On monkeypox, one point deserves constant repetition: no one has yet died during the current global outbreak1. Even though the virus continues to spread outside its traditional environs of West and Central Africa, favoring for reasons as yet not fully understood gay and bisexual men2, it has yet to claim any lives.

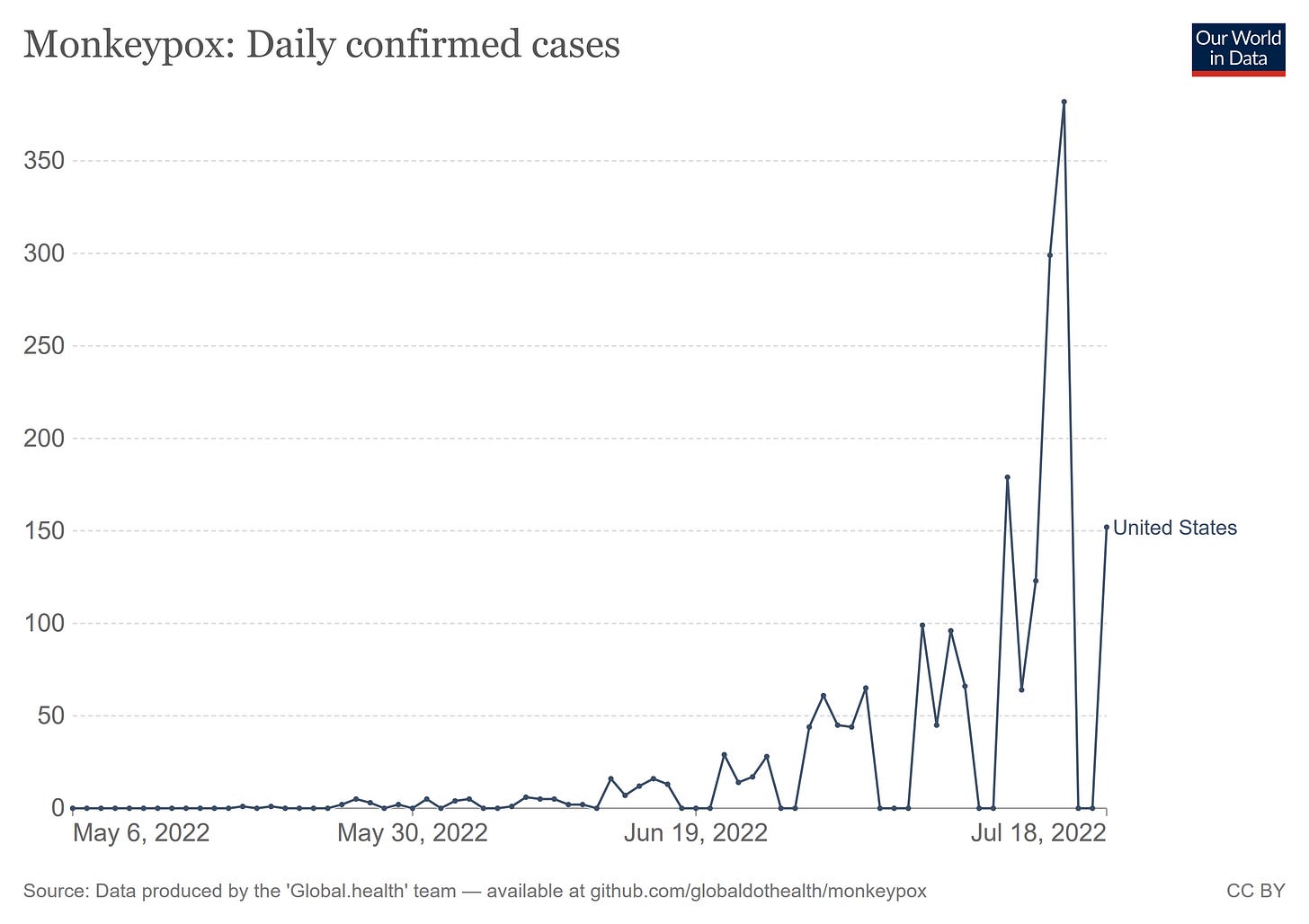

This has not stopped the media from wringing its collective hands, however, as cases in the US have jumped dramatically in the past week, catapulting the US into the number 4 position for the most cases reported.

This continued rise in case totals is what led former FDA Commissioner (and current Pfizer board member) Scott Gottlieb to state on CBS that the virus had not been “contained”.

"I think at this point, we've failed to contain this," Gottlieb said on CBS' "Face the Nation." "We're now at the cusp of this becoming an endemic virus where this now becomes something that's persistent that we need to continue to deal with."

Simply A Matter Of Increased Testing?

As Fox News has noted, the increase in US cases coincides with an increase in testing for monkeypox.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are now 1,814 confirmed cases across the country.

Where monkeypox testing has increased, so have case counts.

While increased testing can account for some of the increased case reports, however, the spike in cases is not wholly attributable to the additional tests performed.

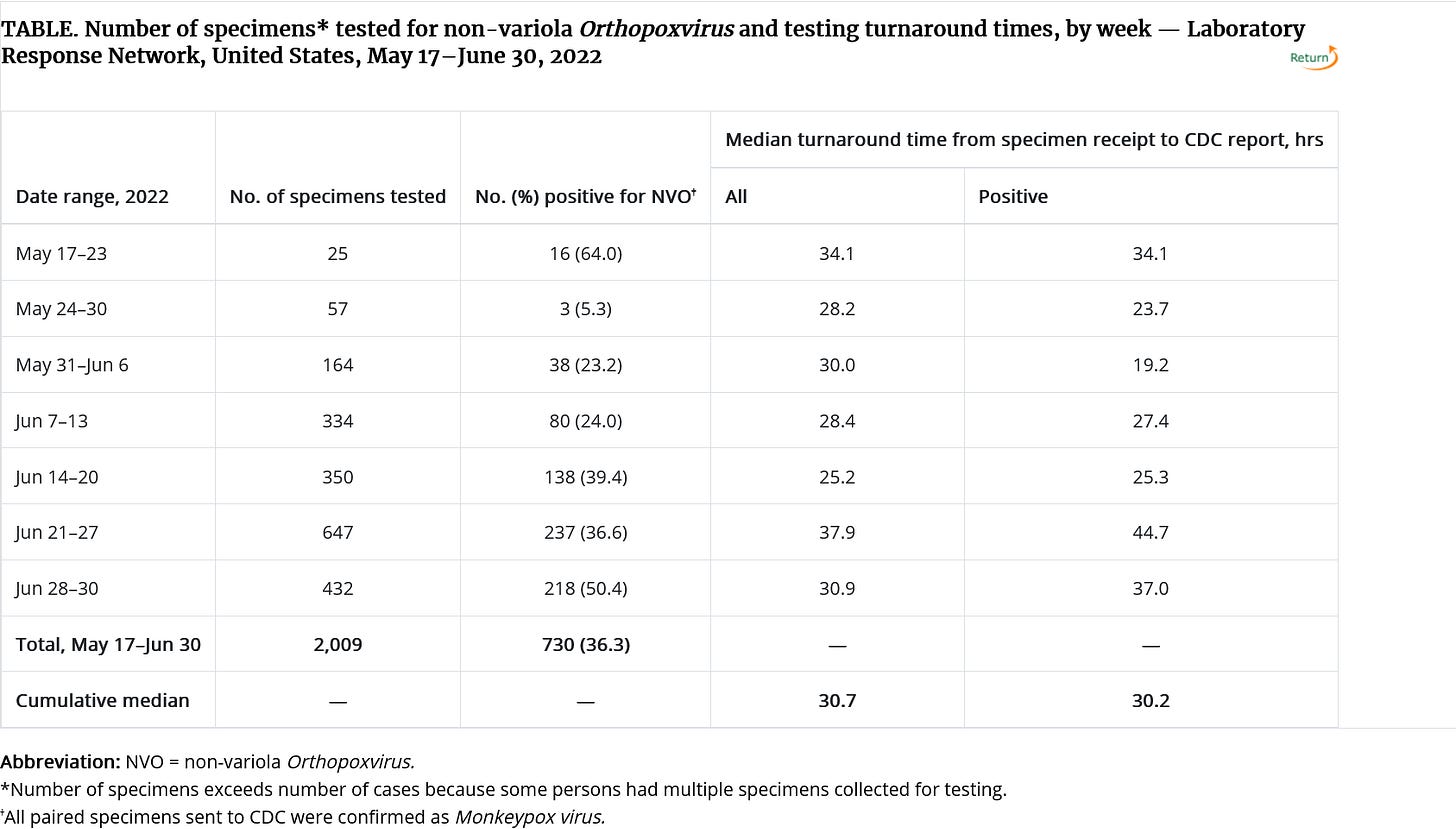

Non-Variola Orthopoxvirus (NVO) testing is largely being performed through the Laboratory Response Network3, which between 17 May and 30 June conducted 2009 tests, 730 of which returned positive for NVO (test positivity rate 36.3% overall). However, when the tests are broken down week by week, there is a trend of increasing test positivity over time.

Rising test positivity means the rate of spread is increasing. While there is inadequate data with which to compute an effective reproduction rate at this time, the rising positivity rates indicate that reproduction rate is well above one.

Bear in mind that researchers at the Institut Pasteur have calculated the base reproduction rate for monkeypox as being anywhere from 1.46 to 2.67. The increasing test positivity rate dovetails with a reproduction rate that is closer to the high end of that range.

Yet despite the apparent increasing rate of transmission, the US has only ~1800 cases. In a country of over 330 million people, that’s just not a lot of cases.

Spreading Globally, Not Just In The US

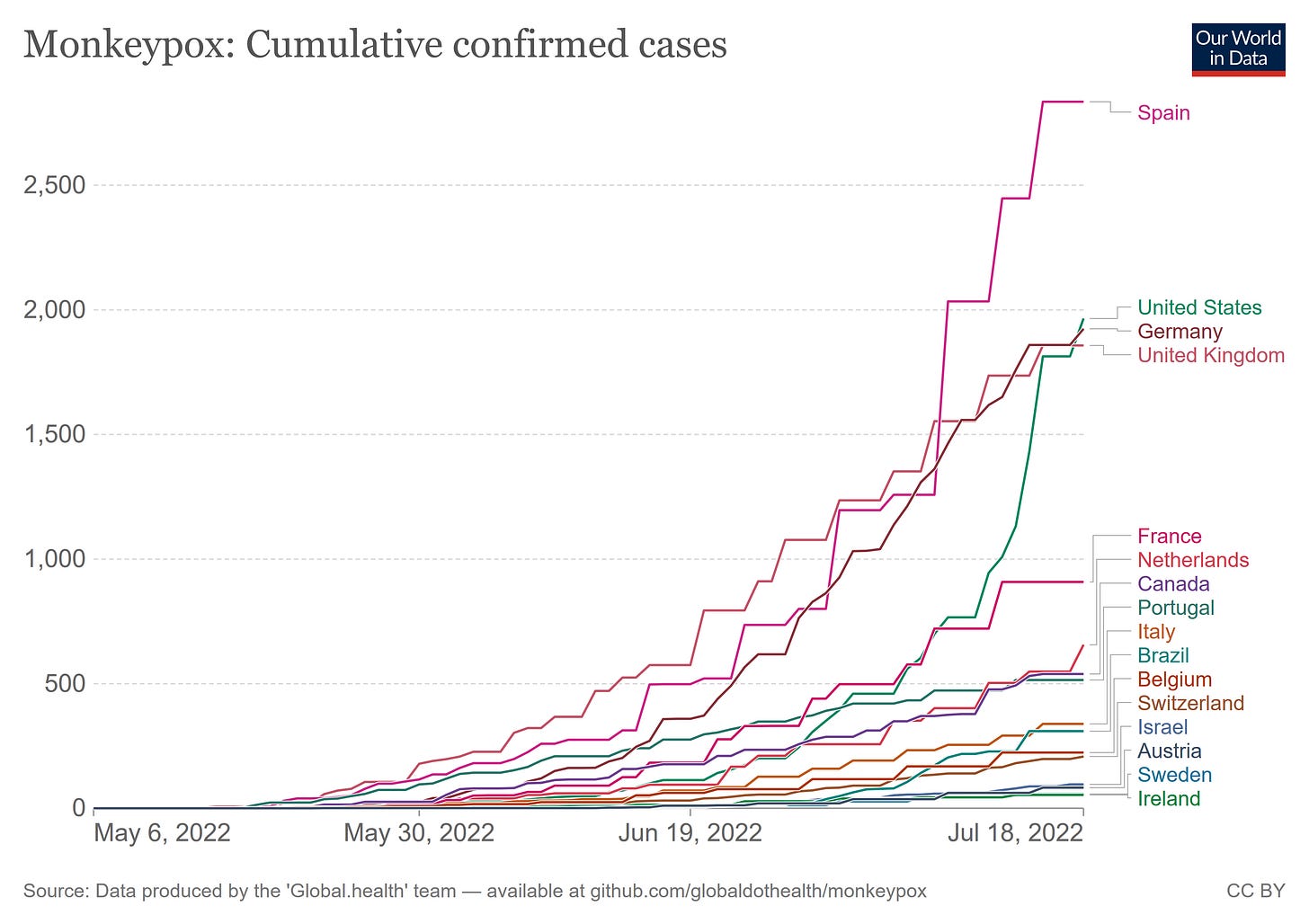

A quick survey of the cumulative case counts by country (courtesy of Our World In Data) shows that monkeypox continues to spread globally as well.

Notably, the rate of spread in Spain has increased more than in either Germany, the United Kingdom, or the United States, which countries in turn have shown a greater increase than France. Why different countries are experiencing dramatically different rates of transmission is unknown at this time.

All of the countries where monkeypox has spread the most are more or less equal in terms of economic conditions and access to healthcare, There is not a case to be made for any form of social iniquity as a driver of monkeypox infection rates in the countries where the disease is currently most prevalent, which makes the divergent rates of spread particularly intriguing.

However, the virus is also spreading to more and more countries. This past week India became the first country in the WHO South-East Asia region to report a case.

The first case of monkeypox in WHO South-East Asia Region has been reported from India, in a 35-year old man who arrived from the Middle East earlier this week.

“The Region has been on alert for monkeypox. Countries have been taking measures to rapidly detect and take appropriate measures to prevent spread of monkeypox,” said Dr Poonam Khetrapal Singh, Regional Director, WHO South-East Asia.

It is a testament to how the global presentation of monkeypox has shifted from a primarily zoonotic disease that news accounts by and large no longer highlight a lack of known travel or other connection to West or Central Africa. Human-to-human transmission has become an accepted norm for the virus.

The increasing global spread of the virus is leading the World Health Organization to convene a second meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee to discuss whether or not to declare monkeypox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

This WHO meeting will be the second for the emergency committee, with experts set to decide on if monkeypox cases constitutes a public health emergency which should be of 'international concern'.

A PHEIC (Public Health Emergency of International Concern) is the highest formal declaration alarm the WHO can raise for the spread of a disease like monkeypox.

The last committee meeting found that the situation had not yet met the threshold - but with case numbers rising, the health agency warns of their concerns.

While the continued spread of the disease is cause for concern, several aspects of the outbreak are the same as they were at the last committee meeting, which declined to declare monkeypox a PHEIC:

The WHO risk assessment for monkeypox is still “moderate”—although for the European Region it is assess as “high”—based on the most recent Disease Outbreak News bulletin, dated 27 June 2022. That no further update has been issued during the intervening weeks, even as the cases have increased more than five fold, suggests that the WHO risk assessment is still “moderate”.

The vast majority of cases are among gay and bisexual men, something that is confirmed by the corporate media reporting on the outbreak.

To repeat the point stated at the beginning, there have been no deaths outside of Africa.

Do these realities add up to a public health “emergency”? We shall know after this Thursday.

Is Monkeypox Endemic Outside Of Africa?

However, Scott Gottlieb and the rest of the corporate media talking heads remain very much behind the curve on the salient point of endemicity. The apparent self-sustaining nature of the global outbreak means the virus is almost certainly endemic well beyond its historical confines of West and Central Africa.

The real question on endemicity is whether or not there is an animal host able to harbor the virus outside of Africa, thereby ensuring future global outbreaks. As I have noted previously, in regards to an article in The Atlantic on monkeypox endemicity, there is a very good chance this has already happened.

This concern likely comes too late, however. If we accept the premise of “hidden” transmission within Europe and North America—a necessary component of understanding how European cases of monkeypox can have an extraordinary number of nucleotide substitutions—we also have to accept the likelihood that monkeypox has already found an animal host outside of Africa in which to linger when not spreading person-to-person.

Given the enduring nature of the global outbreak, which has refused to follow the historical pattern of petering out after a few weeks, an expanded endemic region for monkeypox has to be acknowledged, with significant probabilities that the virus is now endemic in both North America and Europe. If that should prove to be the case, then this global outbreak is only the first; it will not be the last.

I Repeat: No One Has Died From Monkeypox

Yet we must not forget, throughout all the media pearl-clutching over monkeypox, the number of deaths attributed to the virus: zero.

No one has died from monkeypox outside of Africa. At all.

This is significant because even the milder West African clade of the virus can have a case fatality rate of around 3%.

The case fatality ratio of monkeypox has historically ranged from 0 to 11 % in the general population and has been higher among young children. In recent times, the case fatality ratio has been around 3–6%.

During the now largely forgotten West African outbreak earlier this year, some 72 people died, although monkeypox was not confirmed in most of them.

With more than 12,000 cases worldwide and zero deaths, the global variant of the disease is behaving quite atypically from its West African ancestors.

Ironically, such variances have been noted by a number of virologists, who would rather virtue signal than engage in meaningful research or discussion—as evidenced by their screed from last month calling for a “non-discriminatory and non-stigmatizing nomenclature for monkeypox virus”. I noted last month their seeming half-awareness of important variances between monkeypox as it presents in Africa and monkeypox as it has presented everywhere else.

That the virus is no longer endemic to just Africa is significant because of another data point presented by the authors: the strain of monkeypox involved in the current “non endemic” outbreak is not “zoonotic”, but spreads person to person.

We also suggest naming a new clade, containing genomes sampled between 2017–2019 from the UK, Israel, Nigeria, USA, and Singapore and genomes from 2022 global outbreaks (Figure 1B). Since viruses in this clade have been transmitting from person to person in dozens of countries and potentially over multiple years, we propose that this represents transmission route distinct from that of previous MPXV cases in humans and should be afforded a distinct name so that it can be referred to specifically in both scientific discourse and the general media.

This description is distinctly at odds with the WHO depiction of monkeypox as a zoonosis. It also stands in stark contrast to the CDC’s depiction of monkeypox transmission. Yet the authors are too worried about “stigmatizing” folks in West Africa to explore these variances. A valuable line of inquiry is being effectively discarded.

In addition to being more than just a zoonosis, global monkeypox is now more established outside of Africa than it has been within it. Yet that line of inquiry, including whether there should now be additional clades of monkeypox strains defined, remains almost entirely ignored, squelched by the fear of “stigmatizing” various people and groups.

Is COVID-19 A Factor?

The extent to which COVID-19 complicates a complete understanding of the monkeypox outbreak is an ongoing question for which there has been some discussion.

A chief concern in this regard is the potential for co-infection, and the probability of co-infection to complicate diagnosis and treatment of either viral infection.

It is important to consider the recent spread of monkey pox in the light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and the potential for coinfection between SARS-CoV-2 and the monkeypox virus. This may result in changes related to infectivity patterns, severity, management, or response to vaccination in one or both diseases [9]. That could also negatively impact the efficiency of diagnostic tests used in both diseases [10]. In addition, the interaction between both viruses could facilitate emergence of a new variant of concern (VOC) of SARS-CoV-2 with features that could further impact the current pandemic management strategies, such as increased capability for immune evasion or escape, and burden the health care system as a whole. Nevertheless, the rise in the number of cases of monkeypox is a global concern that needs to be addressed by research and studies [11].

The monkeypox outbreak itself is too recent to have established any research base quantifying these potential problem areas. Still, prior research into co-infection of respiratory viruses and SARS-CoV-2 offers some support for combining treatment protocols.

Other research has noted the potential for viral co-infection to magnify certain symptoms and outcomes.

…hyperinflammation, as well as disorders, such as shock, ARDS, myocarditis, acute kidney injury, and dysfunction of other organs are found in COVID-19 patients with influenza virus coinfection, owing to the stronger and more frequent activation of the cytokine cascade caused by the flu virus infection.

The extent to which these potential complicating factors of viral co-infection exacerbate real-world cases of both monkeypox and SARS-CoV-2 is still the big unknown. Unsurprisingly, where research has touched upon that question, the conclusion has been that viruses must be contained now.

It is too soon to understand if the current monkeypox outbreak is an independent phenomenon, or if it has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This uncertainty calls for precautious actions to be taken by healthcare authorities to contain such outbreaks before the alarm bell starts ringing louder as cases mount and interaction with other infectious agents, not least SARS-CoV-2, leads to emergence of variants of increase pathogenicity.

Apparently, we must not let any virus be allowed to simply virus.

A Concern Is Not A Crisis

People are right to be concerned about monkeypox. We must not forget that monkeypox has claimed lives in Africa, and it is quite remarkable that it has not done so globally. Any disease with the potential to kill should never be taken lightly.

Yet people should also remain grounded in reality. The reality of monkeypox globally is that, in evolving to apparently become more transmissible, it has become considerably less lethal. While it is likely just a matter of time until a monkeypox death is recorded outside of Africa, the fact that such has not happened yet establishes that the new global strain of the virus is far milder than its predecessors.

While we should not dismiss monkeypox simply because it is concentrated within a particular patient demographic (gay and bisexual men), the fact that it is largely concentrated within a singular demographic even where the disease is spreading most must also not be dismissed. Most people outside of that particular demographic are at fairly low risk of catching the disease.

This demographic particularity is not a call to ignore the virus, but it is a call to be sane and prudent in response. Certainly those at elevated risk should be advised on how to protect themselves from the virus, and should the smallpox vaccines prove effective at stopping monkeypox as well, higher-risk individuals should consider the merits and demerits of vaccination.

For everyone outside the high-risk demographics, however, the reality of biological pathogens remains what is has always been: viruses are going to virus. They are going to spread, they are going to mutate, they are going to evolve in ways to maximize their transmissibility and pathogenicity. They may become more virulent. This has been the reality of the world since before the dawn of civilization, and it will be the reality of the world long after our present civilization has collapsed and faded away (as all things made by man invariably do).

Monkeypox is spreading. That makes it a concern. It does not make it a crisis, at least not yet. It certainly does not make it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, nor any other sort of emergency.

In the WHO Disease Outbreak News bulletin of 10 June 2022, it was reported that 72 people had died out of 59 confirmed and 1536 suspected cases of monkeypox in West and Central Africa since the first of the year. In subsequent DON updates, the WHO consolidated that outbreak with the global outbreak, but stopped reporting the suspected cases and dropped the “official” count of monkeypox deaths in the African outbreak to 1. Outside of Africa no deaths have been reported.

The extent to which monkeypox qualifies as a true “Sexually Transmitted Disease” as opposed to one for which infection can be facilitated by intimate sexual contact is itself a bit of a question at this point, with news articles taking both sides of the question. There are, however, studies which have found monkeypox virus in the seminal fluid of infected patients.

"LRN was established in 1999† as a partnership among CDC, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Association of Public Health Laboratories, with the goal of ensuring a laboratory infrastructure across the United States that can respond quickly and effectively to biothreats, chemical threats, and emerging infectious diseases (1). LRN provides the framework to rapidly distribute laboratory diagnostic tests, standardized reagents, and standard operating procedures, and to train laboratory personnel, report laboratory test results, and provide critical communication during routine and emergency responses. LRN includes approximately 110 U.S. laboratories, primarily state and local public health and DOD laboratories, as well as veterinary, food, and environmental testing laboratories. LRN laboratories are required to participate in proficiency testing exercises to ensure competency for laboratory test methods distributed to the network.”

Aden TA, Blevins P, York SW, et al. Rapid Diagnostic Testing for Response to the Monkeypox Outbreak — Laboratory Response Network, United States, May 17–June 30, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:904-907. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7128e1.

This monkey pox issue sound like a set up. I think they over play this disease fearmonger too long for people to trust the media and so call health authorities. My amateur thinking.

"Are You Scared Yet?"

Absolutely not. I don't engage in the sort of behavior that appears to be the primary source of spread, nor do I associate with people who do, or travel to places where it's endemic.