Recently celebrity investor and star of the reality show “Shark Tank” has joined those in the financial chattering class with a gloom and doom prophecy of a financial apocalypse in commercial real estate for the United States.

In an appearance on FOX Business' "Varney & Co," O'Leary voiced his concerns — that stocks are beginning to plummet in the industry — and claims the business has become "uneconomic" due to inflation and raising debt ceilings.

"It's getting worse by the week, and lots of private equity firms are admitting there's cracks in the system," he said bluntly. "It's based on debt … The debt was raised for these buildings back at 3, 4 and 5%, now they're dealing with 9 to 14% and refinancing them."

O’Leary is not alone. Approximately two-thirds of respondents in a Bloomberg survey agree with him.

Around two-thirds of those who responded to a Bloomberg News survey said they believe that the commercial real estate market will recover only after a crash.

However, despite the very real and worsening financial woes within the CRE sector, there is a potentially far greater concern that would arise from a market crash in commercial real estate: thanks to the financial stresses brought on by the Fed’s failed interest rate strategy to combat inflation, a number of banks may lack the liquidity depth to withstand a complete collapse of commercial real estate values.

Kevin O’Leary’s thesis on a coming apocalypse in commercial real estate is based on a simple observation: as interest rates rise, so to does the cost of refinancing loans as they mature—and interest rates have ballooned relative to where they were before the 2020 Pandemic Panic Recession.

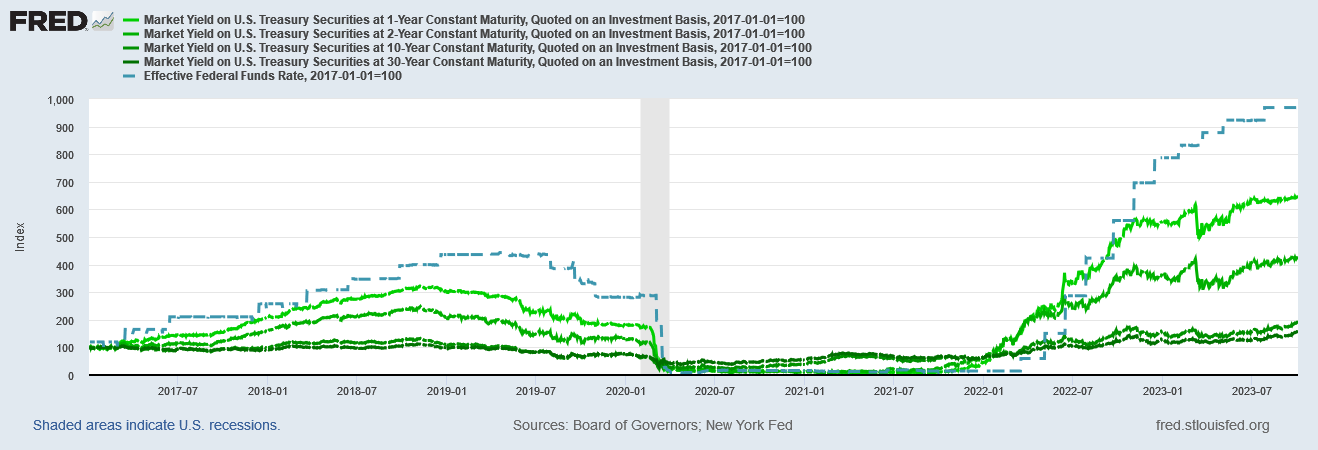

Treasury yields are running more than double than their pre-pandemic peak.

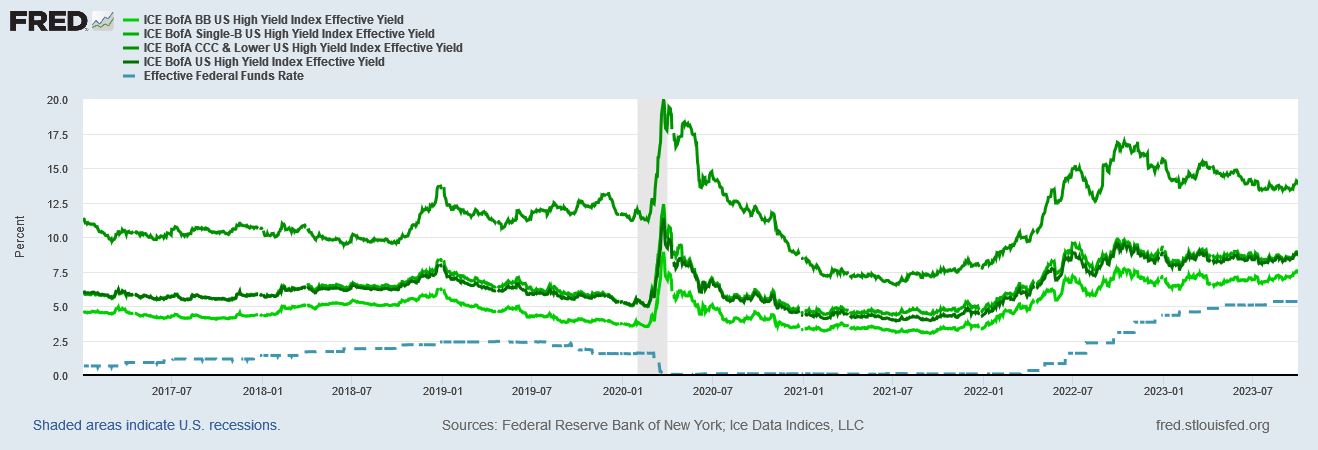

While high-yield corporate bonds (i.e., “junk bonds”) have not seen a doubling of their yields, their yields have also risen considerably from pre-pandemic levels.

Put simply, interest rates are higher across the board.

It’s not hard to fathom why interest rates pose a major problem for the commercial real estate sector: high interest rates mean borrowed money and credit are considerably more expensive than before. When there’s a lot of debt that has to be refinanced, a major increase in the cost of that debt quickly becomes a fairly large problem.

There are literally hundreds of billions of dollars of CRE debt maturing by the end of 2025, all of which was incurred at a time when interest rates were much lower.

Investors are bracing for a possible crisis triggered by default on $1.5 trillion in debt that is coming due by the end of 2025,.

Some $270 billion in commercial real estate loans held by banks are set to mature in 2023, according to Trepp.

Over the next four years, commercial real estate properties must pay off debt maturities that will peak at $550 billion in 2027, according to analysts at Morgan Stanley.

Moreover, it is a problem that is still developing, given that commercial real estate loans are still being made in this country.

One way to gauge the magnitude of the financing challenge posed by rising interest rates is to consider how much debt yields have risen relative to where they were initially. If we index corporate bond yields to January of 2017, for example—a period well before the Pandemic Panic Recession—we see that, as of the beginning of October, 2023, yields on corporate high-yield bonds are roughly 50% higher than they were.

In other words, corporate debt costs the debtor 50% more today than in 2017.

Treasury yields are even more dramatic. The 30-Year Treasury yield has risen 61.8% since January 2017. Shorter maturities, such as the 10-Year Treasury, have practically doubled, and 1-Year and 2-Year Treasuries have risen by multiple orders of magnitude.

The shorter term maturities have seen even larger relative increases. Compared to the rate that held sway at the beginning of January, 2017, the 1-Month Treasury yield has risen nearly 1,260%, with the 3-Month yield not far behind.

This is an indication of just how much more expensive capital is today, in a financial environment marked by rising interest rates.

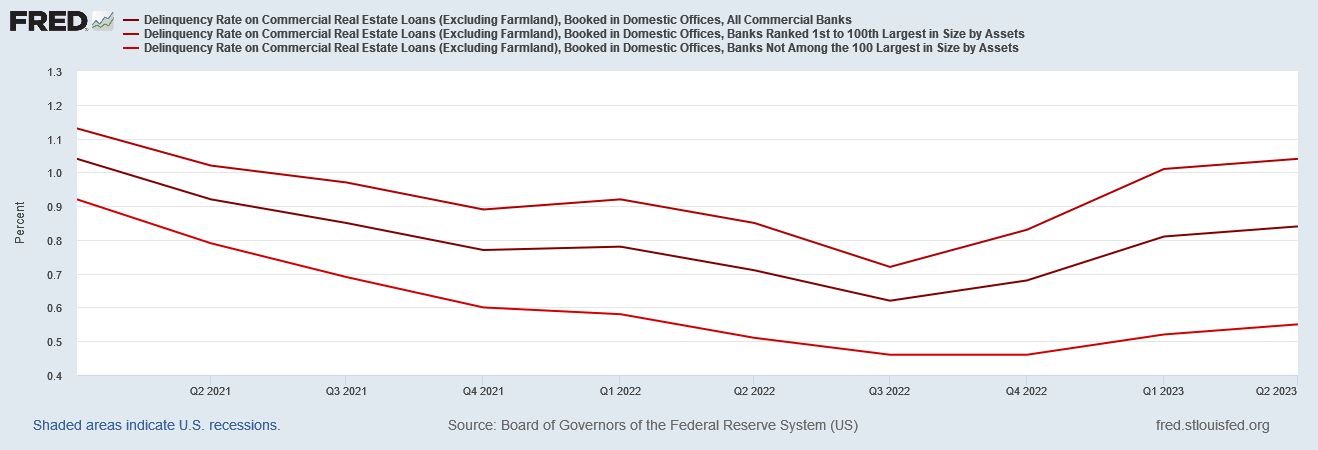

Nor do we need to look very far to see the consequences of the rising cost of capital. Within a quarter of the Fed starting to raise the federal funds rate, the delinquency rate on commercial real estate loans began to rise.

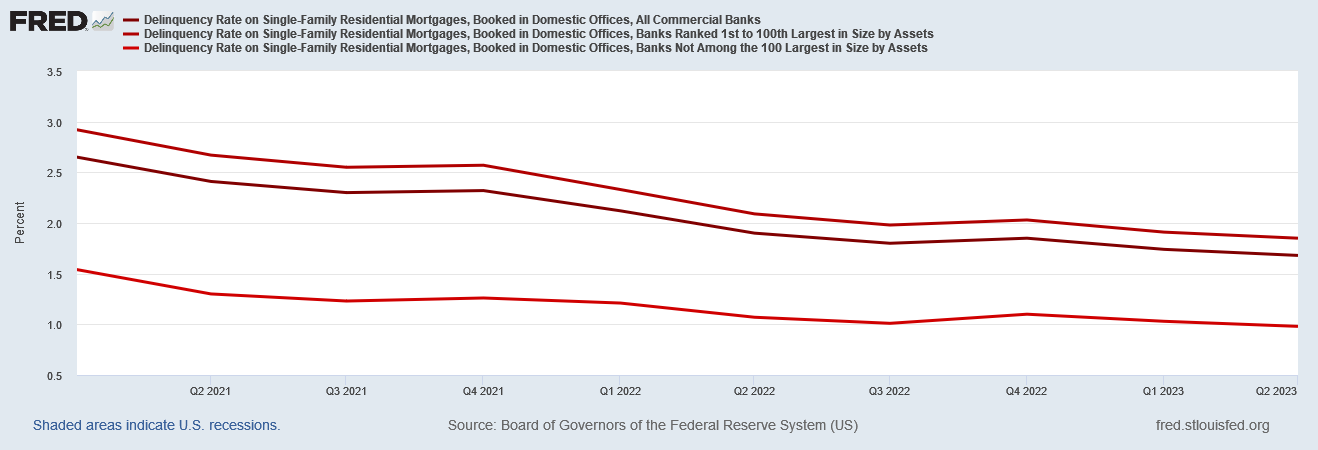

Remarkably, a similar rise in delinquencies is not happening in single-family residential mortgages.

Among commercial and industrial loans not tied to real estate, smaller institutions saw an early rise in loan delinquencies, while larger institutions still have a long-term trend of declining delinquencies.

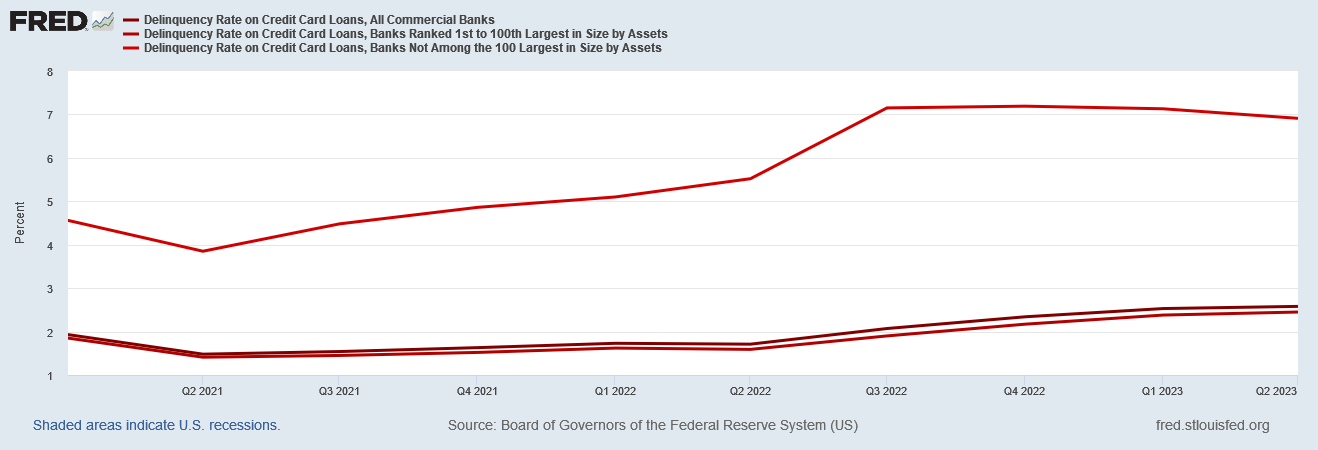

Perhaps unsurprisingly, consumer loans show higher delinquency rates, and were quicker to do so as interest rates began moving upward.

Credit card delinquency rates began moving up as early as the second quarter of 2021—a full year before the Fed began pushing the federal funds rate up.

Delinquencies for other types of consumer loans also began moving up in early 2021.

With the greater delinquency rates among consumer loans, why are commercial real estate loans seen as the greater cause for alarm? The answer is that commercial real estate loans are by far the greater portion of outstanding bank loans.

Commercial real estate is, for many banks, the core of their lending business. When those loans start to go bad, it has a much greater impact on a bank’s financial stability.

When the Federal Reserve began raising the federal funds rate commercial real estate loans began to go bad. Moreover, they are likely to continue to go bad for some time to come. If we look at the market valuations for Real Estate Income Trusts—investment vehicles focused on income-producing real estate1—we see that Wall Street put the highest value on that sector in late 2021 and early 2022, and that REIT values have been declining since then, shedding more than 20%.

As the yield charts above show, the time frame REIT valuations peaked is also the time debt yields began to move up. As yields have moved up, REIT valuations have moved down. With no indications interest rates are about to come down, similarly there is no indication REIT valuations are about to recover.

This is the crisis in commercial real estate that is giving Kevin O’Leary heartburn.

It requires no great understanding of finance to realize that when a bank’s core lending business spirals down into crisis and collapse, that bank is likewise at risk of crisis and collapse. A collapse in commercial real estate would, all on its own, be extremely bad for banks. However, the same forces helping to power the crisis in commercial real estate are themselves threatening to destabilize the US financial sector.

The problem begins with the reality that the relative rise in yields is also the relative decline in the value of existing Treasury and corporate bond. Securities portfolios heavy on older, lower yielding debt instruments are going to be worth less than newer.

How much less? We can gauge how much value various government bond portfolios might have lost by examining the valuation changes in Exchange Traded Funds specializing in government and high-yield bonds. Since the Federal Reserve first began raising the federal funds rate on March 17, 2022, government and high-yield bond portfolios have lost an average of ~12-13%.

Short-term maturities have maintained their value the best, losing only 3% since March of 2022. Longer term maturities have fared the worst, with 10-Year and 20-Year yield portfolios losing nearly 30%.

For banks, this is a problem. Banks both large and small have put considerable capital in treasuries over the past few years, and even though they have been trimming back the size of those portfolios since January of last year, bank securities portfolios are still 30% larger in constant-dollar terms than at the end of Pandemic Panic Recession.

However, the market value of the bonds held within those portfolios has declined an average of 22.21% over the same time frame, going by declines in bond-related ETFs.

Thus there is no question that the same declines in securities values which powered the mini-banking crisis earlier this year are ongoing and perhaps even accelerating.

At the same time, rising market yields are showing signs of reawakening the deposit flight that was the other signature characteristic of that banking crisis.

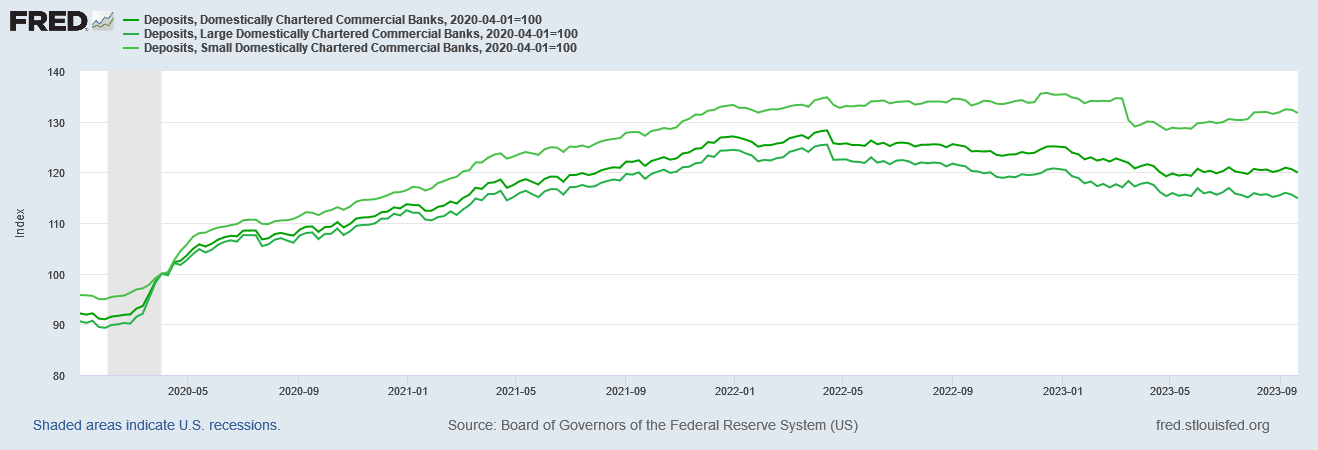

Roughly a month after the Fed began raising the federal funds rate, deposit growth among the nation’s banks peaked and began to head down.

Ironically, the deposit flight has happened most significantly at the country’s largest financial institutions, as is made plain when we index deposit levels to the end of the Pandemic Panic Recession.

This deposit flight was a major catalyst behind the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and later First Republic Bank. In a very real sense, these banks simply ran out of money.

However, for most of the summer it appeared that the deposit flight had stabilized, which helped take pressure (and attention) off banks.

Indeed, since April, deposits at smaller banks have been actually increasing, and at larger banks the trend has been mostly horizontal.

However, at the beginning of September, these stabilizing trends appear to have stopped, and deposit flight is beginning to resume at the nation’s banks.

Thus we are seeing a trifecta of negative forces coalesce in the banking sector beginning to emerge. Loan delinquencies are rising, the value of bank assets is declining, and now deposits are declining once more.

Any one of these trends by itself is a problem for the banking sector. All three trends happening concurrently can only result in a resurgent banking crisis.

This, incidentally is what “contagion” looks like. This is how financial crisis moves from one sector to another.

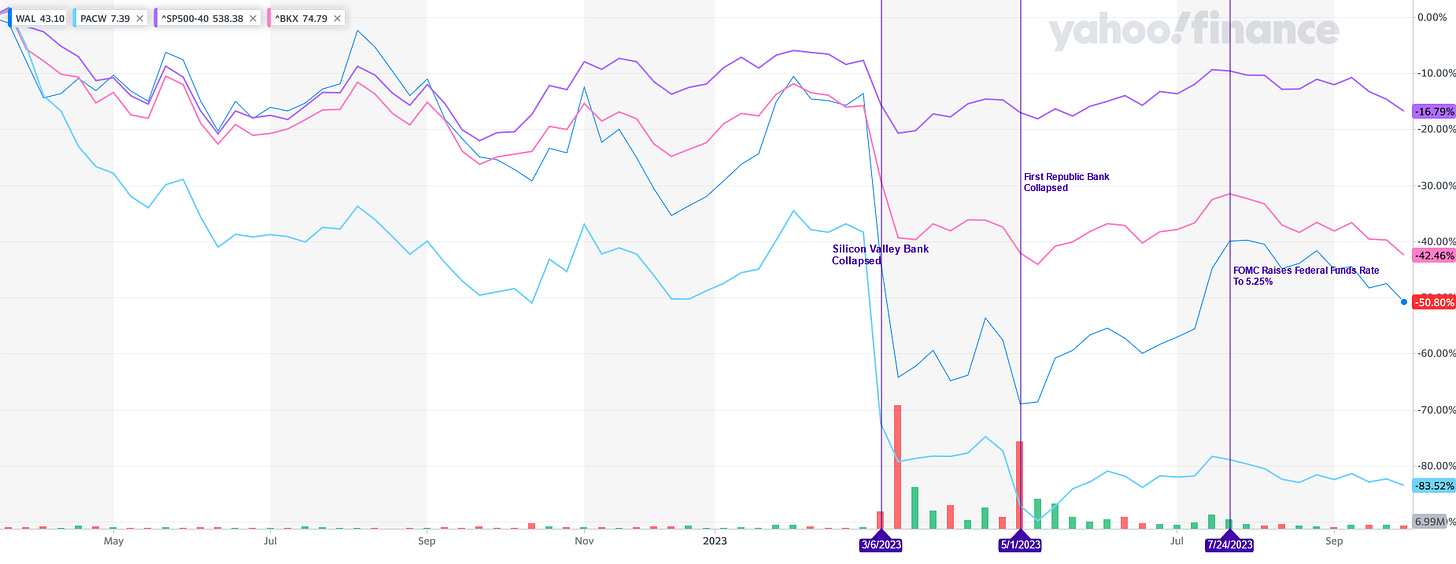

Wall Street very likely knows that a banking crisis is on the horizon. While bank stocks took a beating earlier this year, First Republic’s collapse had broadly signaled stabilization and even price recovery in the banking sector.

However, that recovery trend peaked in July. When the Fed hiked the federal funds rate in July, that largely served as a fresh catalyst to a broader retreat among bank stocks.

Not only has the S&P 500 Financials index been trending down, the KBW NASDAQ Bank index been in retreat since July. Even specific bank stocks such as PacWest and Western Alliance have resumed their downward path. PacWest and Western Alliance were long considered two of the most likely “next” dominoes to fall in a resurgent banking crisis.

There is, of course, no way to predict exactly when either PacWest or Western Alliance will go under. They may not be the next banks to enter into crisis. There are thousands of banks in the US, and all of them are subject to the stresses and crises being described here.

Yet because all banks are subject to the stresses and crises being described here, it is merely a matter of time before one bank succumbs to those stresses. It is only a matter of time before one bank collapses under these serial crises. It is only a matter of a little more time before another bank follows it, and then another.

It is only a matter of time before a banking crisis erupts anew in this country. So long as these trends continue, the ultimate outcome of renewed banking crisis is not in doubt. We are at the stage of pondering not “if” but “when” the crisis will hit.

Contagion is coming.

Chen, J. Investopedia | Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT): How They Work and How to Invest. 24 May 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/reit.asp.

Yep, and the trickle on effect is likely to be felt globally.🤦♀️🤦♀️🤦♀️

No crisis. CRE loans are carried on an accrual basis with loss reserves whereas CDO are marked to market which is why the CDO crisis whacked the entire system--they went from 100 cents to zero in one day. The real crisis is t-bonds which are marked to market and have cratered in price. This will show in the 3Q23 numbers.