A common narrative in the financial media over the past couple of weeks is that the mini-bank crisis which followed Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse in March was brief and has ended. Many pundits position SVB’s collapse as a cautionary tale from which finance—as well as the overall economy—would do well to take away many sobering lessons.

Reports over the past week from more than 15 regional lenders offered plenty of those signs, as multiple executives said the deposit outflows they saw in March had since stabilized or even reversed.

Horizon Investments head of portfolio strategy Zach Hill called the earnings results this past week "better than feared."

The banking crisis "does feel like it's largely contained," added Quant Insight head of analytics Huw Roberts.

Is it contained? Perhaps….or perhaps not. There are considerable indications that March was merely a mild tremor in advance of the main financial earthquake yet to come.

Indeed, there are few who do not at least view the March crisis as the sign of a banking environment that is shifting, and forcing bankers to shift as well.

"Some of the immediate problems have gone away but the reality is with interest rates higher the banks’ business model is going to have to change, and that’s going to play out over months and quarters and even years," Commonwealth Financial Network CIO Brad McMillan told Yahoo Finance.

Moreover, as Credit Suisse demonstrated, the March banking crisis had a truly global dimension, and so must have global ramifications.

Asia is not immune to this coming crisis. Even if the shockwaves emanating from the likes of Silicon Valley Bank in the United States or Credit Suisse in Switzerland are weakening, the fact that Asian economies are more bank-dependent and less capital market-reliant than those elsewhere will tell.

Asia’s corporate sector, and especially that of “emerging” Asia, is highly exposed in terms of borrowing relative to gross domestic product size, according to the Institute of International Finance data at the end of 2022. The ratio for corporate Asia was 130 per cent, well above the 97 per cent figure in mature economies.

Some of the consequences are easy to see and easy to comprehend—such as the diminution of borrowing.

And yet, just below the surface, signs are mounting that credit is drying up in pockets of the economy at a worrisome rate.

Small businesses say it hasn’t been this difficult to borrow in a decade; the amount of corporate debt trading at distressed levels has surged about 300% over the past year, effectively locking a growing swath of businesses out of financial markets; bond and loan defaults have ticked up; and the Federal Reserve says banks have tightened lending standards. Corporate bankruptcies are on the rise, too, particularly in the construction and retail industries.

The creditworthiness of some banks is also an easily foreseeable outcome from the March crisis, hence Moody’s recent downgrade of 11 banks.

The rating agency said strains in the way banks are managing their assets and liabilities are becoming “increasingly evident,” and are pressuring profitability. Recent events “have called into question whether some banks’ assumed high stability of deposits, and their operational nature, should be reevaluated,” the ratings firm said in its report.

Still, with thousands of banks in the US alone, surely the fact that 11 are showing signs of financial distress is not, by itself, cause for much alarm. How does 11 banks being downgraded by Moody’s portend larger problems for the banking industry as a whole?

One reason the events of March take on a larger significance is that the driving forces behind both the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and the near-collapse of First Republic Bank are common across the banking sector, especially the challenge of declining bank deposits.

If we index to January, 2022, the total deposits at large domestically chartered banks, small domestically chartered banks, all domestically charted banks, and foreign institutions, we quickly see that declining deposits are a phenomenon everywhere but at foreign institutions.

Moreover, as I outlined last fall, the Fed’s campaign to push up interest rates in an effort to bring down consumer price inflation paradoxically has always been bound to cause a money shortage at some juncture. That instability is not merely unavoidable, it’s a structural part of what happens as interest rates rise.

11 banks with cracks in their financial foundations are a warning sign that we should look to the financial foundations of the US banking industry as a whole—and when we do, what we see is far from comforting. The inevitable signs of impending breakage are mounting.

The first and most glaring point of weakness has been the decline in bank deposits over the past year.

Large banks in particular have shed billions of dollars in deposits. If we index the level of bank deposits for all commercial banks, large and small domestically chartered banks1, and foreign banks, we see that the magnitude of the declines overall track almost precisely the magnitude of declines among large domestic banks. That magnitude is far greater than the magnitude of decline for small domestic banks.

In both absolute and relative terms, large commercial banks have lost more deposits than small banks.

Most disturbing of all, however, is that this is the first time in over 40 years worth of banking data that deposits have posted extended declines.

This is not a comforting first to see in banking.

Nor is it the only decline the banking industry has seen. Bank credit growth is has declined dramatically, year on year, and is at its lowest level in ten years.

In absolute terms, bank credit in the US peaked last December, and has since been declining, the first extended decline in since the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis.

One curious aspect of these twin declines: While bank credit has generally outpaced deposits, after the 2020 government-ordered recession, deposits surged above bank credit and remained significantly above bank credit until just the past year.

While bank deposits, as of the last measurement, still outpace bank credit, the beginning of March was the first time—however briefly—since the 2020 recession these two metrics inverted. Bank credit edged briefly above deposits right at the beginning of March, when banks were on the verge of a significant meltdown.

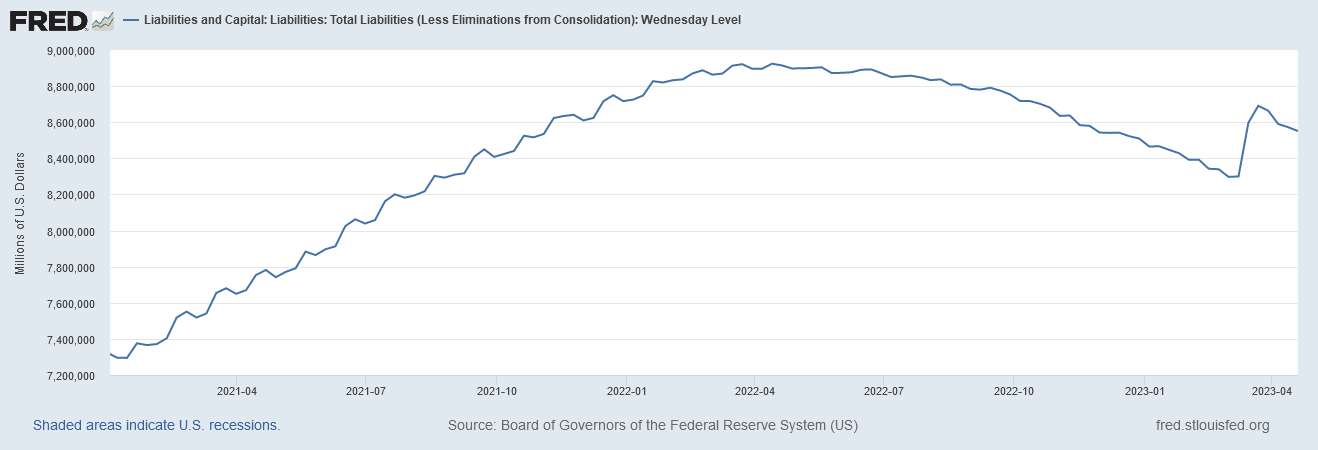

The broad impact of the Fed’s actions thus has been to begin shrinking the money supply, effectively pulling dollars from the system. Among other things, this means that liquidity within the financial system has also begun to shrink.

The brief inversion between deposits and credit issuance also is an indication the banking industry’s concerns and weaknesses are far more systemic than the failure of a few individual banks, or the credit downgrades of 11 other banks, might suggest. Deposit loss is a challenge for the banking industry as a whole, not just a few isolated banks. Declining credit issuance is a challenge for the banking industry as a whole, not just a few isolated banks. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, as well as the bank run at First Republic Bank, was possible in March at essentially any US bank, and in particular any of the large banks.

The ongoing declines of deposits and credit issuance tells us that these things very much can happen again at any time. The March bank crisis can (and very likely will) return—something I have discussed previously.

As much as the specific collapse of Silicon Valley Bank can be traced to the specific decisions of the bank’s leadership, what we see in the industry-wide data is that not only are bank leaders overall making bad choices, but that the Federal Reserve infrastructure has set the stage for those bad choices having extraordinarily bad consequences.

To understand what systemic issues might be at play here, it helps to take a step back and get a broad overview of the major changes in the financial system from 2020 onward—which fortunately can be summarized in a single only slightly confusing chart.

Let’s unpack this chart a bit.

The 2020 lockdown produced, naturally, the 2020 recession, to which the Federal Reserve responded by driving down interest rates to near zero (the federal funds rate effectively was zero percent) and hugely expanding the M1 money supply, as the left side of the chart shows. Intriguingly—and somewhat counterintuitively—significant consumer price inflation did not emerge from this expansion until more than a year afterwards, as it was not until March of 2021 that inflation exceeded 2% (after which it quickly rose, reaching 4% in April, 20210.

At the same time, even though the Fed had pushed interest rates to zero, yields on 10-Year Treasuries rose, from between 0.6%-0.75% during the summer of 2020 to 1.09% in February of 2021, 1.45% in March of 2021, passing 1.75% by April, 2021.

Consumer price inflation stabilized briefly during the summer of 2021 at around 5.4%, holding there between June and September. By October, however, inflation climbed to 6.2%. While the yield on the 10-Year Treasury had slipped back to 1.4% during this period, in October the yield on the 2-Year Treasury began to rise, ticking up to 0.27% and reaching 0.76% by the end of December.

By February of 2022, consumer price inflation reached 7.87%, and by the end of that month, the 2-Year Treasury yield had risen to 1.44%, while the 10-Year Treasury yield stood at 1.83%. Yields had risen by a full percentage point without any inducement from the Federal Reserve via the federal funds rate, which would not be raised until the middle of March. During that same month inflation reached 8.5%.

Between March and May inflation again held more or less steady around 8.5%. However, at the end of April, both the M1 and M2 money supply metrics began to decline for the first time. Both metrics have been incrementally trending down ever since. May also saw the first sign of resistance to the Federal Reserve rate hikes, as the 2-Year Treasury yield slipped when the federal funds rate was pushed up to 1%. Subsequent to the federal funds rate hike the treasury yields retreated slightly.

Inflation peaked in June of 2022, at over 9%, while the federal funds rate was pushed to 1.75%. Treasury yields also surged in the middle of June—to 3.43% for the 10-Year yield, and 3.4% for the 2-Year yield.

By November, inflation had retreated to 7.1%, while the federal funds rate had been pushed to 4%. Treasury yields peaked in November—4.22% for the 10-Year Treasury and 4.72% for the 2-Year Treasury. Yields would move mostly sideways and decline marginally until February of this year, when the yields began picking up again, with the 2-Year Treasury topping 5% and the 10-Year Treasury topping 4% by early March.

In March, of course, was the mini-bank crisis. Treasury yields dropped by more than a percentage point during the crisis, even as the federal funds rate remained constant. Only in the past week have yields begun to move up again.

It is against this backdrop of rising inflation, rising interest rates, and a shrinking money supply that we must view trends such as declining liquidity. In this context, where unrealized losses on securities portfolios are mathematically certain, the reduction in liquidity guarantees that banks will eventually run out of dollars. The banks’ failure to unwind their securities portfolios before now carries the much magnified cost of bank runs and insolvencies.

The money supply reduction sheds light on how the financial landscape has shifted for banks. In the aftermath of the 2020 recession, Fed decisions to slash the federal funds rate to zero, while using quantitative easing mechanisms to greatly expand the money supply, the best returns for banks were frequently found by building portfolios of treasuries and other securities, even at the low yields then in play. Those low yields began to end during the summer and fall of 2021, and were terminated completely by the Fed’s federal funds rate hikes beginning in March of 2022.

Thus the Fed sabotaged the value of banks’ investment portfolios even as they were removing vital dollars and liquidity from the system.

Recalling the liquidity chart above, we can see clearly the inevitable outcome.

The sudden reversal and rise in liquidity in March was the result of the Fed’s emergency loan programs to “stabilize” the banking industry after the Silicon Valley Bank collapse. Deposit flight coupled with the Fed draining liquidity from the system had left SVB without adequate dollars to satisfy depositor demands for their deposits.

Even more importantly, consider how the treasury yields behaved during this period.

Notice how yields dropped the same week the Fed provided a burst of liquidity. This is a clear signal of a tipping point being reached. Regardless of where the Fed wants interest rates, the market forcefully rejected yields above 5% for the 1-Year and 2-Year yields, and above 4% for the 10-Year yield. Whether that makes the 4%-5% interest rate the “natural” interest rate or merely the highest rate the markets can tolerate for now is still a question.

Additionally, declining deposits are placing funding stress on banks, while rising interest rates are impairing the value of their financial assets—both loans and securities portfolios. Coupled with liquidity decline, the amount of stress banks have come under is enough to begin causing banks to fail.

Yet the burst of liquidity last month has been only temporary, and the Fed has already pulled more than half of that back—even as Treasury Yields have begun rising once again. If March represented a tipping point, the financial system is already moving perilously close to that same tipping point once again.

Adding to the financial stress are the mounting unrealized losses on banks’ securities portfolios. As yields rise, banks’ legacy investments in low-yield securities lose market value, reducing the capacity of those investments to be sold to cover deposit demands as people continue to pull their cash out of the banking system. When we look at the market value of various Exchange Traded Funds dealing in debt securities, we can immediately see the valuations are heading south again. Unless market sentiment has shifted, things are approaching the same meltdown threshold that was reached in early March. That means a fresh banking crisis is potentially just days away.

In May, the Federal Open Market Committee meets, and will set the new federal funds rate for the next few months. Jay Powell will have to decide whether to push rates up or leave them be. Yet the real question facing the Federal Reserve Chairman will be how much more can he push the system before something else breaks?

The data suggests the answer is some variant of “not too much more.”

The Federal Reserve defines “large domestically chartered banks” as “…the top 25 domestically chartered commercial banks, ranked by domestic assets as of the previous commercial bank Call Report to which the H.8 release data have been benchmarked.” All other domestically chartered banks are by definition considered “small domestically chartered banks”.

Wow - there’s some really ominous data here. So a bank liquidity crisis is shaping up, probably so massive that the federal government will have to again step in and reimburse lost deposits by the trillions. Looking at the long game of chess moves here, do you see hyperinflation developing, followed by collapse into a Great Depression and serious deflation? Or is there a more optimistic outcome likely?