Why Is First Republic Still Strugging?

The $30 Billion From Dimon's Eleven Didn't Change The Fundamentals

As I concluded after Dimon’s Eleven “graciously” deposited $30 Billion in First Republic Bank for 120 days, the deposits gave the bank a 120-day lease on life, but little more.

For now, First Republic at least as a new 120-day lease on life. Whether that will be sufficient to bring anxiety levels in the US banking sector down to a level resembling “normalcy” remains to be seen.

This past weekend, it would appear that US banking regulators belatedly reached the same conclusion, as they huddled in emergency session to figure out how to extend that time and bring this banking crisis to an end.

US authorities are considering expanding an emergency lending facility for banks in ways that would give First Republic Bank more time to shore up its balance sheet, according to people with knowledge of the situation.

Officials have yet to decide on what support they could provide First Republic, if any, and an expansion of the Federal Reserve’s offering is one of several options being weighed at this early stage. Regulators continue to grapple with two other failed lenders — Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank — that require more immediate attention.

All of which begs the question: what exactly is wrong with First Republic’s balance sheet that it finds itself in such parlous circumstances?

The short answer to that question, amazingly enough, is “not much.”

On paper, First Republic Bank is decently and even somewhat conservatively run. If we look at the FY2022 10-K statement, we see that its capital ratios appear to be well above the 6% minimum.

While there is an uncomfortable unrealized loss within its held-to-maturity securities portfolio, that portfolio is not comprised primarily of US Treasuries, despite what the narrative suggests. The largest securities component is tax-exempt municipal bonds.

Even its loan portfolio is primarily single-dwelling mortgages.

The biggest problem First Republic has is the size of its uninsured deposit base (emphasis mine).

We obtain funds from depositors by offering consumer and business checking, money market and passbook accounts, and term CDs. Our accounts are federally insured by the FDIC up to the maximum limit. At December 31, 2022, our total deposits were $176.4 billion, a 13% increase from $156.3 billion at December 31, 2021, as we continued to expand relationships with existing clients and acquire new deposit clients, both business and consumer. However, our total deposits grew at a slower rate in 2022 than 2021. Refer to “—Financial Highlights—Deposits and Funding” for additional discussion of our deposit funding. Estimated uninsured deposits totaled $119.5 billion and $116.7 billion as of December 31, 2022 and 2021, respectively. Estimates of uninsured deposits are based on the methodologies and assumptions used in our Consolidated Reports of Condition

and Income (“Call Report”) filings.

$119.5 Billion out of $176.4 Billion in total deposits means 67.7% of their deposits are uninsured. Not the staggering 90%+ of Silicon Valley Bank, but still quite high, high enough—referring once again to Erica Jiang’s research1 into the impact of monetary tightening on banks with high ratios of uninsured deposits—that jittery depositors can start a major bank run and batter the bank into failure.

However, outside of that bank run scenario, if the bank’s balance sheet were largely left alone, First Republic likely would have more than a 120-day lease on life.

So why doesn’t it?

The summary reason why First Republic is under duress boils down to the simple reality that its FY2022 10-K balance sheet is simply no longer accurate. In 2023 there has been significant deterioration in fair market value among several types of marketable securities, and all of these come home to roost at First Republic.

Thus what appears to be a respectable portfolio of assets on the FY2022 balance sheet are, by this juncture, somewhat impaired.

Why are these assets impaired? Because the debt securities and the loans have all lost market value—and had been losing market value for quite some time, extending back into 2021.

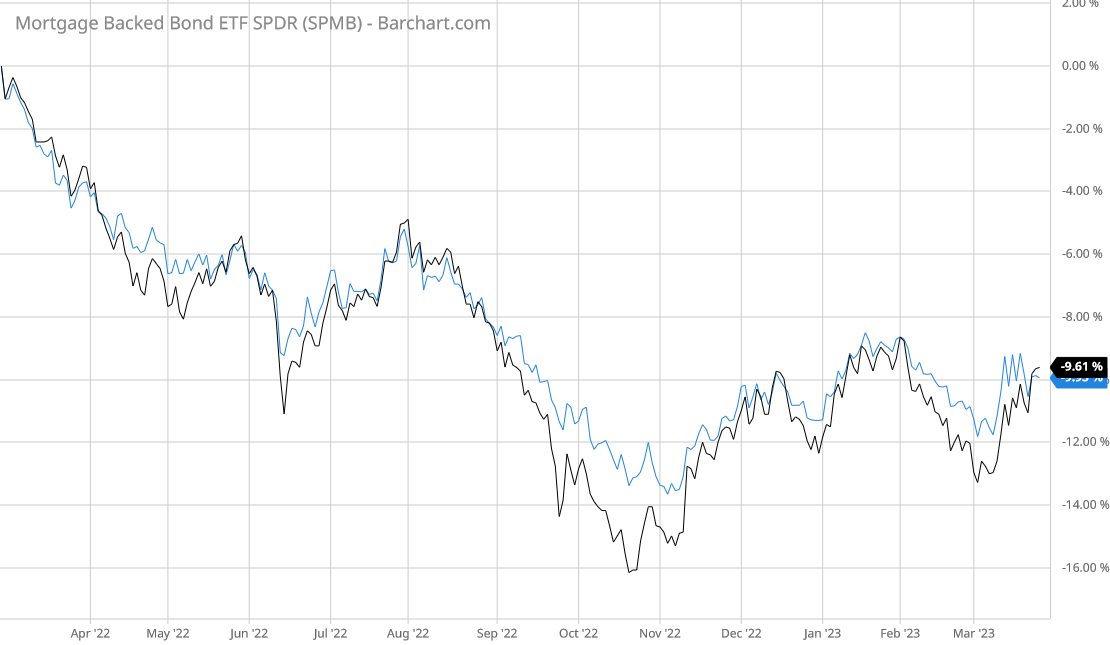

We can presume this to be the case by looking at the performance of various exchange traded funds specializing in mortgage-backed securities and US Treasuries, to give us an approximate view of the shift in the market value of First Republic’s assets.

If we look at the SPDR Mortgage Backed Bond ETF, and its commercial cousin the CMBS, we can see that both funds lost between 6.5%-7.5% between January 2021 and February 2022—right before the Federal Reserve began increasing the federal funds rate.

Those are significant declines that precede the Fed’s interest rate hikes, and the declines since then are even larger at 9.6%.

As First Republic’s loan portfolio is heavy on real estate mortgages, we may fairly assume that the market value of its loan portfolio has grown or shrunk in line with the valuation shifts for these ETFs. These funds lost over 14% of market value in 2022, which means that, if First Republic is compelled to sell its loan portfolio, it can expect a haircut of potentially 14-15%.

While the funds have risen about a percentage point in value since, there is still a substantial probability that, in a fire sale of the bank’s loan portfolio, it would only realize at most 85% of the value of the loans on the books.

The held-to-maturity securities already have an established fair market value some $5 Billion below the amount carried on the books.

When we adjust the value of the loan portfolio for a potential 15% loss, and the HTM investment portfolio for the $5 Billion unrealized loss, the possibility arises that First Republic does not have all the assets it needs to cover deposits. A pro-forma restatement of the essential numbers shows that First Republic comes up just shy of adequate coverage.

If we take away the $30 Billion from Dimon’s Eleven, the coverage ratio gets even worse. However, even at 97%-98%, the end result is still the same: inadequate cash or access to cash to service all depositors. That 2% shortfall is more than enough to start a bank run, as no uninsured depositor wants to be caught in the middle of that 2% shortfall—that was one of the conclusions of Dr. Jiang’s research.

While the $30 Billion Dimon’s Eleven deposited with First Republic was a dramatic vote of confidence, that vote of confidence did not alter the balance sheet dynamics which show that, under conditions of deposit duress, First Republic not only does not have enough cash to satisfy depositor demands, it does not have enough unimpaired assets, period, to satisfy depositor demands. Under fire sale conditions assets which have not had mark downs to fair market value likely would have significant mark downs, and that is enough to leave the bank ultimately insolvent.

The perverse irony, of course, is that the bank run scenario is what forces the asset fire sales in the first place, and magnifies the asset losses that push the bank into insolvency and failure. Depositors are quite literally creating a self-fulfilling prophecy at First Republic.

Yet, even though First Republic’s balance sheet has a fair market value problem, the banking system as a whole has a much larger fair market value problem—deposits have been getting pulled from banks for months. Deposit flight did not begin with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, it merely reached an inflection point for SVB.

If we index to January, 2022, the total deposits at large domestically chartered banks2, small domestically chartered banks, all domestically charted banks, and foreign institutions, we quickly see that declining deposits are a phenomenon everywhere but at foreign institutions.

Aside from financial institutions, however, the larger banks have had worse deposit decline than the small institutions, with the gap getting progressively wider over time.

It should be noted that Silicon Valley Bank was the 16th largest bank in the US at the time it failed, and thus is part of the large domestically chartered bank grouping here. According to Bankrate.com, First Republic is the 14th largest bank in the US, and thus part of that same grouping.

Among the domestically chartered banks, we can see exactly when the deposit decline began—the reporting period ending April 13, 2022, or almost exactly one month after the first federal funds rate increase. If we reset the index to that date, we can better see the magnitude of deposit decline among larger banks vs smaller ones, and across the banking industry in the US overall.

At every time scale, large bank deposit decline outpaces small bank deposit decline, not just relatively speaking, but also in absolute terms, which we can plainly see to be the case throughout the start of 2023 up until the past week.

Remember, First Republic is the 14th largest bank in the US. Whatever deposit decline it is experiencing is being experienced across the other large banks, including the eleven banks which deposited $30 Billion into First Republic as a vote of confidence.

The past week has seen deposits flow from small banks into large banks—ironically catalyzed almost certainly by the Silicon Valley Bank failure, which was a failure of a larger bank rather than a smaller one.

The panic surrounding banks in the markets is also accompanied by outflows from smaller banks. According to new data from the Federal Reserve, Americans withdrew $120 billion in deposits from small banks during the week ending March 15.

The larger banks are undoubtedly seen as “safer” by the average depositor.

The big banks appear to be the big winners of this banking crisis, since they have recorded inflows. Deposits with major banks totaled $10.74 trillion in the week ended March 15, up $67.4 billion. The previous week, i.e. before the collapse of SVB, deposits had fallen by $76 billion with major banks.

Yet, as we can see—as we have seen—the larger banks are not only not safer, they are demonstrably riskier, because depositors are pulling more money out of large banks and have been for some time. Silicon Valley Bank was a large bank. First Republic is a large bank. Depositors are moving their money in the exact opposite direction of the true “flight to safety.”

Wall Street, of course, and the banks, have been aware of this dynamic for quite some time, just as they have been aware of the deteriorating market values of their securities and loan portfolios. Banks are thus put under capital stress because as deposits are pulled from a bank, the bank has to liquidate more and more of its portfolios—at fire sale prices—to cover the deposit outflows.

We must pause at this point to remember that the securities and loan portfolios among banks are not, by and large, “toxic” from the perspective of default risk. With the obvious exception of credit card debt, most consumers and businesses are staying current on their outstanding loan obligations.

Overall, default risk has not risen for these classes of assets. The decline in market value for these asset classes is almost entirely due to the rising interest rate environment brought on by the Fed’s rate hikes on the federal funds rate.

But for the rising interest rate environment, First Republic Bank’s balance sheet would look pretty good, and there would be no drain on deposits. Silicon Valley Bank was largely in the same position, albeit with greater exposure to uninsured (and thus more jittery) depositors.

Because of the rising interest rate environment, however, First Republic Bank is not only not the only bank suffering deposit distress, and because of the rising interest rate environment, the rest of the larger banks including Dimon’s Eleven are experiencing the worst deposit distress. What is happening at First Republic will soon be happening with them, regardless of what happens with smaller banks.

No matter what happens to First Republic Bank in the coming days and weeks, as it grapples with the realities of fair market valuations for its assets, what should worry the regulators especially is that other banks are facing even bigger struggles over those same realities, and have as few options as First Republic with which too address those realities.

Ultimately, the problem for bank regulators is not First Republic Bank, but all the banks behind First Republic, especially the larger banks such as the eleven which ponied up $30 Billion to deposit into accounts with First Republic. The balance sheet woes First Republic has today will be the balance sheet woes they have tomorrow.

Jiang, E., et al. “Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs?” SSRN, 2023, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4387676.

The Federal Reserve defines “large domestically chartered commercial bank” as one of the 25 largest banks by total assets as of the latest FDIC call report. The small domestically chartered commercial banks are all other domestically chartered commercial banks.

This raises so many questions in my mind. *You* are able to see that the balance sheet problems and uninsured deposits of First Republic will inevitably become the problems of the other banks - but to what extent do *they* grasp that? Do they all see that their own bank has a big problem, or, in reassuring their clients, do they talk themselves into believing that it will all be okay somehow (I.e. the government will bail them out)?

How did banks such as Silicon Valley get to a point of having 90% uninsured deposits? Are their risk management officers incredibly incompetent, or were they trying to get away with something, and are there no check measurements in place to prevent this?

The banks in trouble have uninsured deposits at levels of 67-90%, and as interest rates rise, other banks will get into the danger zone, too. What is the historical average level of uninsured deposits, or the level at which finance professionals regard as acceptable? Is this figure widely agreed upon in the industry, leading bank management to take drastic fire-sale measures before their own bank reaches it?

Please don’t feel you have to answer my questions directly, Mr. Kust; it’s just fodder for your future columns...

As I understand it, many of Silicon Valley Bank’s clients were tech companies, who should have had finance professionals handling the dough for the company. Since even *I* know that deposits are only insured up to $250,000, how could these finance professionals make such a stupid mistake?