Is Another Banking Crisis About To Unfold?

Does It Even Matter If The Fed Raises Rates In Two Weeks?

In the Federal Reserve’s efforts to contain and bring down consumer price inflation, there has been one piece of good news that has gone largely unnoticed the past couple of months: compared to headline inflation per the Consumer Price Index, real Treasury yields have been positive for the past two months, for the first time in years.

This is a significant milestone, because it signifies that interest rates being to reflect a true cost of capital, and that monetary policy is legitimately tighter and less liquid than it has been before.

While real yields are not yet fully positive with respect to core inflation, they are at least within 100bps of the zero bound—again, for the first time in years.

However, this progress on yields carries its own price tag: the banking system may be heading into another episode of instability and lack of liquidity.

With the Federal Open Market Committee set to meet on the 20th to decide whether another federal funds rate hike is in order, the stage is being set for the Fed to decide whether or not to roll the dice on a new banking and liquidity crisis—and even if the Fed decides to stand pat on the federal funds rate, a liquidity crunch may still happen.

When the FOMC decided in June not to raise the federal funds rate, it appeared at that point as if the Fed would be able to successfully kick the interest rate can down the road and avert a continuing banking and liquidity crisis.

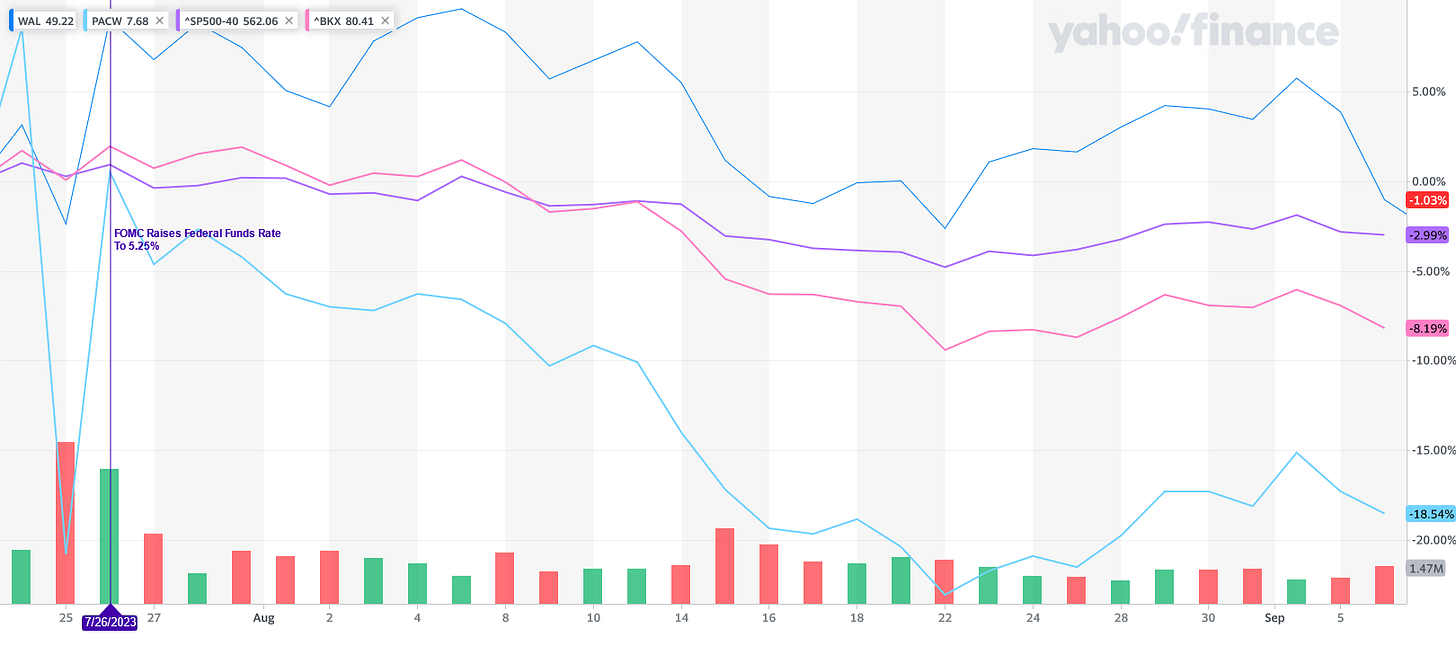

However, with the FOMC having opted to raise the federal funds rate to 525 bps in July, signs of potential banking issues have begun to re-emerge.

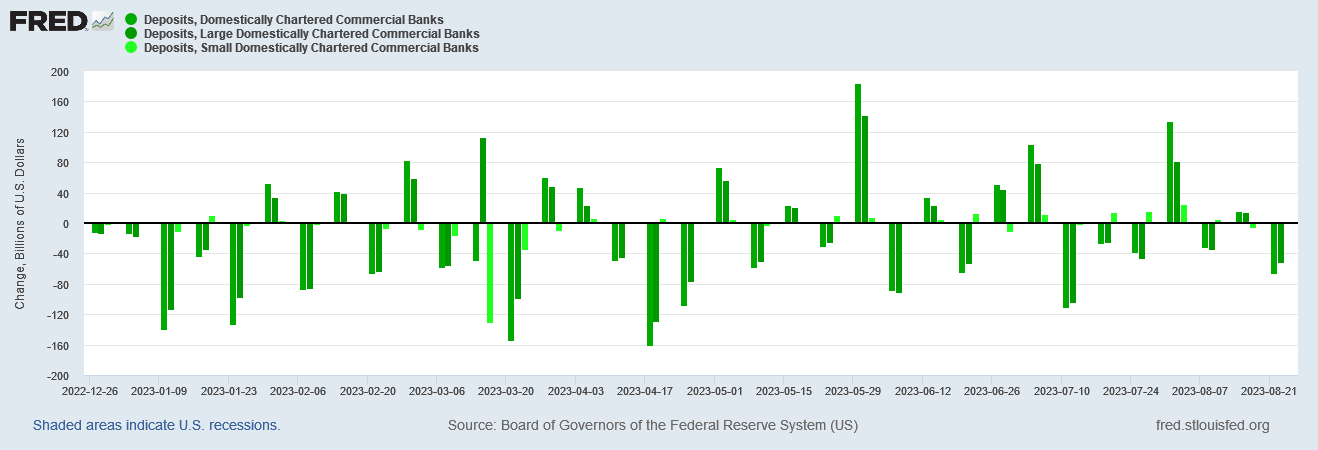

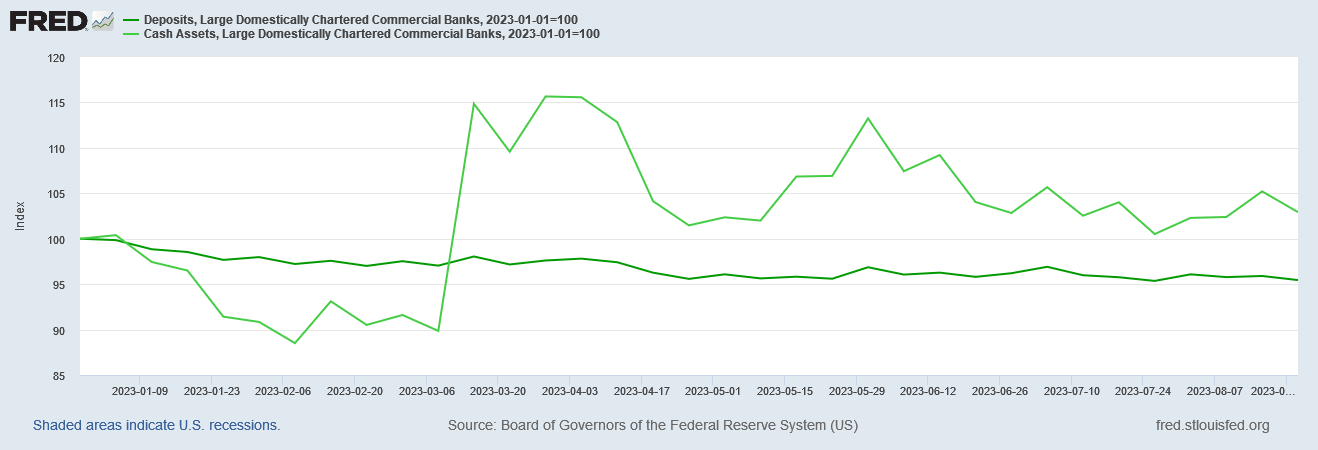

First and foremost, there are signs the banking system is hemorrhaging deposits once again.

Not only is the deposit level for America’s large banks at its lowest level for the year, but we are seeing another divergence between the small bank deposits and large bank deposits. While the divergence is not absolute proof that financial instability is on the way, there is an indication that deposit outflows are predominantly taking place among larger institutions, just as was the case earlier in the spring.

That deposit outflows have resumed is an indication that there is still a fundamental imbalance within the banking system. For at least a time starting in early May, that imbalance appeared to have eased, allowing deposit levels at both large and small banks to stabilize, albeit at a lower level than at the beginning of the year.

However, just before the FOMC raised the federal funds rate at the July meeting, deposit outflows resumed at large domestically chartered banks. Curiously, small banks have still seen their deposit levels increase, thereby contributing to the imbalance between large and small institutions.

Additionally, there is greater deposit volatility at large banks than at small banks. We see this developing when we look at the current year’s changes in deposit levels week by week.

Large institutions are seeing large fluctuations where deposits are reduced one week, increased the next only to be reduced yet again the week following that. Since the first week in July most notably, large banks (and, as a consequence, domestically chartered banks as a whole) have seen mainly deposit reductions.

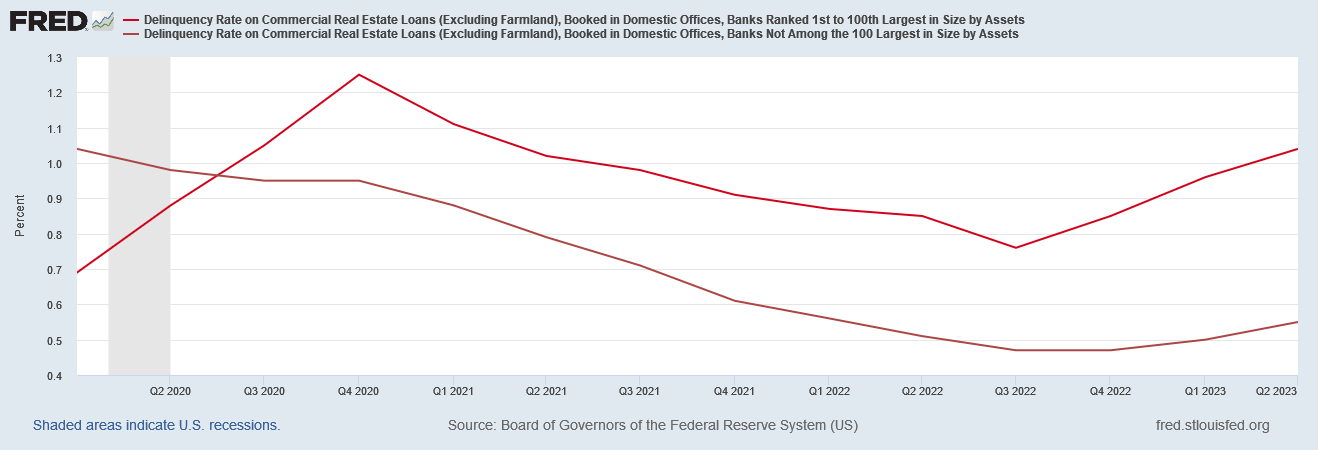

While deposits are decreasing particularly at large banks, delinquencies on commercial real estate loans are increasing, particularly at large banks.

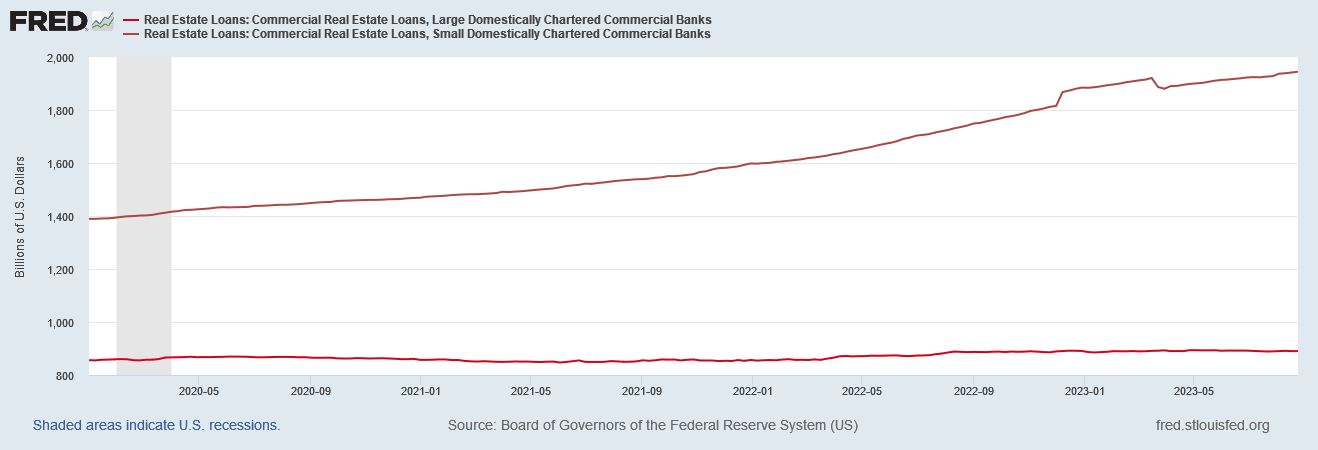

While the correlation within the bank data is not precise, the delinquencies at the nation’s 100 largest banks are noteworthy, because commercial real estate loans themselves are being made primarily at smaller banks.

Within the Fed data set, “small domestically chartered commercial banks” are those banks not within the 25 largest domestically chartered commercial banks, which means there are some notionally “small” banks who within the delinquency data fall within the 100 largest banks. However one breaks out the data, however, the reality remains that delinquencies are concentrated within a discrete segment of the banking sector, with at least some of those banks also experiencing significant deposit flight.

This is the same imbalance that was beginning to emerge earlier this year during the banking and liquidity crisis.

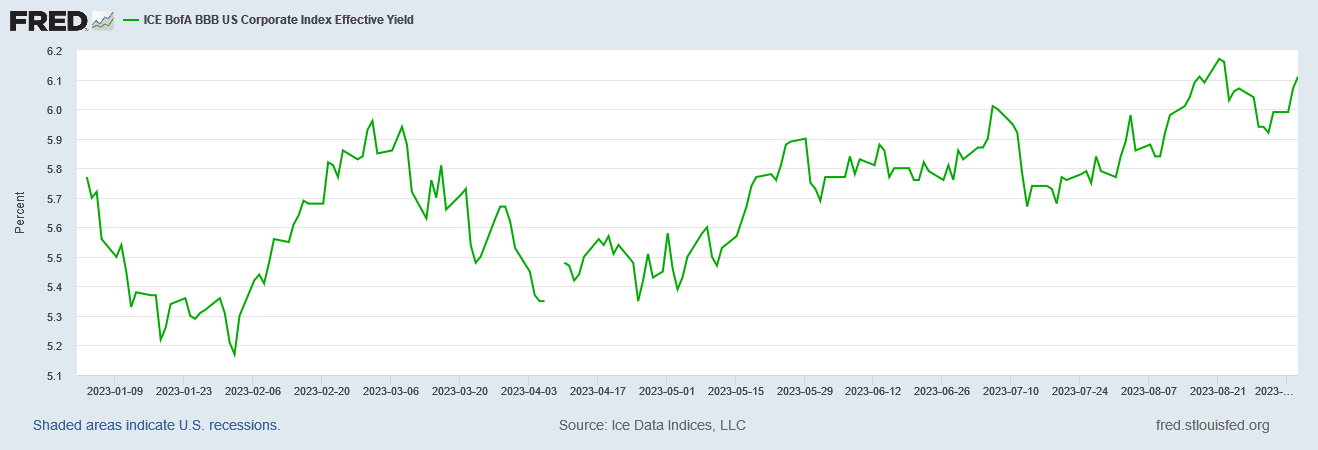

Many of the forces driving this imbalance, such as rising corporate debt yields, have continued to advance.

Now, as before, rising debt yields present a quandary commercial real estate debtors: pay higher interest rates to roll over maturing debt or attempt to pay the debt down.

Now, as before, Exchange Traded Funds focused on mortgage-backed securities are steadily losing value, as higher interest rates on new debt issuance degrades the market value of previous.

Even ETFS which trade on Treasuries are showing significant price erosion of late, indicating that holdings of current government securities have lost significant market value.

Rounding out the indicators of impending crisis are the recent decline in market valuation for bank stocks in general, and for PacWest and Western Alliance, two of the banks previously identified as probable candidates for banking dominoes likely to fall in an extended crisis.

There are also indications that the banks themselves—again, particularly the large banks—are aware that rough waters might lie ahead, and are taking predictably defensive measures.

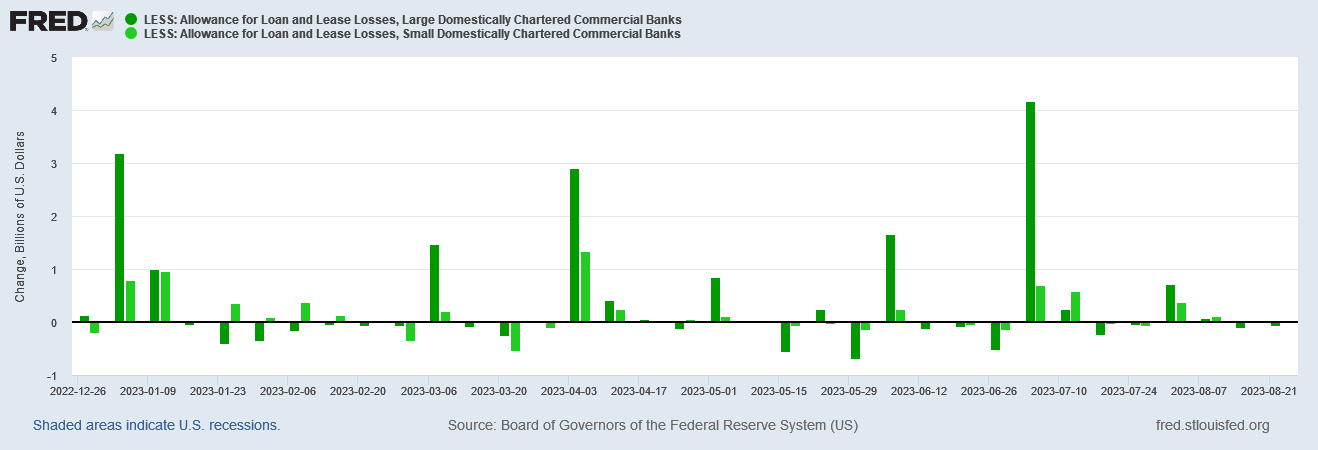

Both large and small banks have been steadily increasing their provisions loan losses throughout 2023, with large banks making a particularly large such allowance in early July.

On a percentage basis, large banks have increased their loan loss reserves by 11.8% since the first of the year, while the small banks have made a 9.3% increase in loan loss reserves.

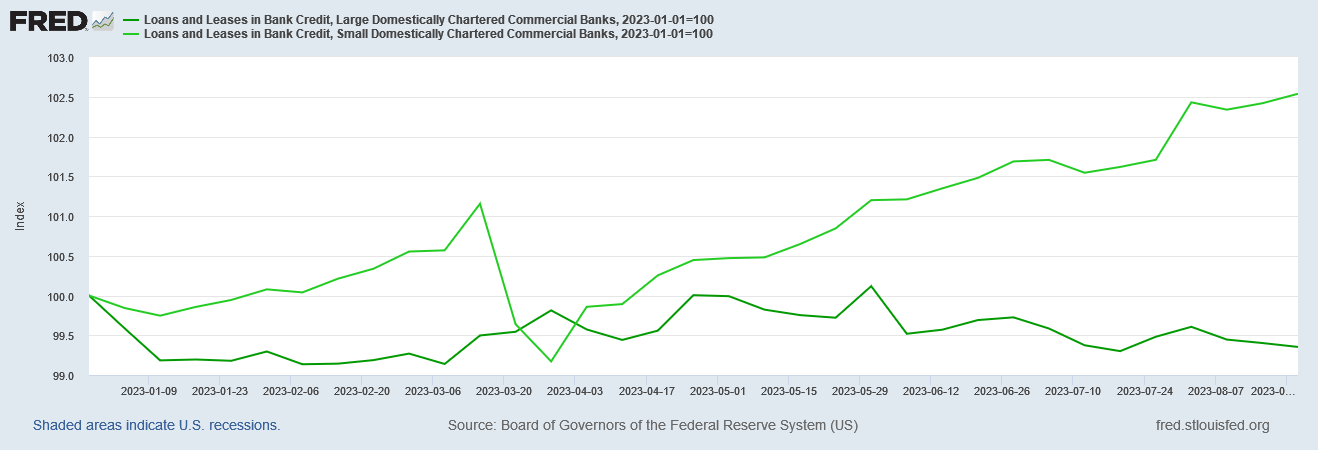

At the same time, large bank loan books are shrinking, while they are increasing at small banks—the total amount of loans at small banks has risen 2.5% since the first of the year, but has dropped 0.6% at large banks.

The defensiveness percolates down to commercial real estate loans as well: small banks have increased the size of their CRE loans by 3.2% since the start of the year, while large banks have trimmed their CRE portfolios by 0.1%.

Nor is the defensiveness limited to loans and loan losses. Even as banks have seen deposits decrease, they are increasing their cash assets. Against a smaller deposit base they are adopting a more liquid posture.

Large banks have increased their cash assets by roughly 2.9%, as their deposits have decreased 4.6%

Small banks have managed to achieve a far more liquid posture: their cash assets are up 12.1%, while their deposits are down 2.9%.

Large banks are making more defensive moves than small banks, even as small banks are succeeding in boosting their own liquidity more than large banks. In a bit of perverse irony, large banks are showing less confidence in their own balance sheets than small banks, yet are having less relative success improving their cash positions.

In some regards, this should not be a surprise. As I noted earlier in the summer, while the big banks posted good second quarter results, there were a number of warning signs present in their balance sheets.

While these data points do not mean that one of the thousands of banks in the US is about to go under next week, they do mean that market conditions are returning to those which prevailed when Silicon Valley Bank and later First Republic Bank stumbled and then collapsed. Even without the Fed raising the federal funds rate at the next FOMC meeting on the 20th, we are seeing the necessary elements of a banking and then liquidity crisis. The stage is being set, and all that is needed now is for a bank or two to face an escalated depositors’ run. SVB and the other major bank failure alongside SVB, Silvergate, are blunt object lessons on how quickly a bank run can emerge.

As we can see from the data on loan loss provisions, the banks perceive at least some risk. Their loan books are deteriorating, and the market value of their securities portfolios is slipping away. Default rates in commercial real estate are rising. It does not require a PhD in Finance to see that trouble lies just ahead.

Moreover, many of these warning signals emerged even before the last FOMC meeting, and thus before the last increase in the federal funds rate. The Fed raising the federal funds rate in July may have amplified the defensive and downward trends, but these trends very much predate the July rate hike.

Even if the Fed opts to stand pat on interest rates now—as Wall Street fully expects them to do—that obviously cannot be enough to halt deposit outflows. The deposit outflows are already happening, and leaving rates where they are changes nothing. Standing pat on rates will not make rolling over existing CRE debt any cheaper. Raising the federal funds rate would very likely accelerate deterioration within the banking system, increasing the deposit outflows and raising debt default rates, but simply standing pat on the federal funds rate is not going to prevent deterioration within the banking system.

The blunt reality is that, at this juncture, if the banking dominoes are lined up to begin falling once more, there is not much the Fed can do to stop it. Only time and not the Federal Reserve will determine if the second phase of the banking crisis is set to begin.

The FERAL Reserve (which is neither federal, nor does it have any real reserves) is really playing with fire now!

"Curiously, small banks have still seen their deposit levels increase, thereby contributing to the imbalance between large and small institutions".

I'd like to know by what percent, they have increased and whether it correlates with the loss from the big banks or is slightly less?🤔🤔🤔😉

Frankly I'm hoping it's an indication that people are becoming more aware of the looming Financial crisis (still tracking right on schedule btw😉), and the BIS, IMF and WEF plans, and are taking steps as individuals to support local institutions, keep cash alive and reject the larger banks, as per financial recommendations by Catherine A Fitts, and others.😉

I'd like to think so but I'm not holding my breathe.😐