The Fed Maintains Current Rates And STILL Wall Street Freaks Out

When Jay Powell Opened His Mouth Was When Markets Started Heading South

Officially, the Federal Open Market Committee decided against raising the federal funds rate another 25bps at yesterday’s conclusion of their September meeting.

The US Federal Reserve System acting as the national central bank left the base interest rate at 5.25-5.5% following its September meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) reported.

"The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2% over the longer run. In support of these goals, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5-1/4 to 5-1/2%," the statement reads.

Unofficially, Jay Powell managed to raise the 10 Year Treasury yield 12bps while sapping over 270 points from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, just by holding the post-meeting press conference. With his chronic case of foot in mouth disease, Powell managed to do what the FOMC has struggled to do: push actual yields up yet again.

Who needs federal funds rate hikes when Jay Powell just has to speak to send markets spiraling?

Jay Powell’s impact on Wall Street was almost instantaneous.

As soon as the FOMC released its post-meeting press release, the Dow Jones index, which had been up 205 points on the day, dropped over 120 points in the space of about 7 minutes.

At the same time stocks were plummeting, bond yields were spiking.

The 10-Year Treasury yield jumped 3 basis points between 2PM and 2:05PM Eastern Time.

The 10-Year Treasury would end up the day rising over 12bps from its 2PM level.

The 2-Year Treasury yield jumped 9bps at almost the same time, on its way to a 12bps rise from its 2PM level.

The 1-Year Treasury only rose 6bps between 2PM and 2:05PM.

Only in forex markets did the dollar do well, rising against the euro, the pound sterling, and the yen.

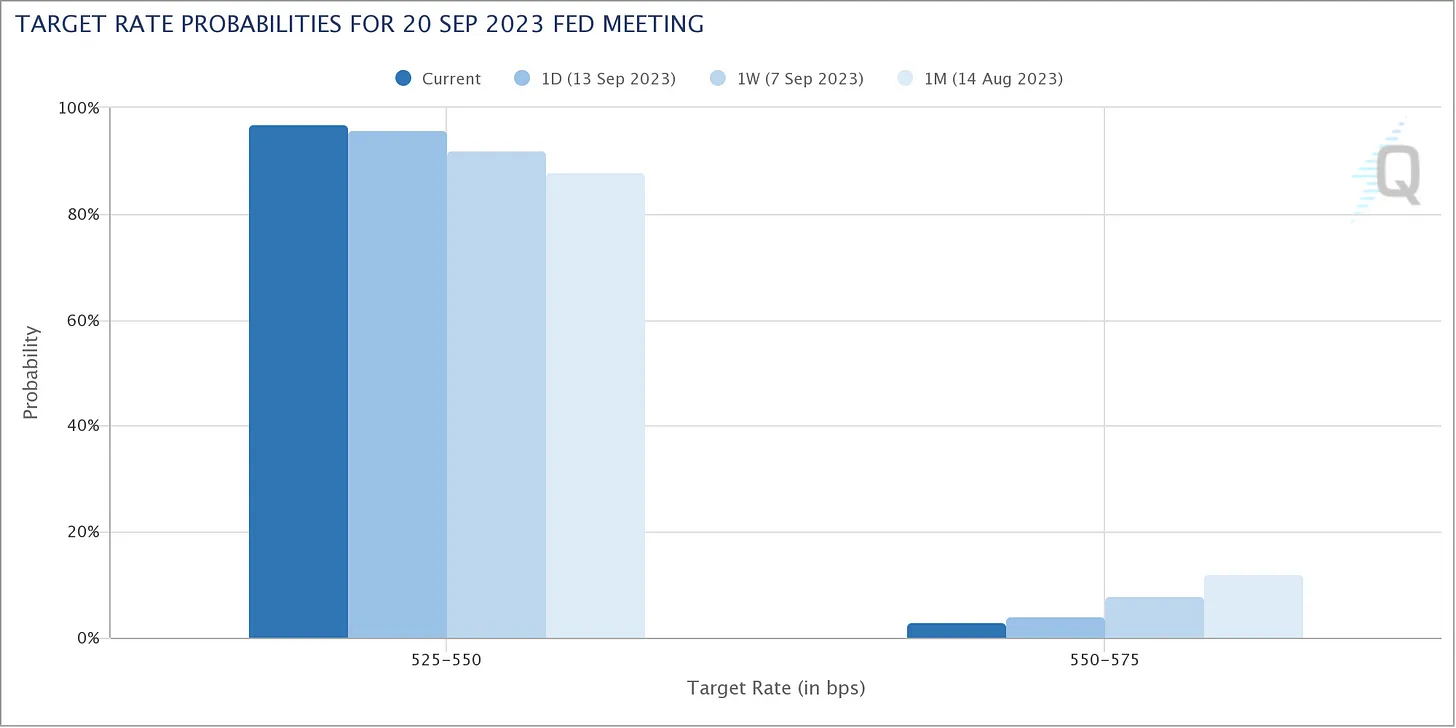

What makes this flurry of market panic ironic is that Wall Street had by last week fully priced in the possible consequences of the FOMC standing pat on the federal funds rate.

Wall Street had already figured out what was going to happen—and yet Jay Powell still managed to spook the markets. How did he manage to do this?

Mostly, the FOMC confirmed yet again that, while it is not raising rates right now, it all but committed to at least one more federal funds rate hike during calendar 2023 (emphasis mine).

In determining the extent of additional policy firming that may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans. The Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.

Powell doubled down on this position in his opening remarks at the post-meeting press conference.

If the economy evolves as projected the median participant projects that the appropriate level of the federal-funds rate will be 5.6 percent at the end of this year, 5.1 percent at the end of 2024, and 3.9 percent at the end of 2025. Compared with our June Summary of Economic Projections, the median projection is unrevised for the end of this year but is moved up by a half percentage point at the end of the next two years.

Right out of the gate, the media tried to pin Powell down on whether there would be additional rate hikes, without getting much that was of comfort to Wall Street.

Q: Thank you. Colby Smith with the Financial Times.

What makes the committee inclined to think that the fed-funds rate at this level is not yet sufficiently restrictive, especially when officials are forecasting a slightly more benign inflation outlook for this year? There’s noted uncertainty about policy lags. Headwinds have emerged from the looming government shutdown, the end of federal childcare funding, resumption of student debt payments, things of that nature.

MR. POWELL: So I guess I would characterize the situation a little bit differently. So we decided to maintain the target range for the federal-funds rate where it is at 5 ¼ to 5 ½ percent while continuing to reduce our securities holdings, and we say we’re committed to achieving and sustaining a stance of monetary policy that’s sufficiently restrictive to bring down inflation to 2 percent over time. We said that.

But the fact that we decided to maintain the policy rate at this meeting doesn’t mean that we’ve decided that we have or have not at this time reached that stance of monetary policy that we’re seeking. If you looked at the SEP, as you obviously will have done, you will see that a majority of participants believe that it is more likely than not that we will—that it will be appropriate for us to raise rates one more time in the two remaining meetings this year. Others believe that we have already reached that. So it’s something where we’re – we’re not making a decision by deciding to—about that question by deciding to just maintain the rate and await further data.

Q: So right now it’s still an open question about sufficiently restrictive. You’re not saying today that we’ve reached this level.

MR. POWELL: We’re not saying—no. Clearly, we are just—what we’ve decided to do is maintain the policy rate and await further data. We want to see convincing evidence, really, that we have reached the appropriate level. And then, you know, we’ve seen progress and we welcome that. But, you know, we need to see more progress before we’ll be willing to reach that conclusion.

There is, of course, a delicious irony in Wall Street’s discomfiture over Powell’s all but promising more rate hikes. After all, Powell has repeatedly indicated that he would happily throw Wall Street under the recession bus to make his interest rate strategy work. We should remember that was the core message of his 2022 Jackson Hole speech, which had substantially the same reaction from Wall Street as today.

It took Wall Street less than 30 minutes after Powell finished speaking to surrender their stock market gains for the week. By 10:30 Eastern Time the Dow Jones Industrial Average was down 2.3% on the day. After a brief attempt at a rally just after lunchtime, the stock markets fell even further, with the DJIA down 4.2% on the day, the NASDAQ down 4.4%, and the S&P 500 down 4% on the day. The Russell 2000 small-cap index fared the best, “only” losing 2.9% on the day.

What Wall Street likely found particularly upsetting was the Fed’s apparent comfort with keeping interest rates high indefinitely.

Q: Steve Liesman, CNBC.

Mr. Chairman, I want to return to Colby’s question here. What is it saying about the committee’s view of the inflation dynamic in the economy that you achieve the same forecast inflation rate for next year, but need another half a point of the funds rate on it? Does it tell you that—does tell us that the committee believes inflation to be more persistent, requires more medicine, effectively? And I guess a related question is, if you’re going to project a funds rate above the longer-run rate for four years in a row, at what point do we start to think, hey, maybe the longer rate or the neutral rate is actually higher? Thank you.

MR. POWELL: So I guess I would point more to—rather than pointing to a sense of inflation having become more persistent, I wouldn’t think—that’s not—we’ve seen inflation be more persistent over the course of the past year. But I wouldn’t say that’s something that’s appeared in the recent data. It’s more about stronger economic activity, I would say. So if I had to attribute one thing. Again, we’re picking medians here and trying to attribute one explanation. But I think broadly, stronger economic activity means rates—we have to do more with rates. And that’s what that that’s what that—that’s what that meeting is telling you.

In terms of what the neutral rate can be, you know, we know it by its works. We only know it by its works, really. We can’t—we can’t—you know, the models and—that we use, ultimately, you only know when you get there and by the way the economy reacts. And again, that’s another reason why we’re moving carefully now, because, you know, there are lags here. So it may—it may, of course, be that the neutral rate has risen. You do see people—you don’t see the median moving, but you do see people raising their estimates of the neutral rate. And it’s certainly plausible that the neutral rate is higher than the longer-run rate. Remember, what we write down in the SEP is the longer-run rate. It is certainly possible that—you know, that the neutral rate at this moment is higher than that. And that’s part of the explanation for why the economy has been more resilient than expected.

By suggesting that the “neutral” interest rate (the interest rate which neither stimulates nor hinders economic growth) was in fact higher than Wall Street has previously surmised, Powell is intimating that higher interest rates might even be here to stay. This was not a message Wall Street wanted to hear.

Equally distressing to Wall Street was undoubtedly the Fed’s seeming nonchalance about the prospects for a recession rather than a “soft landing” for the US economy.

Q: So just to boil that down for a second, you know, we’ve gone from a very narrow path to a—to a soft landing to something different. Would you call the soft landing now a baseline expectation?

MR. POWELL: No. No, I would not do that. I would just say—what would I say about that? I’ve always thought that the soft landing was a plausible outcome; that there was a path, really, to a soft landing. I’ve thought that and I’ve said that since we lifted off. It’s also possible that—the path has narrowed and it’s widened, apparently. Ultimately, this may be decided by factors that are—that are outside our control, at the end of the day. But I do think it’s—I do think it’s possible.

And you know, I also think, you know, this is why we are in a position to move carefully, again, that we will restore price stability. We know that we have to do that and we know the public depends on us doing that. And we know that we have to do it so that we can achieve the kind of labor market that we all want to achieve, which is an extended period, sustained period of strong labor market conditions that benefit all. We know that. The fact that we’ve come this far let us really proceed carefully, as I keep saying.

So I think, you know, that’s the end we’re trying to achieve. I wouldn’t want to handicap the likelihood of it, though. It’s not up to me to do that.

On this score, Powell would end up talking out of both sides of his mouth—first being dismissive of the soft landing scenario than saying that achieving the soft landing was a priority for the Fed.

Q: Craig Torres from Bloomberg News.

I was a little surprised, Chair Powell, to hear you say that a soft landing is not a primary objective. This economy is seeing added supply in a way that could create long-term inflation stability. We have prime age labor force participation moving up, where people can add skills. Workers want to work. We have a boom in manufacturing construction. We’ve had a decent spate of homebuilding. And since inflation’s coming down with strong GDP growth, we may have higher productivity. All are good for the Fed’s longer run target of low inflation. And if we lose that in a recession, aren’t we opting for the awful hysteresis that we had in 2010? So are you taking this into account as you pursue policy? Thank you.

MR. POWELL: To begin, a soft landing is a primary objective. And I did not say otherwise. I mean, that’s what we’ve been trying to achieve for all this time. The real point, though, is the worst thing we can do is to fail to restore price stability, because the record is clear on that. If you don’t restore price stability, inflation comes back and you go through—you can have a long period where the economy is just very uncertain. And it’ll affect growth. It’ll affect all kinds of things. It can be a miserable period to have inflation constantly coming back, and the Fed coming in and having to tighten again and again.

So the best thing we can do for everyone, we believe, is to restore price stability. I think now, today, we actually—you know, we have the ability to be careful at this point and move carefully. And that’s what we’re planning to do. So we fully appreciate that—you know, the benefits of being able to continue what we see already, which is rebalancing in the labor market and inflation coming down, without seeing, you know, an important—a large increase in unemployment, which has been typical of other tightening cycles, so.

So to summarize: a soft landing for the US economy is a primary objective for the Federal Reserve but the Fed will not say in any way whether it is likely to succeed, more than a year and a half of rises in the federal funds rate. There might not be a recession, or there might be a recession.

Yeah, that makes sense.

Even on oil prices, which have been rising of late, Powell had little comfort to offer, both dismissing oil prices as being relevant to his rate hike strategy as well as being outside the scope of what rate hikes can hope to accomplish.

Q: Thanks for the question, Chair Powell. Edward Lawrence with Fox Business.

So I want to focus back in on oil prices. We’re seeing oil prices, as you mentioned, move up and that’s pushing the price of gas. So how does that factor into your decision to raise rates or not? Because the last two inflation reports, PCE and CPI, we’ve seen that overall inflation has actually risen.

MR. POWELL: Right. So, you know, energy prices are very important for the consumer. This can affect consumer spending. It certainly can affect consumer sentiment. I mean, gas prices are one of the big things that affects consumer sentiment. It really comes down to how persistent, how sustained these energy prices are. The reason why we look at core inflation, which excludes food and energy, is that energy goes up and down like that. And it doesn’t—energy prices mostly don’t contain much of a signal about how tight the economy is and, hence, don’t tell you much about where inflation is really going. However, we’re well aware, though, that—you know, if energy prices increase and stay high, that’ll have an effect on spending. And it may have an effect on consumer expectations of inflation, things like that. That’s just things that we have to monitor, so—

Translation: Jay Powell just doesn’t give a damn about energy prices, he just can’t say that out loud.

What was even more disconcerting, however, is Powell’s seeming belief that energy prices do not have much to do with inflation. Given that inflation’s recent resurgence in this country has been powered by energy prices, Powell’s assertion is a staggering bit of ignorance about the real-world economic data.

Nor was Powell particularly impressive on the follow-up question regarding consumer credit.

Q: On the consumer, they’re putting more and more of this on their credit card. The consumer’s seeing, you know, record credit spending. How long do you think the consumer can manage that debt at higher interest rates now? And are you concerned about it a debt bubble related to that?

MR. POWELL: So, to finish my prior thought, I was saying that’s why we tend to look through energy moves that we can see as short-term volatility.

You know, turning to consumer credit, you know, of course, we watch that carefully. Consumer distress—measures of distress among consumers were at historic lows quite recently, you know, after—during and after the pandemic. They’re now moving back up to normal. We’re watching that carefully. But at this point, these readings are not—they’re not at troublingly high levels. They’re just kind of moving back up to what was typical in the pre-pandemic era.

While credit card delinquency rates did drop to a surpring law in the immediate aftermath of the COVID faux pandemic, as of the second quarter they are higher than they were before the pandemic and the Pandemic Panic Recession.

Nothing says “I don’t give a damn about consumers” quite like not knowing how far credit card delinquency rates have risen.

And so it went. Corporate media asked questions, Powell gave answers, Wall Street said “WTF????” before hitting the “sell” button on their collective stock trading apps.

Much like Powell’s 2022 Jackson Hole speech, yesterday’s FOMC presser was Jay Powell telling Wall Street he’s going to do as he damn well pleases on interest rates because…reasons.

Even Wall Street bond and interest rate maven Mohammed El-Erian was nonplussed, who somewhat charitably described Powell’s performance as “confused and confusing.”

In addition to “confused” and “confusing”, we should also add “contradictory”.

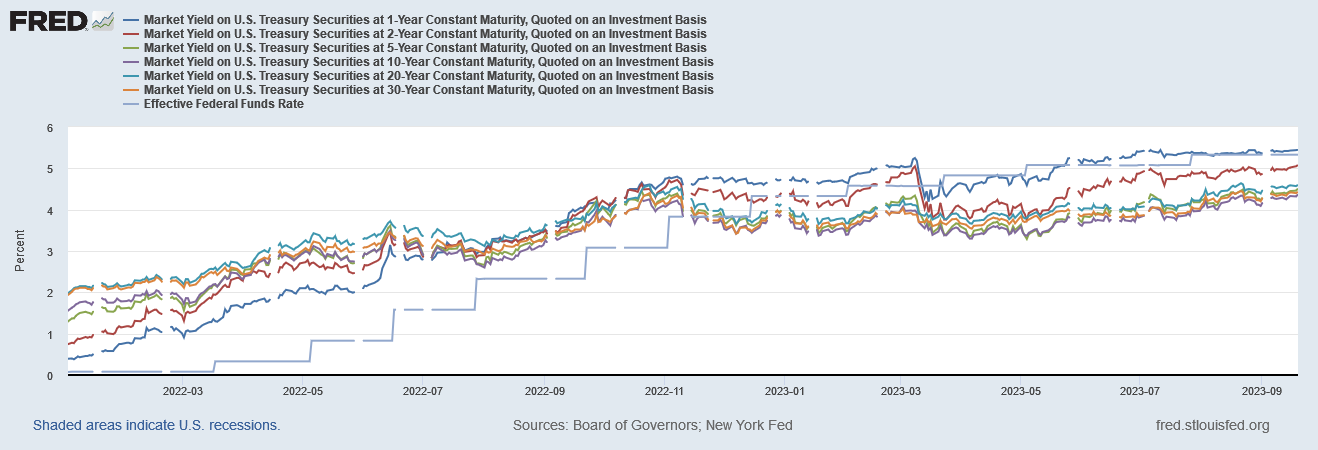

Powell proposed that the neutral rate is actually higher than the currently projected longer-run rate, which the FOMC pegs at 2.5%.

What is particularly discordant about both Powell’s proposal and the FOMC’s longer-run projections is that both are higher than what the Federal Reserve itself calculates as the “natural” rate of interest—that interest rate which prevails when inflation is under control and the economy is at full throttle. As of the latest calculations at the New York Fed, the natural rate of interest is 1.14%.

Nominal treasury yields across the yield curve are well above this calculated natural rate.

Thanks to inflation, actual real yields are below the natural rate on the long end of the yield curve, with only the 2-Year Treasury yield at the natural rate of interest.

If Powell is to be believed (key word: “if”), both the natural and the neutral rates of interest need to come up significantly—which would be a permanent paradigm shift in Wall Street financial models. Powell spoke to none of the ramifications of this shift to permanently higher interest rates.

The most significant ramification of what Powell was suggesting is that, if interest rates shift permanently higher, almost all ETF holdings of current Treasuries, with their outdated low yields, will lose far more value than they have lost already, thanks to Powell’s federal funds rate hikes.

Suffice it to say, the impact of this on bank balance sheets would be worse than the balance sheet erosion which contributed to the mini-banking crisis this past spring.

Powell’s problem, of course, is that the current rising inflation trend indicates that his interest rate strategy is about to come completely off the rails.

What lies ahead is consumer price inflation that will completely ignore the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate hikes intended to push up market interest rates broadly, punctuating the Fed’s complete failure to corral and reduce inflation. Get used to higher inflation—it’s going to be with us a while.

Powell may enjoy ignoring energy price inflation, but the reality is that it also tends to ignore him. The reality is also that Wall Street cannot ignore Powell’s erosion of their securities portfolios. As it is he has already peeled off over 10% of the portfolios’ overall value. If those portfolios continue to shed value it will not take much for another banking and liquidity crisis to emerge.

Small wonder Treasuries became less attractive and the price dropped (yields move in opposition to bond prices, so when yields rise the price drops). Even smaller wonder that stock markets also dropped. With Powell so clearly not in control even of interest rates, now is the time to either take profits or curb losses, and Wall Street’s money management types did exactly that.

Wall Street seems to be beginning to realize that Powell has painted the Federal Reserve into a corner where it cannot lower rates so long as inflation is above 2%, even though higher energy prices suggest that inflation is becoming structurally higher than before, and thus impervious to all interest rate strategies. If Powell understands this, he hides it well.

Powell was and is confused and confusing on interest rates. Powell is being contradictory on the impacts of interest rates. What Powell is not is being clear on where the Fed will take interest rates next.

This is so not going to end well….

What are our options, for getting rid of him?

Heart attack, stroke, serious cancer condition, or assassination?

Can you comment on this?

https://youtu.be/x_rm3tFXIxk?feature=shared