Is Wall Street Giving Up On A China "Recovery"?

Will China's Present Be The United States' Future?

It comes as no surprise that China Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s media mouthpiece to the world, reliably sings the praises of China’s “strong” economy on the rebound after emerging from Zero COVID.

Miao Yanliang, one of the CF40 members and chief strategist and executive head of the research department at the China International Capital Corp, said that China has a recovery "probably stronger than expected", with a 5 or 6 percent growth goal in 2023.

Even when analyzing the inarguably grim global economic situation, China Daily finds ways to praise China’s economic situation.

China's inflation level is much lower than that of major developed economies, which can be mainly attributed to the following three aspects. First of all, the divergence between China's economic cycle and that of Europe and the US, and the slowdown in China's internal demand, which curbs overall price increases. Second, the current round of high global inflation is mainly driven by the sharp rise in commodity prices, which are impacting the Chinese economy in the form of imported inflation, as evidenced by a significant rise in the producer price index. Finally, China's CPI composition and major developed economies' CPI composition differ significantly. In China's CPI basket, the weighting of sectors such as housing and food are big, but price increases have not been burdensome.

At the same time, due to China's expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, China's economy is experiencing a slow stabilization. From January to October, the added value of China's enterprises above a designated size of 20 million yuan ($2.84 million) in revenue increased 4 percent year-on-year, 0.1 percentage point faster than that from January to September. In October, the added value of such enterprises increased by 5 percent year-on-year, 0.2 percentage point faster than that in the third quarter, and 0.33 percentage point higher month-on-month. Most importantly, with China updating its COVID-19 prevention and control measures, a stronger impetus will be injected into the Chinese economy as China's capital market will mount a strong response.

We should expect nothing less than propaganda from a political party newspaper.

However, we still should take note when Wall Street starts to ignore the propaganda and shows doubt that all is as it should be in The Middle Kingdom. There are good reasons to believe China’s present economic concerns may be the US’ future economic crisis.

Certainly last month Wall Street and the financial media were quite happy to share China Daily’s optimism.

Britain’s The Guardian offers up a stellar example of corporate media cheerleading for China, projecting that China’s economy is “predicted” to power global oil demand through the remainder of 2023.

Global demand for oil this year is on track to rise to a record 101.9m barrels per day as China leads an economic surge among developing nations, the world’s leading energy body has forecast.

The International Energy Agency’s predicted daily average for 2023 is 2m bpd higher than last year’s figure.

Just over a month later, however, and the media is taking a more pessimistic view of things.

Until a few weeks ago, Chinese shares were among the best-performing in the world over the previous six months as investors bet on the country’s economic recovery after the lifting of pandemic restrictions.

But since April 18, when China released figures on its first-quarter economic output, stocks of Chinese companies around the world have lost about $540 billion in value, according to CNN calculations. Investors trimmed their exposure to China amid economic uncertainty in the country, rising geopolitical tensions and Beijing’s crackdown on international consulting firms.

Wall Street is even showing signs of (finally!) doubting China’s “official” economic data.

Official figures on Tuesday are expected to show rapid year-on-year growth in industrial output and retail sales for April, with both of those key datasets likely accelerating from March. Fixed-asset investment through the first four months of 2023 is also projected to have gathered pace.

The figures come with a major caveat: they all compare to an extraordinary time period in China last year, when the manufacturing and finance hub Shanghai was locked because of spreading Covid cases, and restrictions on movement slowed or halted activity elsewhere.

Part of the pessimism is undoubtedly due to China’s failure to meet economists projections about how China would do in the latest statistical release.

China’s industrial output and consumer spending have fallen short of expectations, fuelling doubts over the strength of the country’s rebound after it dismantled its zero-Covid policy.

Youth unemployment hit a record while a key measure of investment also lagged estimates, casting a shadow over the outlook for the world’s second-largest economy.

Industrial production added 5.6 per cent last month from a year earlier, well below forecasts of a 10.6 per cent rise. Retail sales expanded 18.4 per cent year on year, also missing forecasts. The high rates of growth partly reflect a contrast with lockdowns last year in Shanghai, the country’s biggest city.

The economy which was supposed to come roaring back from Zero COVID simply….hasn’t.

So far has China fallen short of economic expectations that on Sunday Rockefeller International chair Ruchir Sharma took to the pages of the Financial Times to take his fellow Wall Street denizens to task for their feckless analyses regarding China.

Something is rotten in the Chinese economy, but don’t expect Wall Street analysts to tell you about it.

There has never been a bigger disconnect, in my experience, between some of the rosier investment bank views on China and the dim reality on the ground. Perhaps reluctant to back off their calls for a reopening boom this year, sellside economists keep sticking to their forecasts for growth in gross domestic product in 2023, and now expect it to come in well above 5 per cent. That’s even more optimistic than the official target, and wildly out of line with dismal news from Chinese companies.

Sharma proceeds to list several of the ways in which Wall Street has simply missed the mark on China.

Corporate revenues lag GDP growth. While a projection of 5% growth in GDP implies corporate revenue growth of 8% based on historical norms, reported corporate revenue growth during the first quarter was 1.5%.

Weak revenue growth is across the board for China, coming in below GDP growth in 20 of 28 economic sectors.

Imports fell by 8% in April, when the anticipated boom in consumer demand should have driven import increases.

Credit growth has collapsed, coming in at only ¥720 Billion ($103 Billion), half what was forecast.

Youth unemployment is rising, and is already above 20%.

Sharma’s thesis is that China’s economic growth model, which has for much of the past 15 years been highly dependent on government stimulus spending, is now too saddled with the resultant debt to do much lifting of the Chinese economy.

A growth model dependent on stimulus and debt was always going to be unsustainable, and now it has run out of steam. Much of the stimulus over the past decade had flowed through local governments in China, which used their own “financing vehicles” to borrow and buy real estate, propping up the property markets. Those vehicles are fast running out of cash to finance their debts, which is curbing their investment in the property market and industry as well. Industrial sectors are slowing faster than the consumer-related businesses at the centre of the reopening story.

Sharma concludes with the complaint that rosy analyst forecasts on China has cost investors "hundreds of billions.”

While analysts may have little to lose from rosy forecasts, the rest of us do. “Boomy” chatter has contributed to investors’ loss of hundreds of billions of dollars in China in just the past four months. Further, global growth may prove weaker than expected in 2023, since the hope is that a US downturn will be countered by the China reopening boom, which may never come. It is time to expose this charade before the fallout gets worse.

While Sharma’s complaints about Wall Street overlooking China’s manifest economic deficiencies have some merit, what he fails to appreciate is that the data has always been there.

Wall Street may have deluded itself with the “reopening” narrative, but even in January there was data to suggest that a certain pessimism was warranted.

Long before SARS-CoV-2 made its entry onto the world stage, China’s economy was showing signs of gradual stagnation and decline—in 2019 there was no denying that China’s best economic years were already behind it.

It is against this backdrop of gradual long-term decline that China’s current economic conditions must be assessed. Beijing has to not only resolve how to address the immediate dislocations brought on by Zero COVID and the pandemic, but also how to contend with an economic model that has been working less and less well for years.

It was plain by February that China’s “reopening” was not producing the rises in commodity and oil prices that were necessary if Chinese production and demand were to be rising to any significant degree.

While the price of crude oil has been rising over the past few days, for most of January Brent crude was drifting somewhat lower.

If China’s economy were expanding at the pace forecast by most economists and China watchers, the price of oil would have been in a steady increase since December. While recent price rises arguably are indicative of a resurgent Chinese economy, those increases have only happened recently, indicating at a minimum that China’s return to economic expansion is still extremely recent.

Nor is it just the historical market data that works against the “reopening” narrative.

Zero COVID has allowed factories to reopen free from COVID containment protocols, but that has in turn allowed workers to express more dissatisfaction with their work situation and pay.

This year in China there have already been at least 130 factory strikes, more than triple the number in the whole of 2022, according to data compiled by the China Labour Bulletin (CLB), a Hong Kong-based non-governmental organisation.

Even in China, when workers aren’t paid, they tend to get rather testy about doing any more work!

Additionally, the return of summer heat is once again adding stress to China’s power grids.

The power load of the China Southern Power Grid Monday reached a historical high of 200 gigawatts, one month earlier than last year, domestic media Jiemian reported.

The state-owned grid network, which covers the five southern provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Hainan, expects a major year-on-year jump in the power load this month, the report added.

To cope with peak demand during the summer heat wave, the power supplier said it has stepped up cooperation to ensure cross-provincial electricity supply and completed transmission network maintenance.

The rise in electricity demand carries an added cost burden for China not seen in Europe or the US, because China uses proportionally more expensive coal rather than natural gas to run its power plants.

The problem for China is that it’s treating coal-fired power the way the US and Europe treat gas. Electricity demand tends to rise and fall throughout the day. To accommodate this variability, grids were traditionally structured around always-on, so-called “baseload” power plants, plus a fleet of “peaker” plants that could be switched on and off to follow the morning and evening surges in demand.

As anyone who’s tried cooking with both a gas and charcoal-fired grill will know, solid fuel is ill-suited to this sort of operation. Coal plants, like charcoal barbecues, take a long time to be coaxed to and from their operating temperatures. On top of that, the brute machinery needed to shuttle sooty rocks around means that they’re simply more expensive to build — around $505 per kilowatt of capacity in China at present, according to BloombergNEF estimates, compared to $290/kW for gas.

Additionally, China is likely to encounter additional economic headwinds from an anticipated “second wave” of COVID infections.

XBB has been fueling a resurgence in cases across China since late April and is expected to result in 40 million infections a week by the end of May, before peaking at 65 million a month later, local media outlet the Paper reported Monday, citing a presentation by respiratory disease specialist Zhong Nanshan at a biotech conference in the southern city of Guangzhou.

His estimate provides rare insight into how the much anticipated second wave may play out, with immunity among the country’s 1.4 billion residents waning nearly six months after Beijing’s sudden dismantling of Covid Zero curbs saw coronavirus run rampant. In the wake of the pivot to living with the virus, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention stopped updating its weekly statistics earlier this month, leaving a question mark over Covid’s impacts.

While media hyperventilating over COVID has been shamelessly overblown even when discussing China, a significant rise in the number of sick people—and therefore sick workers—is not going to help boost the economy’s output. One hardly needs to be conversant with finance or economics to understand that people saddled with flu-like symptoms are less productive even when they are able to work.

Not only has the data never really supported the narrative of a robust reopening of the Chinese economy post-Zero COVID, but the data suggests that there is not going to be any robust reopening any time soon. Wall Street’s China narratives have always been more wishful thinking than insightful analysis.

Where China becomes a cautionary tale for the US is its debts. Chinese debt loads are increasingly proving a barrier to future economic growth.

China’s debt problem is compounded by the arcane methods China uses to fund its government stimulus programs. Stimulus programs are generally carried out at the local government level, but rather than receiving direct support from Beijing for these programs, local governments are tasked with funding the spending efforts on their own. The end result has somewhat predictably been a steady rise in local government debt over the years—and in creative “off the books” ways of managing that debt.

LGFVs play a key role in funding Chinese infrastructure projects, one of the biggest growth drivers for the world’s second-largest economy. But some analysts say they have become the “black holes” of the country’s financial system, with surging debtloads exceeding US$9 trillion and weak revenues beginning to alarm investors.

Yet merely keeping the debt off local government balance sheets does not make the debt magically cease to exist. Even if local governments in China should do the unthinkable and repudiate the debts of local government financing vehicles, the surge in debt defaults would reverberate throughout the Chinese economy.

Beijing’s reflex response to the mounting (hidden) debts at the local government level has been principally to tell local governments to get rid of the debt.

In a key December meeting outlining this year's financial policy agenda, President Xi Jinping pressed provincial governments to guard against risks of hidden debt and take resolute measures to "curb any increases in debt and mitigate existing debt."

In recent speeches, finance minister Liu Kun has again called for further efforts to control hidden debt risks and transform local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) into market entities, rather than simply operating as borrowing platforms.

"From the debt restructuring tasks assigned at the provincial level, it is evident that more efforts will be needed this year than in previous years," a person from an LGFV said. Several other LGFV sources told Caixin that any increase in new hidden debts will be "absolutely prohibited while disposal of existing debts must be accelerated."

Diktats from the CCP notwithstanding, local governments in China do not have an abundance of options for funding Beijing’s edicts.

Facing financial strain, local authorities are finding their options for disposing of risky debts increasingly limited. Most of them have relied on debt restructuring to extend maturity and reduce the interest burden to seek short-term relief, while others are attempting to cut funding costs by various means.

In its quarterly report, the National Institution for Finance & Development (NIFD) said the extent to which local governments have disposed of their debt varies significantly based on their financial status and the strength of the local economy.

Regions with weaker overall economic and financial capacity are likely to seek short-term remedies with long-term costs, said the NIFD.

Already some LGFVs and the local government budgets they facilitate are hovering dangerously close to outright debt default.

No LGFV has failed to repay a bond so far, although there have been defaults on non-standard debt, which usually refers to debt that isn't traded on the interbank market or stock exchanges such as trust loans, bank acceptance bills and accounts receivable.

Small cities where government borrowing has exceeded their ability to repay them are particularly at risk. For instance, in Weifang, Shandong province, 12 defaults related to LGFVs' non-standard debts have been flagged so far this year, according to Guosheng Securities.

Cities like Kunming are rumored to be about to default on major debts, although the city itself is still trying to dispel such rumors.

The latest rumours, which circulated on social media in China on Tuesday, said some LGFVs in Kunming, the capital city of inland Yunnan province, were having “great difficulties” in paying back debts and have used social security funds and housing provident funds for repayment – a major violation of the rules.

The State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Committee of Kunming said in a statement that the information was fake, and it had “taken legal means to protect our legitimate rights and interests”.

So far, there have been no reports of an LGFV default in public markets, and some investors say they have faith that governments will guarantee the repayment of such debts.

In Guiyang, officials seem to be largely just trying to bury the problem and hope it will somehow go away.

Guiyang, the capital city of Guizhou, had tried “every technical means” to resolve its debts, and “if debt repayment funds are not in place in time, debt risks may occur at any time”, the city’s finance bureau said in a 2022 work report published last week. The report was later removed from its website.

While actual debt defaults may be avoided, bailouts from Beijing are quickly becoming the most likely scenario—which would probably doom any significant government stimulus spending in the near term.

China, however, is far from the only country burdened with significant debt loads.

In the United States, public debt has surged during and after the government-ordered recession in 2020.

At the same time, household debt has also risen post-COVID lockdown.

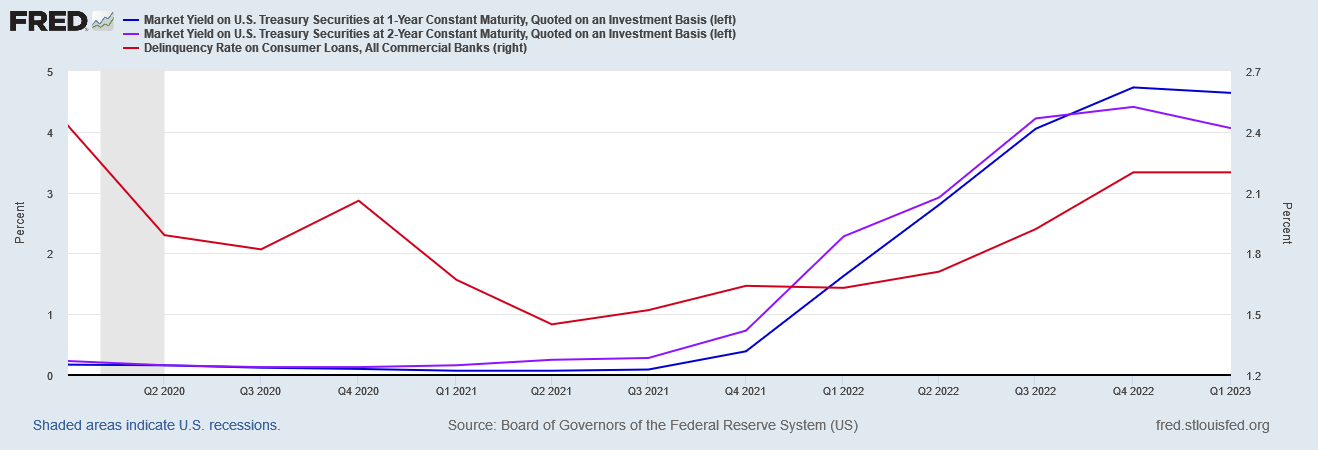

As the debt load has risen for US households, so have delinquency rates.

While in China the debt problem centers on hidden off-balance-sheet financing, in the US the catalyst for crisis has been rising interest rates, which makes debt service progressively more expensive.

It is hardly coincidental that household default rates have risen as interest rates have risen.

No matter the country, no matter the economic system, rising debt burdens invariably present a threat to current economic growth and future economic prosperity. Even though a measure of debt is necessary to spur investment in any economy, successful investments service and soon retire that initial debt.

Rising debt levels suggest that the investments made are not successful enough to service the debt.

No one can prosper when one is in hock up to their eyeballs. It necessarily follows that no country can prosper either under such circumstance.

China cannot prosper under such circumstance.

The United States cannot prosper under such circumstance.

Yet rising and even extreme levels of debt are the economic reality in both China and the US. These debts must be paid, yet money spent to service debt is not money that can be spent to drive consumption or invest in building out supply chains. Money spent to service debt is not money that can be used to build up wealth.

Wall Street is losing faith in the China narrative, in large part because China’s debt chickens are coming home to roost.

How will Wall Street react when those same chickens come home to roost in the US?