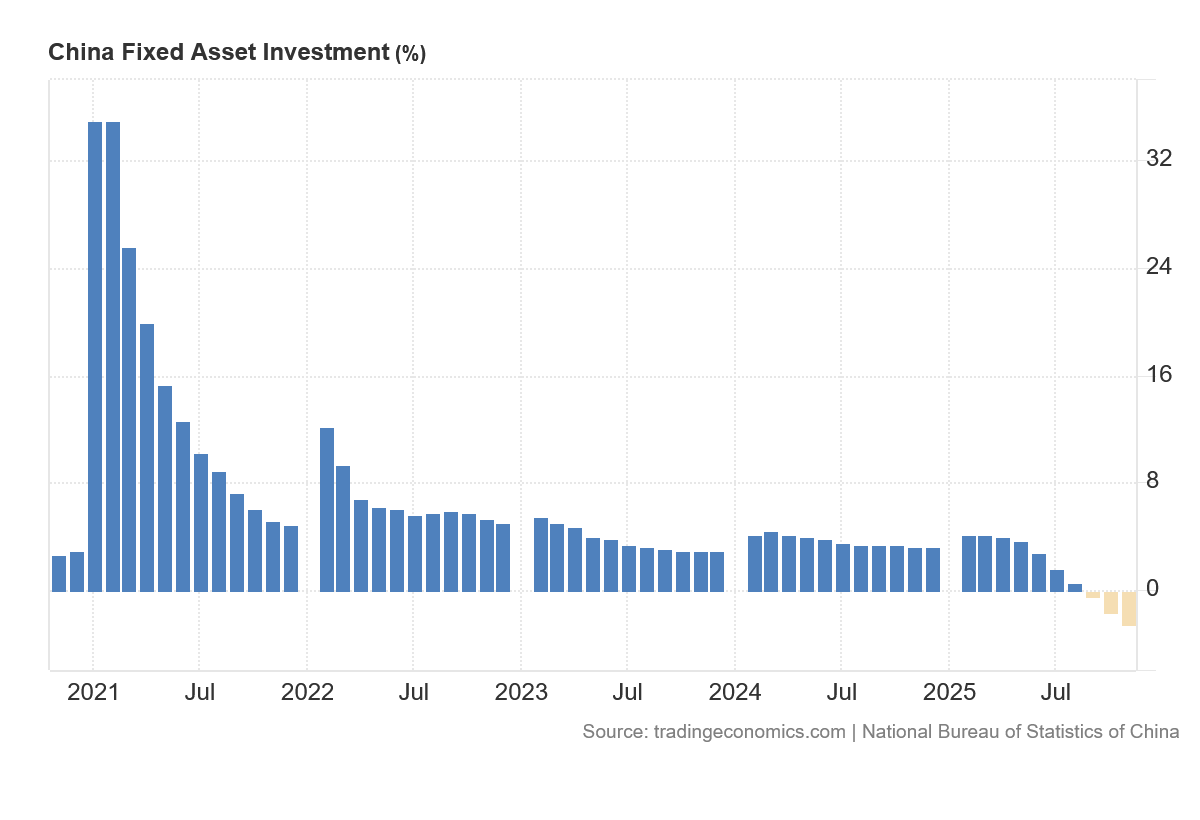

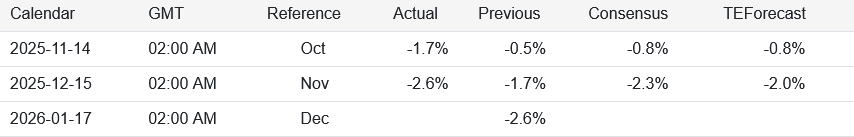

China’s latest Fixed Investment data shows that China’s economy is in fact grinding to a halt, posting a far greater than expected decline in November.

Investment for housing, public infrastructure and manufacturing fell 2.6 percent from January through November, marking another month of sharp decline in so-called fixed-asset investment, China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced on Monday. The research firm Capital Economics estimated that investment fell 11.1 percent in November from a year earlier, a second straight month of double-digit declines over 2024.

After surging in the immediate aftermath of the Pandemic Panic, China’s Fixed Asset Investment has been shrinking steadily for the past few years.

While investment growth turned negative a few months ago, November’s decline exceeded everyone’s projections.

Without investment, jobs, consumption, and overall economic growth cannot happen, especially in an economy such as China’s which is already driven primarily by exports and housing.

China is not investing in China. There is no way this can end well.

China, Inc., Is Stagnating — Starting Point

The lack of significant export growth in recent years also serves to explain another red flag within China’s economy: the decline in corporate profits.

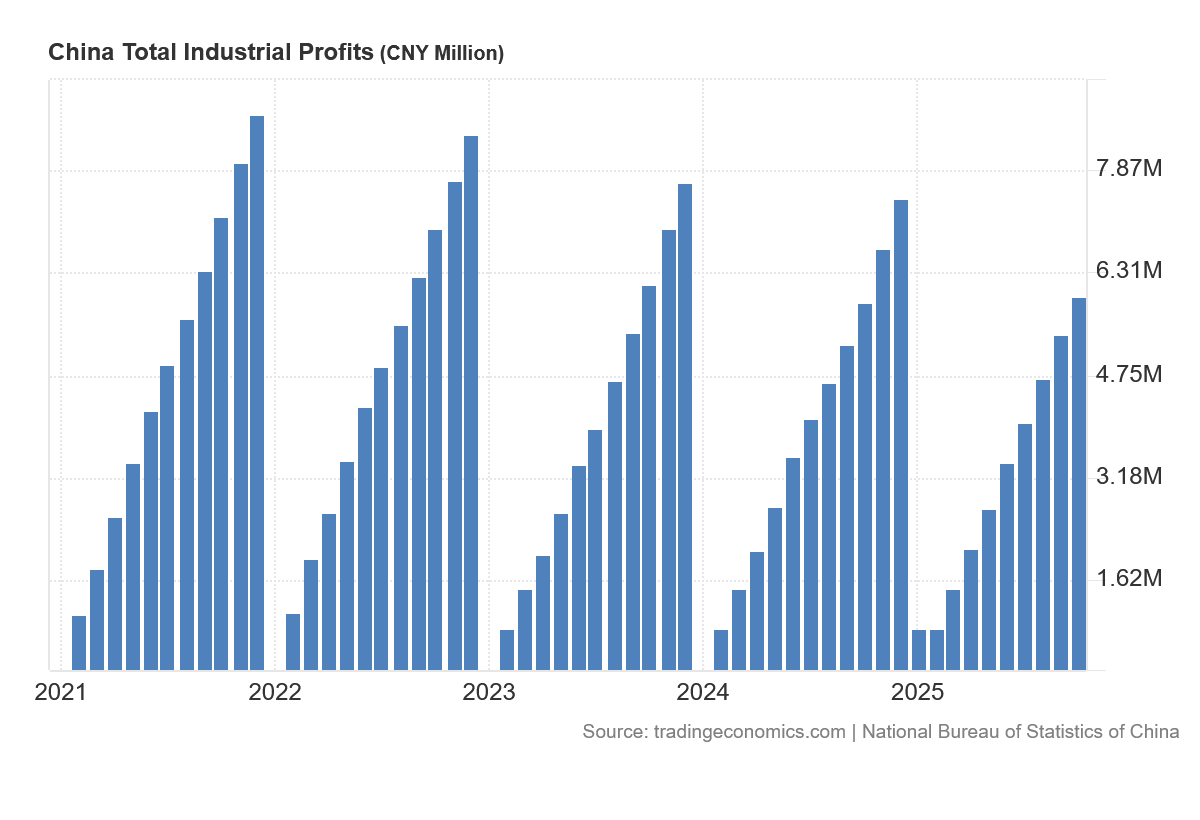

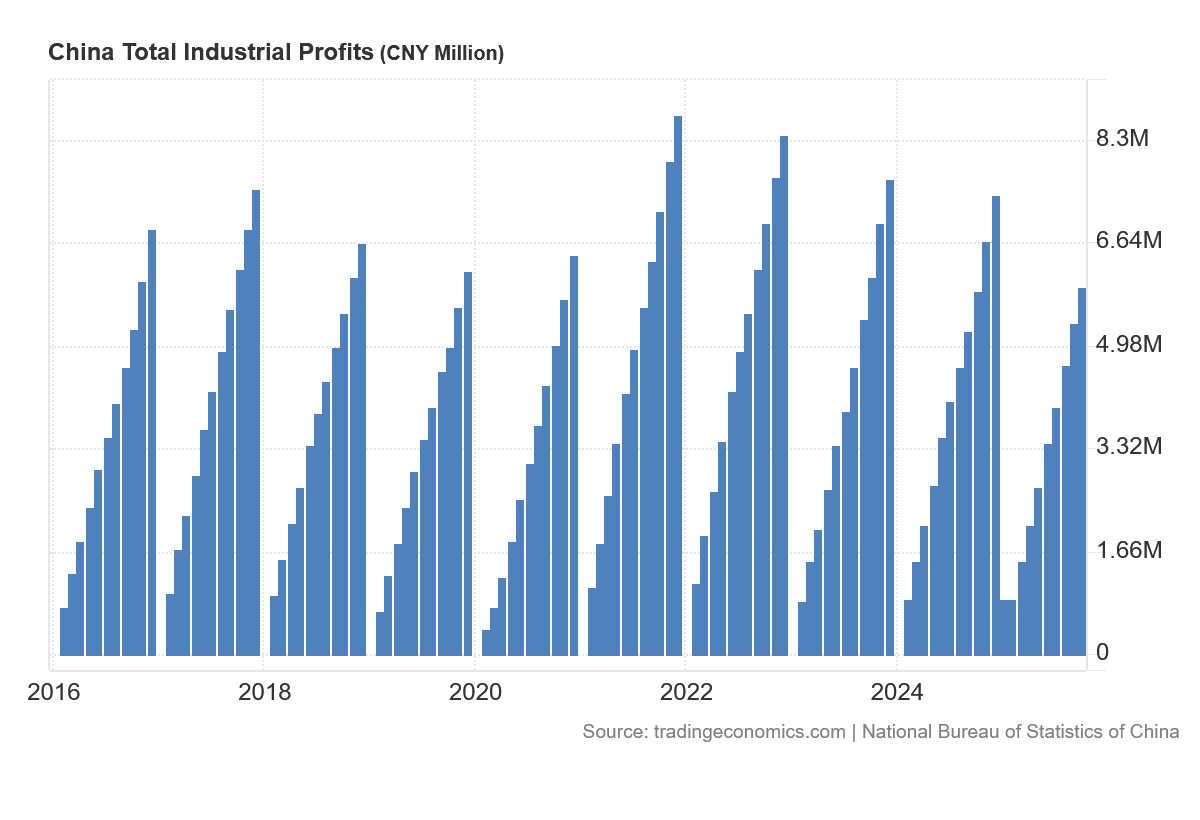

China’s companies are earning less and less each year, and have been since 2021.

Moreover, this was a trend that was disrupted by the COVID Pandemic Panic, but which was occurring prior to 2020 as well.

China’s industrial profits year to date for 2025 are less than they were in 2017, which suggests that any stimulative effect from the Pandemic Panic on industrial profits has been expended, and China’s companies are reverting to a pre-panic mean. That is not a good sign for China’s economic future.

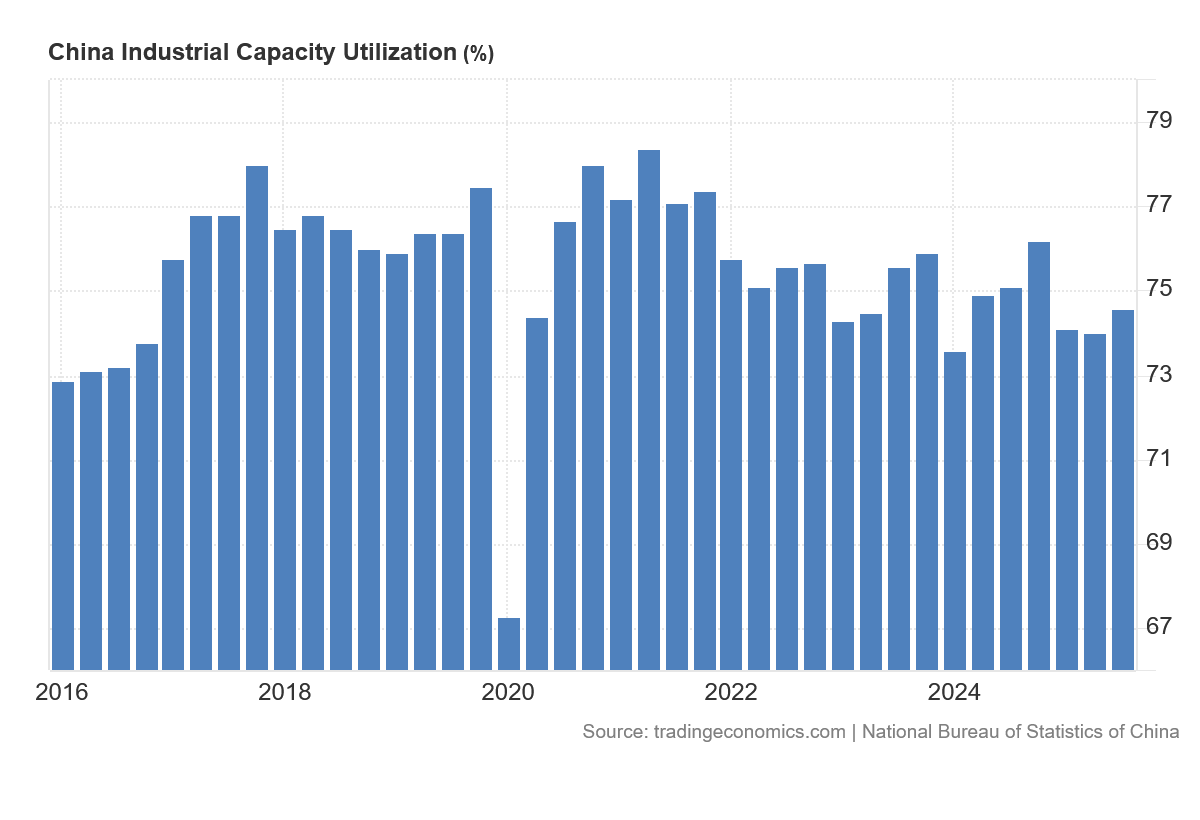

Whether there will be a quick reversal in the profit decline is problematic, because China’s industrial capacity utilization peaked in 2017, was starting to decline, peaked again in 2021, and has been declining ever since.

Whether goods are produced for export or for domestic consumption, if industrial capacity is being less and less utilized, the one thing that is certain about overall production is that it is not increasing.

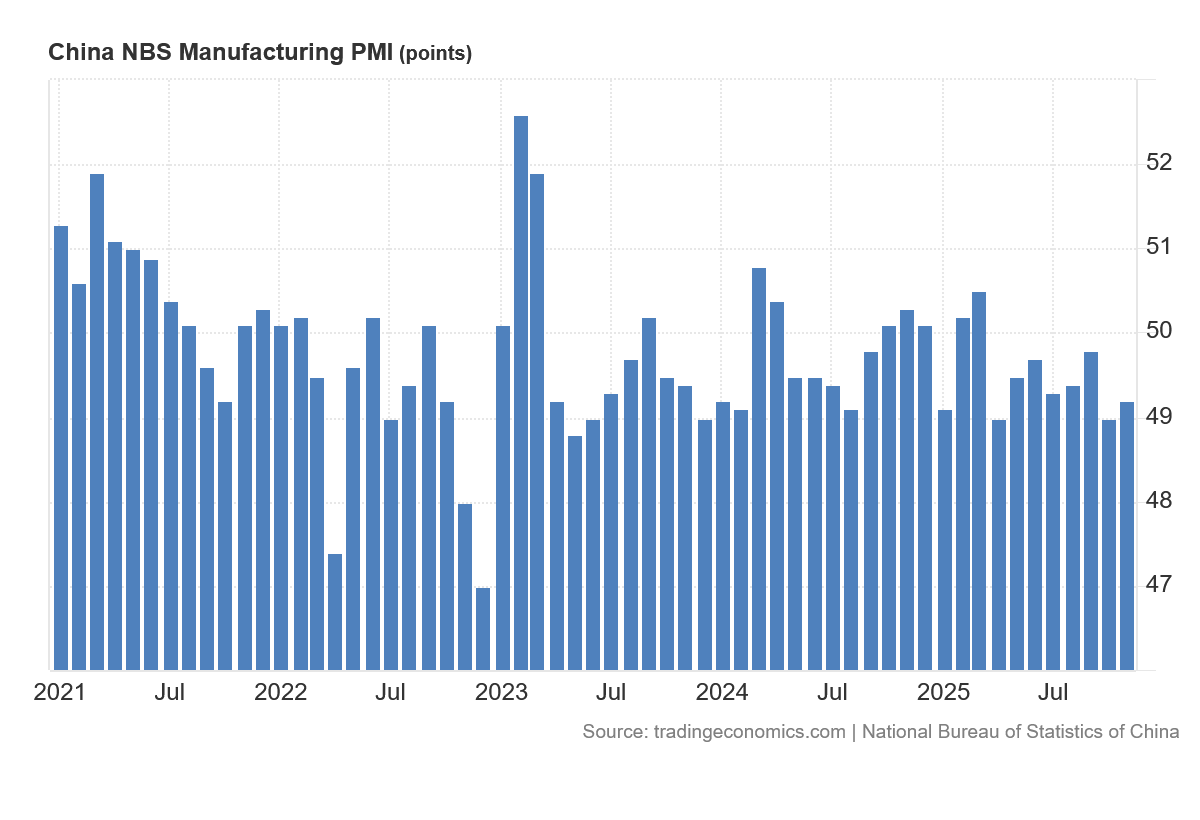

China’s reported Manufacturing PMI confirms this is the case.

Within the PMI methodology, any index value below 50 shows contraction, and any index value above 50 shows expansion. With few exceptions, China’s Manufacturing PMI has been charting contraction since mid-2022.

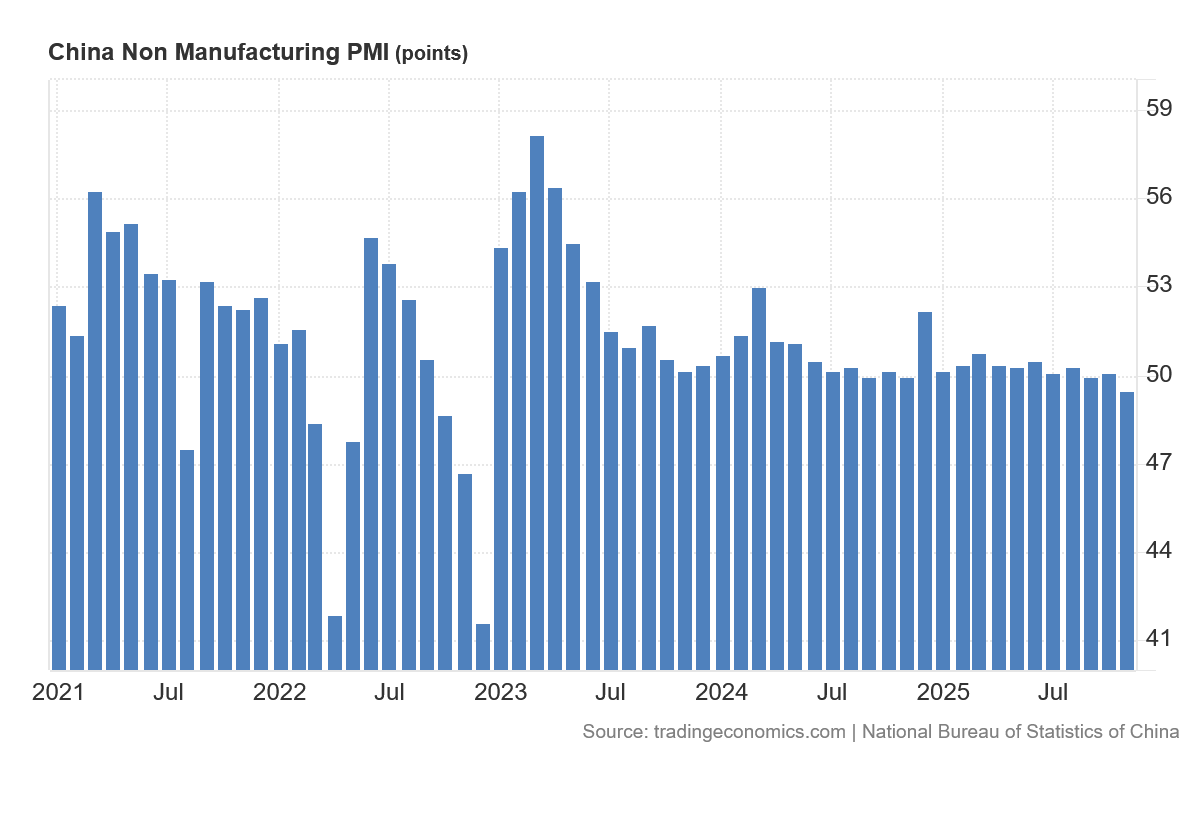

While the Non-Manufacturing PMI tells a better tale, it does not tell a much better tale, particularly in recent years.

China’s non-manufacturing (services) industries are still expanding, but only just, and in November slipped into contraction. If the trend in the Non-Manufacturing PMI continues, there will be more contraction in China’s future, not less.

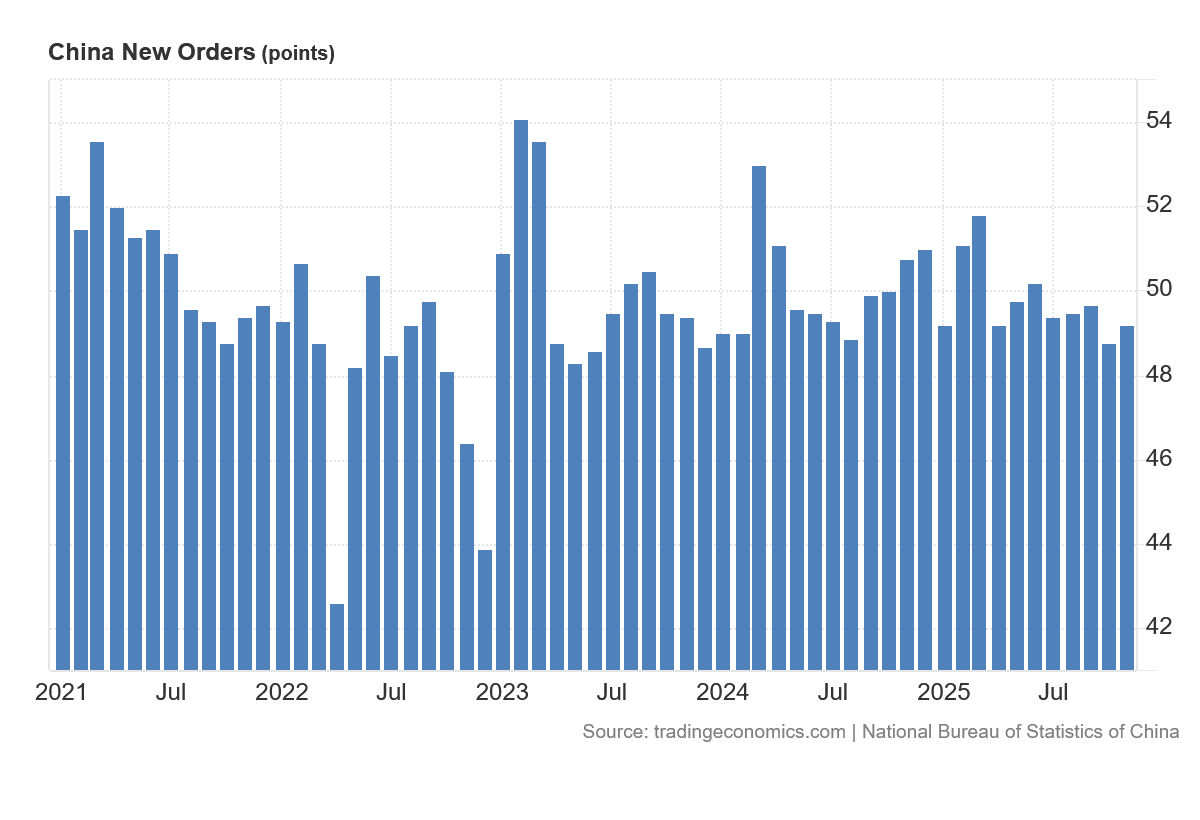

Nor is there an indication of a turnaround in manufacturing any time soon. The New Orders sub-component of the overall Manufacturing PMI has also been in contraction with regularity.

If the level of new orders are in decline, the expectation is that manufacturing overall will continue to decline—no new orders means no new business means no basis for expansion.

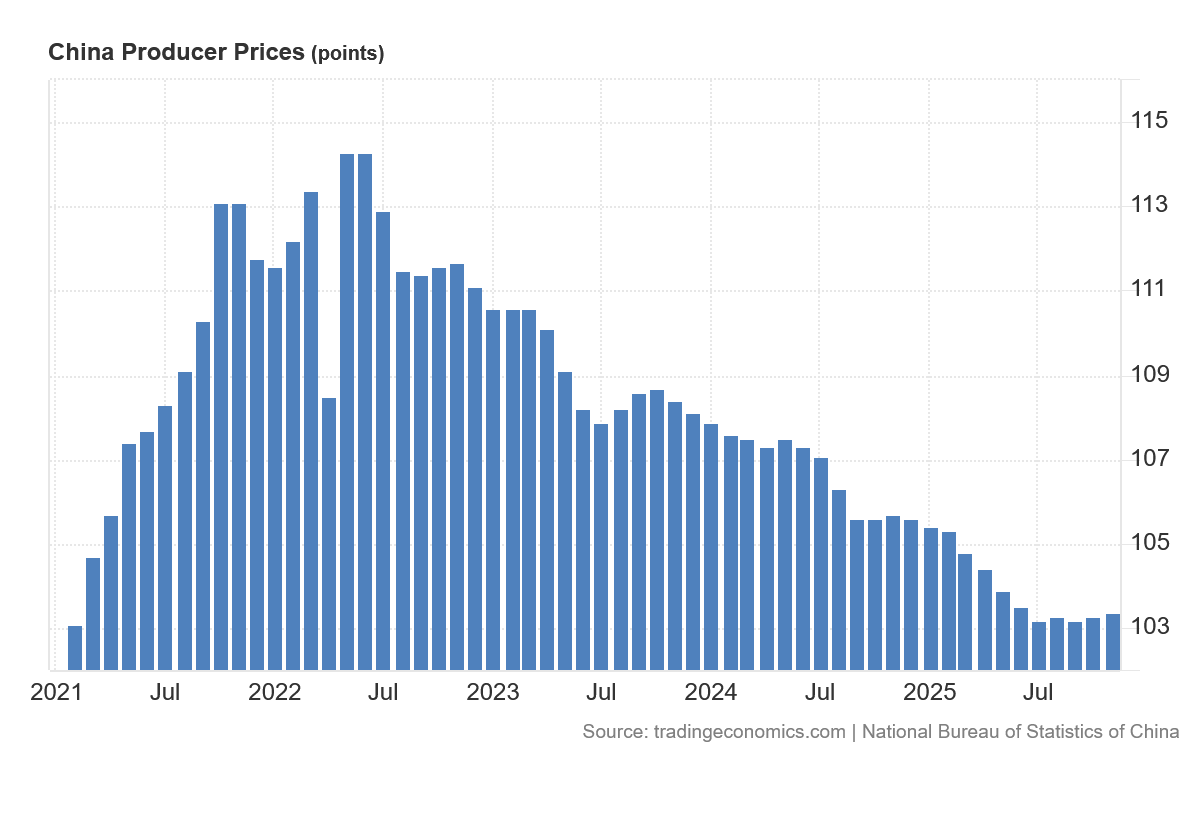

We should not be surprised, therefore, to see that China’s factory gate prices (aka producer prices) have also been in decline.

Whether due to lack of domestic demand or export demand, the reality of China’s productive enterprises is a lack of pricing pressure.

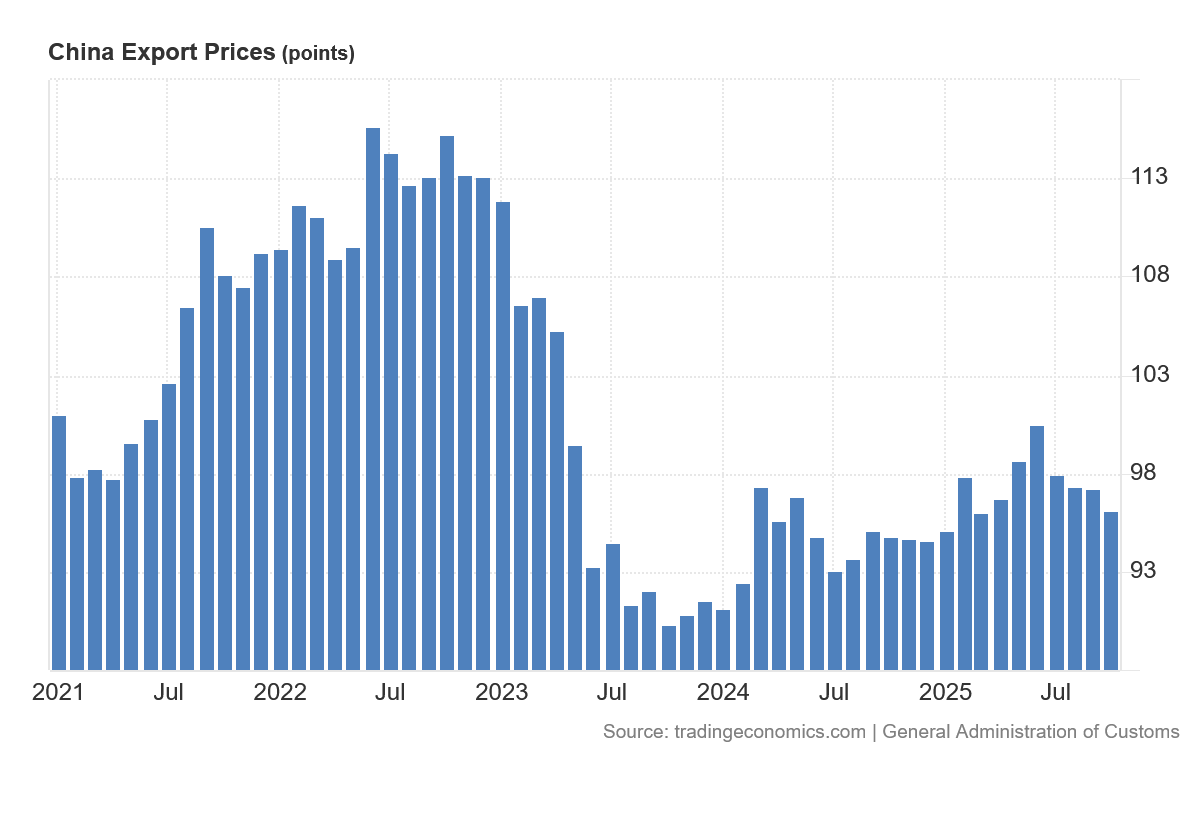

There is undeniably a lack of export demand, as China’s export prices declined precipitously in 2023.

While they have recovered somewhat from a 2024 nadir, China’s pricing power in export markets is not at all what it was in 2022.

This lack of producer and export pricing pressure is the surest sign that China has slipped into outright deflation, and appears to be stuck there.

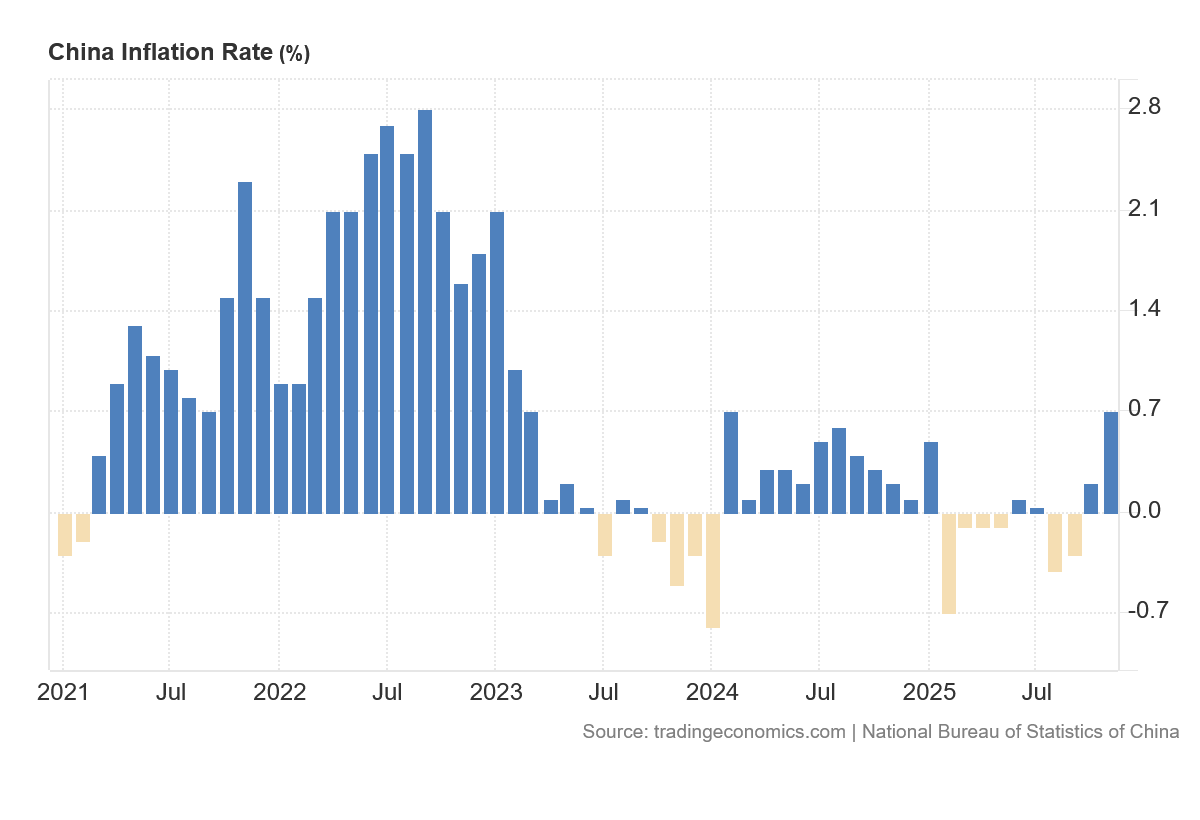

China’s lack of consumer price inflation is a stark confirmation of the stagflation/deflation diagnosis.

A lack of inflation is a lack of pricing pressure. Either there is not an increase of circulating money causing consumers to bid up prices or there is simply not the organic consumer demand. Given that China’s monetary policies have been historically lose and are explicitly planned to continue to be loose, the lack of consumer price inflation must be seen as a lack of organic demand.

Chinese consumers are simply not interested in consuming.

Regardless of what GDP forecasts say, China’s current economic condition is demonstrably one of stagnation, stagflation, and quite probably outright deflation.

Expanded GDP growth in such circumstances can only be illusory growth which does nothing to increase the prosperity of either the people or the nation as a whole.

Housing Is Still An Albatross

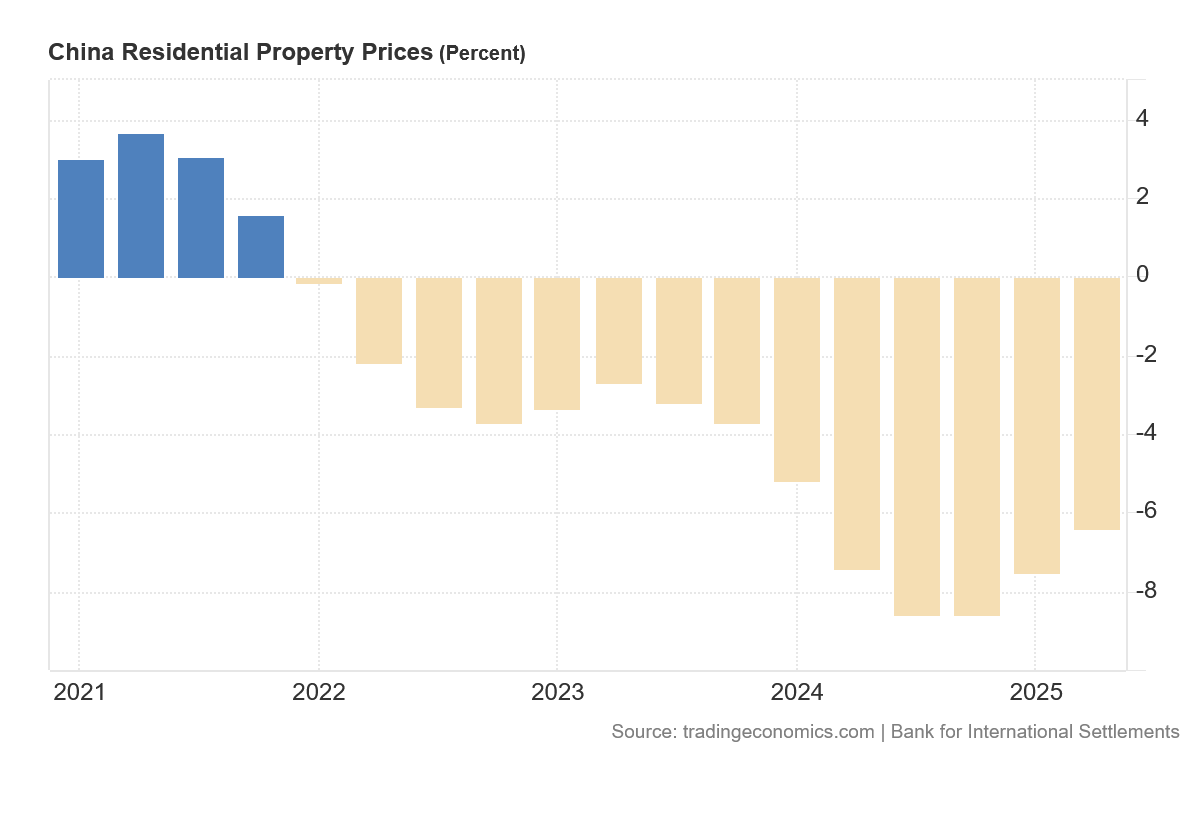

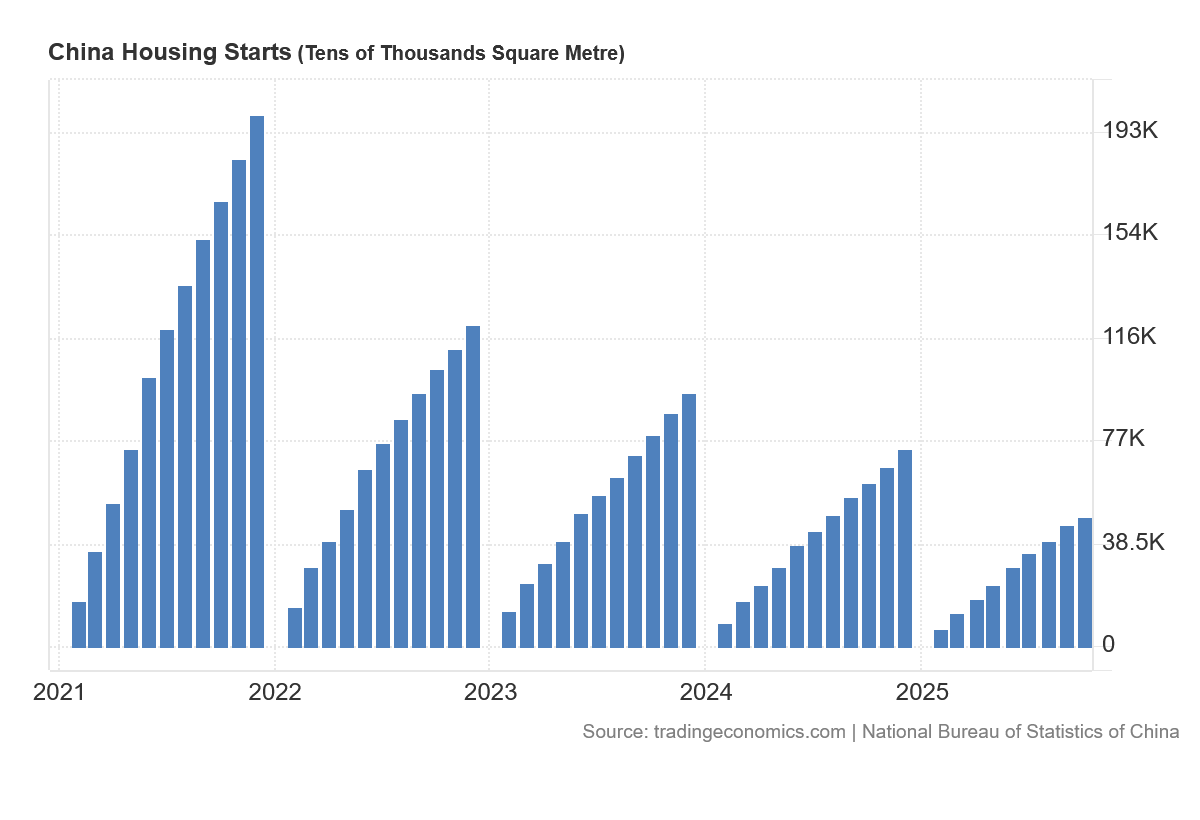

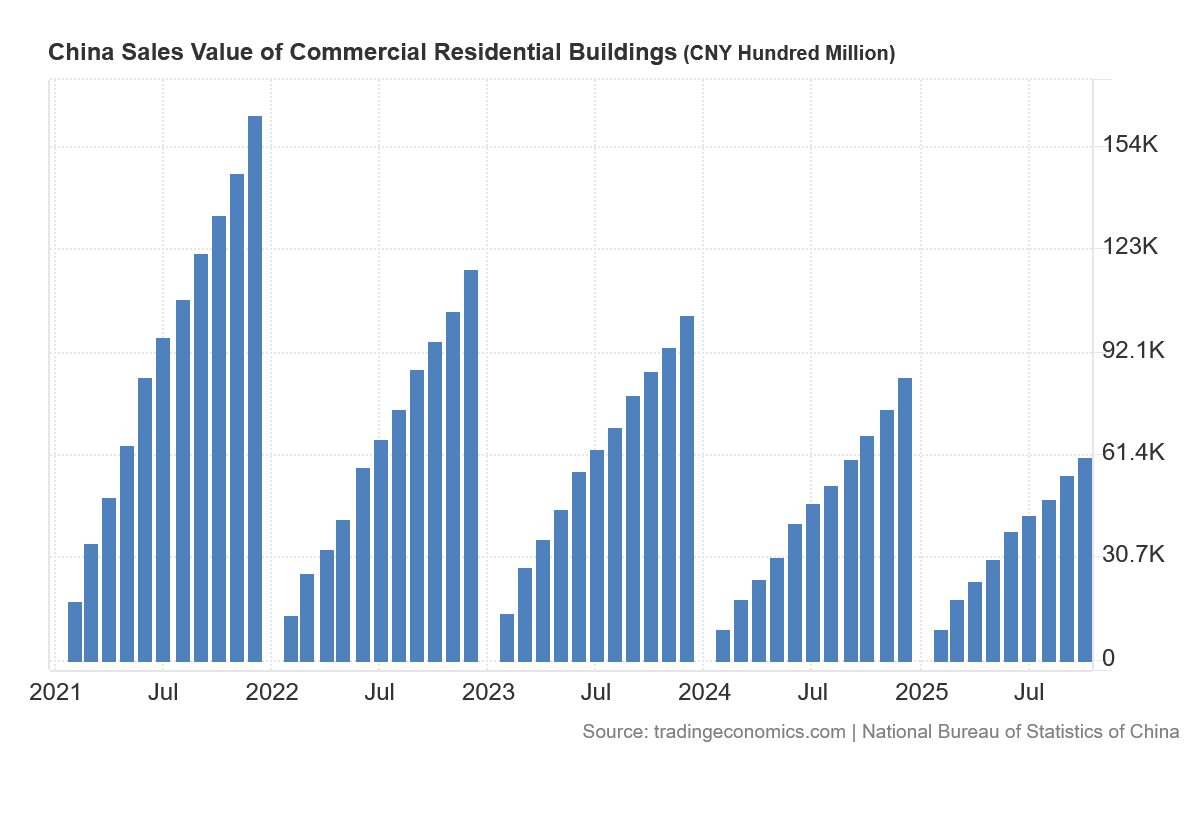

No commentary on China’s economic circumstances would be complete without touching on the state of affairs in China’s housing industry. The collapse of China’s housing industry has been the lead story regarding China’s economic situation, going back to the collapse of Evergrande in 2021.

The story has not improved since then. It has, instead, continued to deteriorate.

China’s housing prices are still in freefall.

Unsurprisingly, housing starts are also on the decline.

New home sales are likewise heading south.

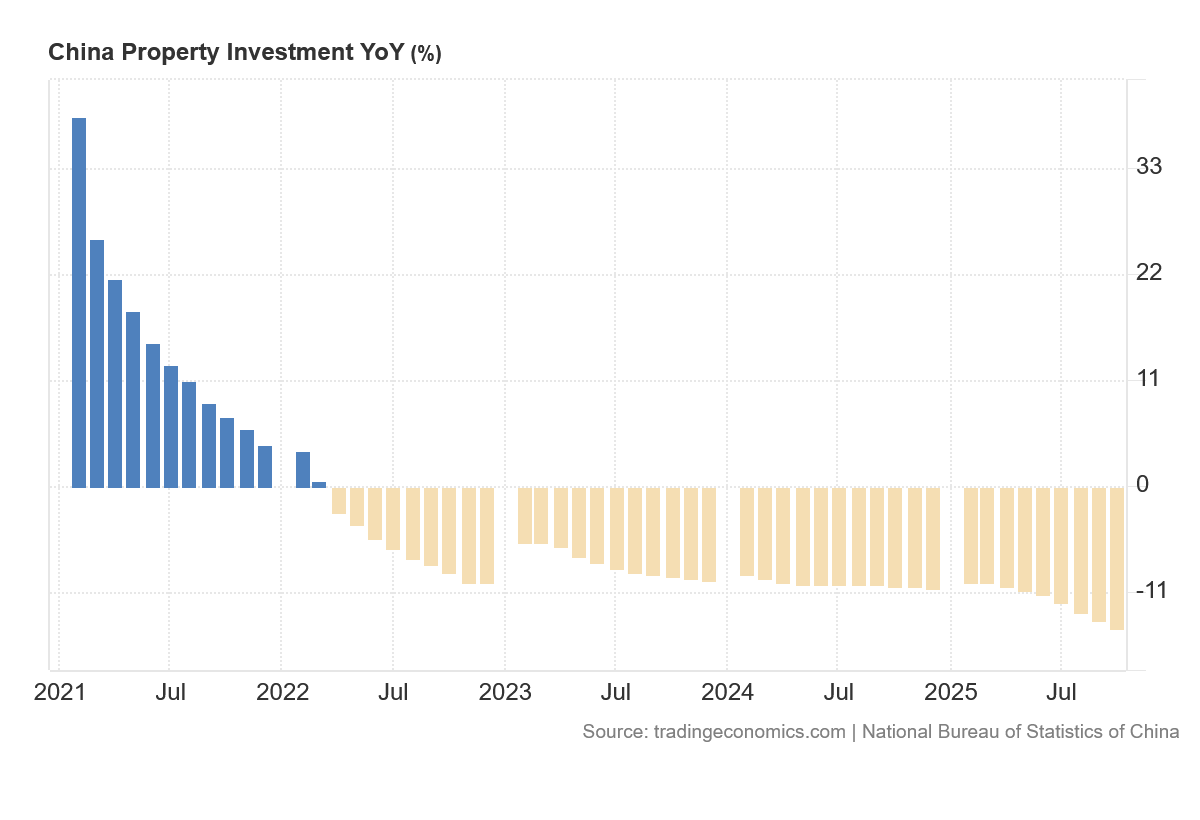

Unsurprisingly, property investment in China has also collapsed.

There is no disputing the reality that China’s real estate bubble was well and truly burst in 2021, and has been deflating ever since. The size of that bubble and the magnitude of the damage it is causing to the Chinese economy is illustrated by the reality that, four years on, the bubble is still deflating.

The continued decline of housing in China is not merely a decline in pricing. It is wealth destruction on a massive, even apocalyptic scale. What wealth China’s nascent middle class has accumulated is largely tied up in real estate, and the collapse of real estate values and real estate investment means that wealth is evaporating.

One reason Chinese consumers are indifferent to consuming is they are losing the means to fund consumption, as the collapsing housing bubble sucks up all their available wealth.

Ominously, one sign the wreckage is far from complete for China’s housing markets is that China Vanke, which last year was flashing warning signs of being China’s “Evergrande 2.0”, is facing an imminent bond default.

Late last week, China Vanke sought to extend repayment of a maturing bond issue, a move which tested the mettle of investors who had already been hit with the shock of an earlier bond extension request.

Shenzhen-based Vanke, once the nation’s largest builder by sales, told bondholders Monday that it was seeking a one-year delay to pay the 2 billion yuan ($283 million) note originally due Dec. 15, people familiar with the matter said. The 3% interest would also only be paid after a year. The proposed changes would require at least 90% approval from holders, based on the note’s prospectus.

Vanke followed that up just days later with a request to extend a second bond issue due on the 28th.

Bondholders have nixed an extension on the first bond issue, putting Vanke on a countdown to outright bond default.

Bondholders rejected the proposal to delay maturity, leaving Vanke with a five-business-day grace period to pay 2 billion yuan ($280 million) under the deal terms.

The setback for Vanke, one of China’s highest-profile developers with projects in major cities, has renewed concerns that the country’s property sector could slip back into crisis.

The industry, once contributing up to a quarter of GDP, was hit by a liquidity crunch in 2021 after tighter regulations, leading to dozens of defaults.

Vanke, as I noted last year, could be particularly troublesome for Beijing, as it is one of the “state owned” developers in China’s property sector. The previous high-profile collapses, Evergrande and Country Garden, were privately owned.

What are the ramifications of a state owned enterprise failing? Those are hard to calculate, because such a failure strikes at the credibility of the state itself.

Will Beijing step in at the last minute to bail the developer out, or at least resolve the bond default? There is no reporting as of yet to indicate that Beijing is inclined to do so, but it may not have much choice. Given the contagion effect that Evergrande’s collapse had on private property developers, Vanke going under could precipitate a similar scenario among the state owned developers.

In a top-down economy such as China’s the state owned enterprises are not merely “too big to fail”, they are the ones for which failure is not supposed to be an option, ever—until it is.

Given the ongoing toxicities within China’s housing markets, the turnaround prospects for China Vanke are best assessed as between slim and none. Beijing either bails the company out or watches a fresh wave of corporate collapses roll through the real estate sector.

After four years of bubble deflation, China may have yet to experience the worst of it.

What Is Goldman Smoking?

When one looks across the totality of the current data on China’s economy—data that comes from China itself, officially reported by Beijing—a simple question naturally arises regarding Goldman Sachs’ economic projections for China:

What are they smoking?

Indeed, one has to question the basis for charting any economic growth for China, either this year or next, or any time soon at all. Other than paper numbers propped up by government spending, growth is not the current narrative of China’s economy.

Stagnation, stagflation, and outright deflation are the current narratives.

Is China’s economy about to implode spectacularly? That is a possibility, although perhaps not a probability. What is certain is that China’s economy is still very much in the deflationary trap I described last year. Even without a complete implosion, if current trends continue there will be no significant economic growth in China, not in real terms.

If Vanke and other state owned developers collapse, could that in turn trigger a banking, liquidity, and ultimately political crisis? That is very much a possibility, as the Evergrande collapse already produced one mini-crisis, with mortgage holders protesting the situation by withholding mortgage payments.

That a fresh cycle of corporate defaults carries outsized political risks for Beijing has already been demonstrated. Whether that risk becomes an existential crisis for the CCP is at present unknowable, but the possibility has already been shown to exist.

With other countries looking askance at China expanding its exports to the world, China’s “go to” economic policies are increasingly being blocked by outside geopolitical forces. Unless other countries elect to allow China to increase exporting into their markets, increasing export volumes is not a viable path for China’s future economic growth.

Yet without exports, where China gets the economic growth to raise its per capita GDP is very much an unknown. If China does not raise its per capita GDP significantly, any increases in consumption which might be generated by various government stimulus measures will be at best transitory and will drive consumption most likely along unsustainable channels.

How the net effect of these reported, documented, official economic realities for China translates into optimistic growth assessments for China’s real gross domestic product is also very much an unknown. For China to experience good economic growth, a number of negative trends need to reverse, and at present there are no signs that any of them are about to do so.

Unlike the Vampire Squid, I am disinclined to make a discrete projection about China’s future economic growth, mainly because China’s future economic outlook is bleak heading towards catastrophic.

Goldman Sachs earned the moniker “Vampire Squid” after journalist (and now fellow Substacker) Matt Taibbi’s depiction of the investment bank in the lede paragraph of his 2010 Rolling Stone piece on the Great Financial Crisis.

Corporate Finance Institute. Consumption. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/consumption/.

Very impressive work, Peter. You’ve got great data to support every brilliant point you’ve made. Frankly, I’m surprised at Goldman Sachs’ prediction - have they not been paying attention to China’s underlying financial problems? Their prediction is so clueless that I find myself cynically suspecting some underhanded financial ploy on their part, to game the system in Goldman Sachs’ favor.

And as you point out, China usually gives a more positive picture of their economic than is warranted. China’s leaders have been consistently lying about everything for decades. As an example from my memories, after Nixon went to China - opening up the Iron Curtain there for the first time in decades - China started releasing propaganda about what a paradise Mao’s communist system was. They said that prostitution had been completely eradicated - there was not a single prostitute in all of China. Even as a naive 15-year-old, I thought, wait, I’m supposed to believe that out of 800 million people there is NO prostitution going on? Um, I don’t think so. Eventually, the West found out about the 100,000 or so Chinese peasants who starved to death in that “paradise”. It’s been just one big lie after another, and no one in power within China dares to speak the truth about anything.

Thank you for your excellent work, Peter. I always feel that I’m getting an accurate assessment from you!

I don’t pretend to understand probably most of what you said, even though it was plain English. I’ll have to read it probably two or three more times to see how much of it will stick. I have thought for a long time that China is on a downward trend because of your previous reporting and others. I think what scares me about it is it makes China dangerous from a military standpoint. They will have to do something to make the world think they are strong. I haven’t seen too many detailed analysis’ of the strength of China’s military, but if they try to disturb Taiwan, that will be a big deal. Once again you’ve gotten my attention and I’m going to become a paid member. I thank you, I bless you for your hard work and I wish you good health and the greatest success.