The Fed Is Not The World's Central Banker

The Fed Has Its Sins: Global Consumer Price Inflation Is Not Among Them

Bashing the Federal Reserve has in many circles become something of a perverse pleasure, an almost recreational exercise in economic virtue signalling that pins all the world’s ills on an hopelessly corrupt and compromised Fed, fiendishly wrecking the global economy for…well…reasons.

While the Fed has made more than its share of policy mistakes and missteps, to lay the extreme dysfunction that is the rapidly deglobalizing and contracting world economy all at the Fed’s doorstep is, to put it kindly, absurd. Not that corporate media has ever let small details such as evidence and reason stand in the way of a good narrative, especially one with the mass-market appeal of “It’s all the Fed’s fault.”

The Fed “Exports” Inflation. Yes, Really.

Certainly, that is the narrative that CNN, ever the bastion of honest, objective, fact-based news (not really, they’re still the most busted name in fake news) has chosen.

“We’re seeing the Fed being as aggressive as it has been since the early 1980s. They’re willing to tolerate higher unemployment and a recession,” said Chris Turner, global head of markets at ING. “That’s not good for international growth.”

The Federal Reserve’s decision to raise rates by three-quarters of a percentage point at three consecutive meetings, while signaling more large hikes are on the way, has pushed its counterparts around the world to get tougher, too. If they fall too far behind the Fed, investors could pull money from their financial markets, causing serious disruptions.

Follow the narrative logic here. The Fed takes a stance against inflation and fundamentally in defense of the US dollar and the US economy (whether that stance is effective is another matter), and that is bad for the global economy. One central bank defending its mandate makes that central bank the problem, especially when that central bank is the Federal Reserve.

That rather defeats the point of countries having central banks.

But CNN does not stop there. They immediately take the next narrative step of accusing the Fed of exporting inflation. All the world’s inflation is the handiwork of the clumsy, oafish, misguided Federal Reserve.

The Fed’s stance has also pushed the dollar to two-decade highs against a basket of major currencies. While that’s helpful for Americans who want to go shopping abroad, it’s very bad news for other countries, as the value of the yuan, the yen, the rupee, the euro and the pound tumble, making it more expensive to import essential items like food and fuel. This dynamic — in which the Fed essentially exports inflation — adds pressure on local central banks.

There is just one teeny tiny problem here: global inflation predates the Federal Reserve rate hikes quite literally by months.

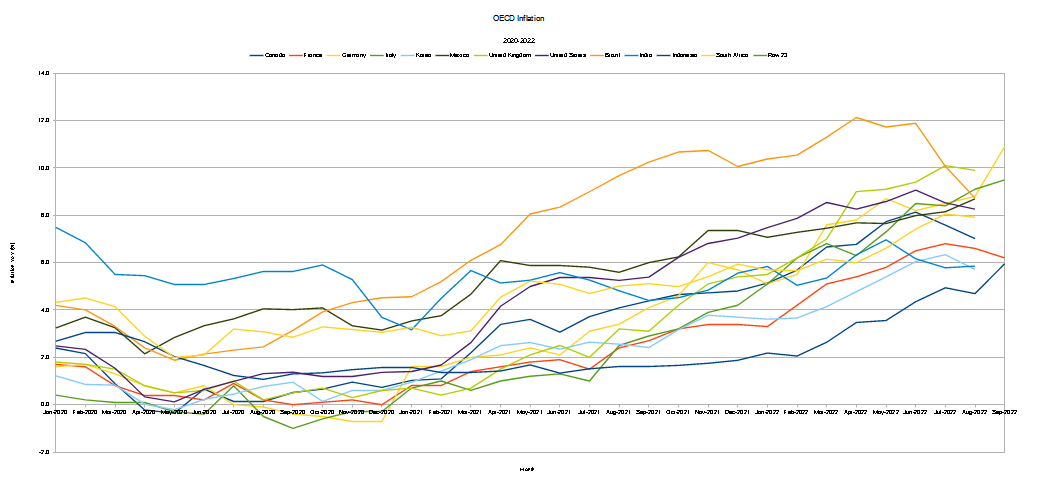

Inflation began taking hold globally at the beginning of 2021, some 13 months before the first Federal Reserve interest rate increase. In fact, for most countries, the bulk of the inflation rise they have experienced occurred before the Fed began raising rates this past March. It is not possible for the Fed to have “exported” global consumer price inflation since January 2021 when it didn’t take the first step on interest rates until March of 2022. Those numbers simply do not line up.

Of course, CNN wouldn’t be the paragon of journalistic incompetence they are without going on to immediately contradict themselves, pointing out that the market instabilities in the UK are the consequence of Liz Truss’ mini-budget (and the market’s lack of confidence therein).

The United Kingdom shows just how quickly the situation can spiral out of control as global investors choked on a new government’s economic growth plan. The British pound fell to a record low against the dollar on Monday after the unorthodox experiment of implementing large tax cuts while boosting borrowing triggered alarm.

If the catalyst in the British pound’s recent decline was the mini-budget, how is the Fed to blame for that?

The UN Weighs In On Rate Hikes And Insists They Stop

Never one to be left out of a good narrative, the United Nations chose this week to weigh in against the idea of central banks raising interest rates.

In its annual report on the global economic outlook, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) said the interest rate increases and austerity policies in wealthy nations represented an "imprudent gamble" that risked backfiring, particularly on lower-income nations.

"There’s still time to step back from the edge of recession," UNCTAD Secretary-General Rebeca Grynspan said. "We have the tools to calm inflation and support all vulnerable groups. But the current course of action is hurting the most vulnerable, especially in developing countries and risks tipping the world into a global recession."

Of course, as the market meltdown last week in the UK confirmed, the world is already in a global recession.

As for interest rate rises targeting or at least impacting “vulnerable” populations around the world, inflation is already doing that.

In all fairness to the UN, they did get one thing right: central banks will contain inflation by triggering a recession.

"Excessive monetary tightening could usher in a period of stagnation and economic instability," the UNCTAD said in a statement accompanying the report. "Any belief that they (central banks) will be able to bring down prices by relying on higher interest rates without generating a recession is, the report suggests, an imprudent gamble."

However, what the UN missed is that recession isn’t just the consequence of the central bank rate hike strategy—it’s the primary objective.

What the UN also fails to realize is that, post-pandemic, the world’s leading economies have been moving along considerably different trajectories, with China using monetary stimulus in an attempt to generate a fresh spark of economic life in their steadily deteriorating economy.

The People's Bank of China has consistently imposed a strong bias to its currency reference rate to help support the yuan. Central bank officials have also issued verbal warnings against speculating on the yuan and increased the cost of shorting the currency.

But it has refrained from raising benchmark rates and instead has been easing them in an effort to spark growth in an economy that's been dragged down by COVID-19 lockdowns, a real estate crash, and supply chain snags.

With their looser monetary policies, the PBOC has sought to address China’s economic woes just as the Fed has sought to address those of the US with tighter monetary policies, an interesting policy divergence I noted at the beginning of the summer would lead to an interesting comparison and contrast of the relative successes and failures of each policy.

We are beginning to see how the two policies of played out, with China’s looser monetary regime having failed to stimulate the Chinese economy, so much so that Beijing is now ordering state-run banks to execute a large “dollar dump”, selling dollars from their forex reserves and buying offshore yuan in an effort to stop the yuan’s depreciation against the dollar.

The amount of dollars to be sold hasn't been decided yet, but Reuters said it will primarily involve the state banks' currency reserves. Their offshore branches, including those based in Hong Kong, New York and London, were ordered to review offshore yuan holdings and check to see that dollar reserves are ready.

As ZeroHedge noted with Japan’s recent experience with market interventions to defend the yen, a “dollar dump” strategy is pretty much guaranteed to fail, as the intervention does not alter any of the market dynamics driving currency depreciation.

The intervention, conducted after the yen slumped to a 24-year low of nearly 146 to the dollar, triggered a sharp bounce of more than 5 yen per dollar from that low, although the currency has since drifted down again to just shy of 145, effectively wiping out most of the intervention, and while the 145 level, viewed as the BOJ's redline has held so far, it is only a matter of time before it is breached again... and again.... at which point Kuroda will capitulate and move his redline to 150 or worse.

There is little reason to expect any better outcome for the yuan. China can sell all its forex reserves, and doing so will never change the market fundamentals weakening the yuan.

Not All The Fed’s Fault

While there is much to criticize about the Fed’s interest rate hikes—and readers of this Substack have already seen the many criticisms I have made about the rate hikes—it is simply ludicrous to foist onto the Fed’s shoulders the central bank mis-steps of the Bank of Japan, the PBOC, or the ECB.

It was the Bank of Japan that refused to raise rates earlier in the year when the Fed began getting serious about the rate hikes.

Central banks around the world are raising interest rates rapidly, except one. The Bank of Japan affirmed Friday that it wanted rates around zero, even if investors are using that as a reason to sell the yen.

“It is not appropriate to tighten monetary policy at this point,” said Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda. “If we raise interest rates, the economy will move into a negative direction.”

This selfsame Kuroda last week was compelled to mount a defense of the yen as the exchange rate plummeted past 146 yen to the dollar.

Similarly, as noted previously, it was the PBOC that opted to pursue a policy of monetary easing and stimulus to address their own contracting economy.

Both central banks—the BoJ in particular—could have taken the matter of policy coordination up with the Fed back then, in an updated version of the 1985 Plaza Accord1 which also attempted to stem a strengthening US dollar and giving other central banks and other currencies room to breathe.

The Plaza Accord was meant to push down the U.S. dollar, with the U.S., Japan, and Germany agreeing to implement certain policy measures to achieve this mission. The U.S. pledged to reduce its federal deficit. Japan and Germany were to boost domestic demand through policies such as implementing tax cuts. All parties agreed to directly intervene in currency markets as necessary to correct current account imbalances.

While the rumors of a new Plaza Accord have occasionally floated around financial markets, the Fed’s stated position on inflation leaves very little room for compromise.

We have been inundated in recent days with questions from clients asking if a repeat is now likely. With global policymakers meeting in mid-October for the IMF meetings in Washington, DC, surely a new Plaza accord is around the corner? Yes, the most important step for any new dollar accord is for the Fed to stop its planned hikes. Without that, nothing will work. But surely Fed officials are willing, given the damage that a strong dollar is now causing elsewhere?

Not a chance. Like Tom Petty, the Fed won’t back down.

However, as BoJ Governor Kuroda made plain back in June, the BoJ position on interest rates also leaves very little room for compromise.

The PBOC, for its part, has always opted to play by its own rules.

Yet, as we have seen with the BoE market intervention last week, as well as the BoJ defense of the yen, and what we will likely see from the PBOC defense of the yuan, there are network effects to every central bank move. Currency by its very nature is fluid, and monetary policy consequently almost never remains within a nation’s borders. What happens on Wall Street will never stay just on Wall Street.

Thus the question becomes—what are the global obligations of the world’s central banks to each other and to the overall world economy? Are there any obligations at all?

Certainly, outside a formal arrangement such as the Plaza Accords, central banks have no formal obligation to focus on anything but their own currency, their own interest rates, and their own monetary policies.

The reality is that central banks have always hewed to their own policy priorities, and have responded to the policy moves of other central banks only as those moves affected them. Central banks do not compare notes and do not, as a rule, coordinate their monetary policies.

Right or wrong, good or bad, the Fed opted to tackle consumer price inflation with the same rate hike strategy deployed by Paul Volcker in 1979. In this regard, the Fed had the good fortune to be first. The other central banks have always been faced with the same policy choices: follow along or take an independent tack. The ECB and the BoE followed along; the PBOC and the BoJ chose an independent path.

Yet no central bank—not the Fed, not the BoE, not the ECB, and certainly not the PBOC or the BoJ—has been able to fend off the recession that has spread across the globe almost as fast as COVID did in 2020. Which underscores the real problem among the world’s central banks: none of them have any real clue what they should be doing, either for their respective economies or the global economy as a whole.

Chen, J. Plaza Accord Definition. 25 July 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/plaza-accord.asp.

Perhaps the Fed has not been exporting inflation directly, but the USA certainly has. Trillions of dollars have left the country due to our staggering trade deficits. When they're not here, they don't contribute to inflation here.