Wall Street does love its signals and indicators, and every one of them is fraught with significance and meaning. Just ask a Wall Street analyst—they make a living filling corporate media with bloviations about how this yield or that index is flashing recession or showing growth momentum or something.

Over the past week, the indicator du jour has been the 10-Year Treasury Yield, which suddenly is of great concern to the markets, fearful that Jay Powell may finally have found the right combination of asset sales, press conferences, and faux rate hikes via the federal funds rate to push market yields up to where he wanted them to go last year.

The 10-year Treasury yield — a key baseline for the cost of money across the financial system — has jumped more than four full percentage points over the past three years, briefly pushing it this week over 5% for the first time since 2007. It’s the biggest increase since the run up in the early 1980s, when Paul Volcker’s efforts to slay inflation pushed the 10-year yield to nearly 16%.

Of course, other analysts have concluded that the rise in the 10-Year Treasury Yield means the Fed will punt yet again on the federal funds rate at the next FOMC meeting.

The yield on the 10-year Treasury has been steadily climbing in recent weeks and has hit several multiyear highs this month. Investors have been considering the outlook for interest rates ahead of the Federal Reserve’s next policy meeting on Oct. 31 and Nov. 1.

Several Fed officials have suggested that higher Treasury yields will create tighter financial conditions, which could slow the economy. That could mean the Fed does not need to hike rates, and it prompted many investors to believe rates will be left unchanged next week.

Still, the prevailing views remain that high interest rates are bad and will send the economy spiralling, and that the Fed is committed to keeping rates high because inflation is high.

The irony of these views coming in these the waning days of 2023 is that they are the same concerns that were floating around in the waning days of 2022. A full year has come and gone, and Wall Street is pouring the same flavor of Kool-Aid.

Long-time readers may recall that it was this time last year that I described how Wall Street was determined to watch the coming market crash and not do a damn thing about it.

The persistent insistence on Wall Street that things will break if the Fed continues to push rates up tells us one more very dangerous and very tragic thing: Wall Street won’t take the hint and act now to get ahead of the crisis.

Wall Street needs to unwind its derivative investment transactions, and it needs to do so starting yesterday. The urgency is immediate and real. Wall Street’s fear of a breakdown in US Treasury bond markets indicates they already know that this needs to be done.

At the time, there was ample reason to believe that something not very nice was about to unfold, as just the month before investors were all running scared in the same direction.

With sovereign debt yields rising everywhere, equities (stocks) dropping everywhere, and the dollar becoming everyone’s new financial best friend, the investor class appears to all be running in the same direction at the same time. The investor class is expecting something somewhere to go horribly wrong, in a way that has major economic ramifications. I expect events will prove them correct, and fairly soon.

Hence the warning at the top of this article: Be afraid. Be very afraid.

However, a funny thing happened after I wrote those two articles….nothing.

Treasury yields stopped rising.

Equities were mixed for the last part of 2022, with the Dow Jones rising and the NASDAQ falling.

The dollar, which had been gaining ground against other major currencies, declined.

The apocalypse, which at the time seemed just around the corner, decided not to arrive after all.

However, while 2022 ended without the financial meltdown that seemed imminent last October, it was just a couple months later that first Silvergate Capital and then Silicon Valley Bank collapsed within days of each other in early March.

While the two banks served different markets and had different customer bases, the proximate cause of the failure of each was simply running out of money—a.k.a., a “liquidity crisis”.

One signature element of most liquidity crises: rising interest rates, and in 2022 interest rates rose because Jay Powell wanted them raised.

We must remember that Silicon Valley Bank in particular was not the sudden collapse the media pretended it to be, but was in fact a fairly slow-motion implosion that had been developing for over a year.

If one follows the corporate media timeline laid out above, one might easily conclude that Silicon Valley Bank’s problems erupted out of nowhere last week, without warning and without any indication the bank was in any difficulty.

However, the reality is the warnings were there—but no one was paying attention, until it was too late.

Which brings us back to the present day, where Treasury yields are again rising.

Since July, the stock markets have been in retreat.

For its part, the dollar, after moving mostly sideways during the first half of the year, has been climbing steadily.

Are these leading indicators of a new banking and/or liquidity crisis?

As I have discussed at length across a series of articles, there are certainly several warning signs.

There are signs of a coming crisis in commercial real estate with its attendant debts.

There are still signs that banks have not resolved their problem of declining market valuations for their securities portfolios.

There are even warning signs of a coming crisis involving residential real estate and mortgages.

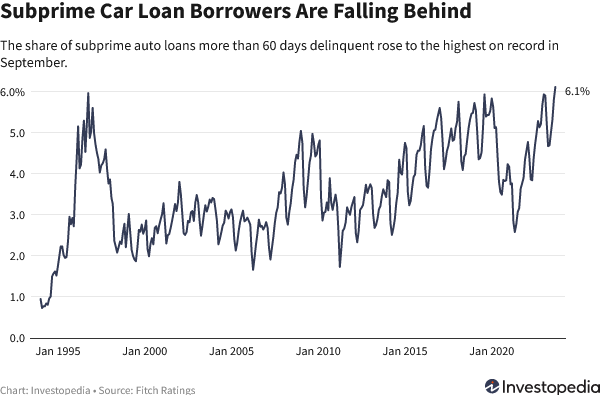

To these, we can also add rising delinquencies in automobile loans.

As of September, 6.1% of U.S. subprime borrowers—those with the lowest credit scores—were 60 days or more behind on their car payments, up from 5.87% in August and the highest share in data from Fitch Ratings that go back to 1994, as the chart below shows.

This is quite a reversal from the immediate aftermath of the Pandemic Panic Recession, when car repossessions and delinquencies had dropped to lows not seen since before 2015.

Car repossessions tumbled in the early days of the pandemic as the government sent trillions in stimulus money to American homes and businesses. But repossessions have progressively ticked higher as sky-high prices for used and new cars alike forced consumers to take out bigger loans.

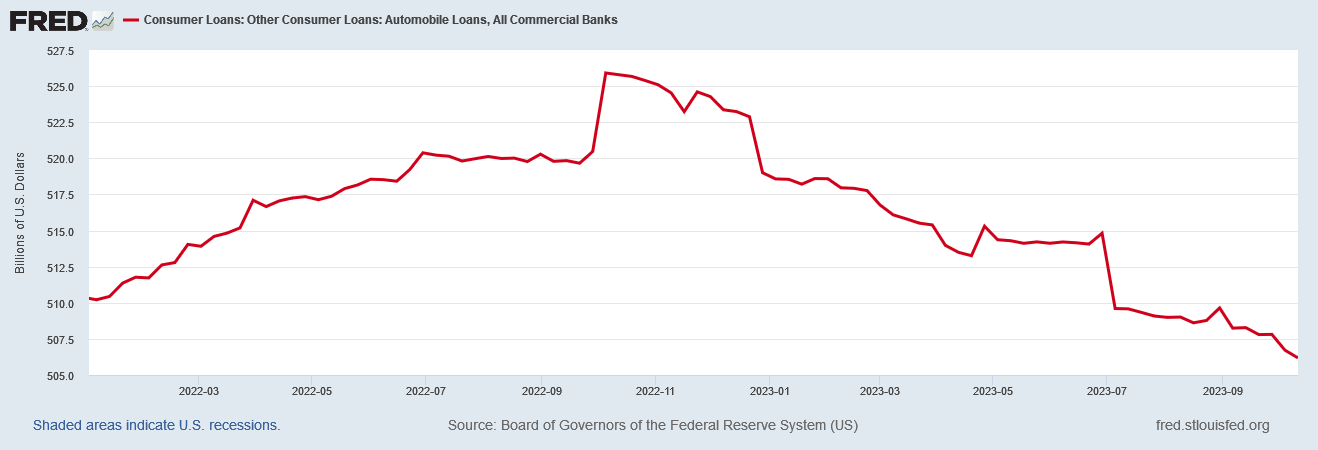

Another warning sign: automobile loans have been declining since October of last year.

If banks aren’t writing automobile loans that suggests automobile loans are falling out of favor with banks. There’s usually a reason why that is, and that reason is not likely to be good.

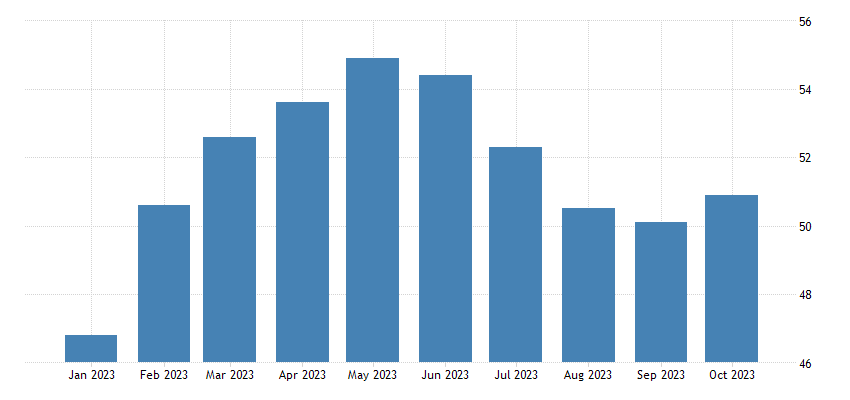

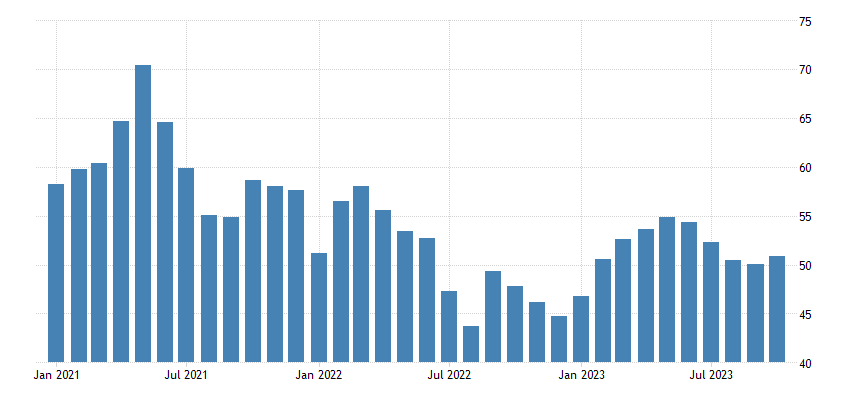

Yet Wall Street is also enjoying a burst of good news on the economic front, with the S&P Global Flash PMI data showing the economy expanding in both the manufacturing and service sectors.

US companies signalled a marginal expansion in business activity during October, following broadly stagnant output seen in August and September. Manufacturers and service providers alike reported improved activity levels as the downturn in demand moderated. The rise in total output was the quickest for three months.

Demand conditions at manufacturers improved for the first time since April, while service providers saw a slower drop in new orders.

More precisely, the Manufacturing PMI inched back up to the 50 threshold between expansion and contraction, its highest reading since April.

The Services PMI moved somewhat farther into expansion territory, rising to 50.9 from 50.1 in September.

Naturally, the Composite PMI followed suit, rising to 51 from 50.2.

Wall Street looks to the PMI data as a leading indicator of economic health.

The U.S. economy improved at the start of the fourth quarter due to slower inflation and fresh hopes that interest rates have peaked, a pair of S&P surveys showed.

The S&P flash U.S. services-sector index rose to a three-month high of 50.9 from 50.1 in the prior month. Most Americans are employed on the service side of the economy.

The S&P U.S. manufacturing-sector index, meanwhile, climbed to a six-month high of 50 from 49.8 in prior month. The index has been in negative territory since last spring.

Thus, even though yields are signalling a coming recession, even though debt instruments of various kinds are becoming increasingly dicey investment propositions for banks, the economy is doing well because the PMI data said so.

Or, despite the PMI data showing economic expansion, rising yields and delinquencies on debt mean rough economic waters ahead.

Both narratives work just as well with the headline data.

As per usual, however, one has to look beyond the headlines to get a true sense of what the data actually indicates.

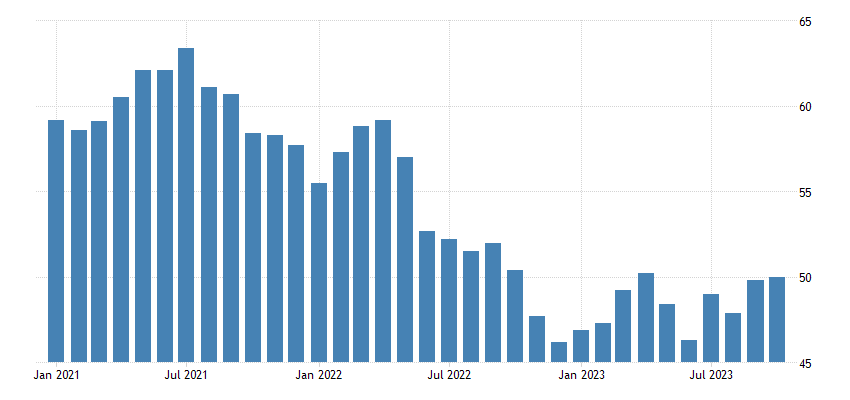

In the case of the PMI data, while the recent trend is somewhat positive, the longer term trend reveals significant weakness within both manufacturing and services.

Manufacturing is printing significantly below where it was this time last year, and even more so compared to 2021.

The services trend since 2021 has also been downward, although early 2023 was better than for manufacturing.

Unsurprisingly, the Composite PMI shows the same, as it is the amalgamation of the Manufacturing and Services PMI data.

None of the PMI trends suggest any sort of long-term recovery, expansion, or growth in either Manufacturing or Services—and yet these stats presumably augur well for the fourth quarter of 2023.

Neither corporate media nor Wall Street appear to be looking at the data beyond the headline numbers. There is no serious assessment taking place of the longer trends even in the PMI data, which shows clear weakness across the US economy.

Nor is Wall Street considering the implications of the mixed and even contradictory signals that were evident in last month’s Producer Price Index data.

The context for the Producer Price Index Summary is that energy prices have been rising for the past few months and that is being reflected in headline inflation, both factory gate inflation and consumer price inflation. We see that throughout the inflation data. We also see that, based on last week’s dramatic reversals in oil prices, energy prices are done rising, which means an abatement of energy price inflation and thus a moderation of inflation overall—which in turn means factory gate inflation is not “heating up”, despite what corporate media and the “experts” want to believe.

With factory gate prices for goods either stagnant or in decline, and with factory gate inflation for services seemingly intractable, what the PPI is showing when all the data is examined is not rising inflation across the board but a continuation of the stagflationary trends we have been seeing for some time.

Wall Street is also not giving much thought to the possibility that consumer prices are likewise heading into a stagflationary slog, where inflation becomes embedded in the economy at higher rates than before the pandemic, resulting in little or no real economic growth.

What is not good news is that, for a number of consumer price elements such as rent of shelter, inflation is receding only very little and for others receding not at all. Consumer price inflation is not increasing by multiple percentage points for the moment at least, but neither is it coming down with anywhere near the speed with which it rose. Some prices are coming down, but others are proving intractable and downright stubborn.

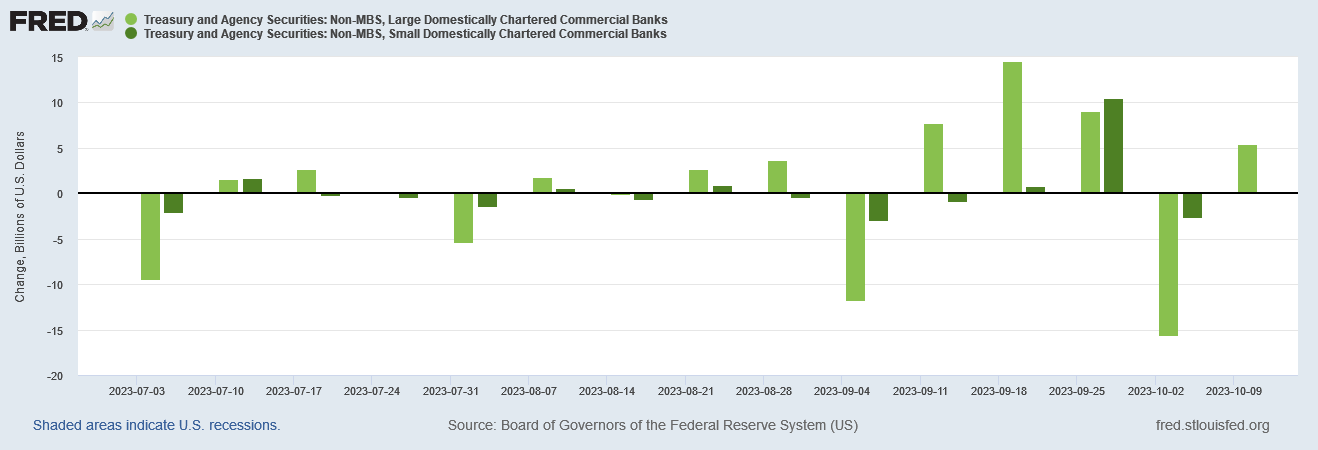

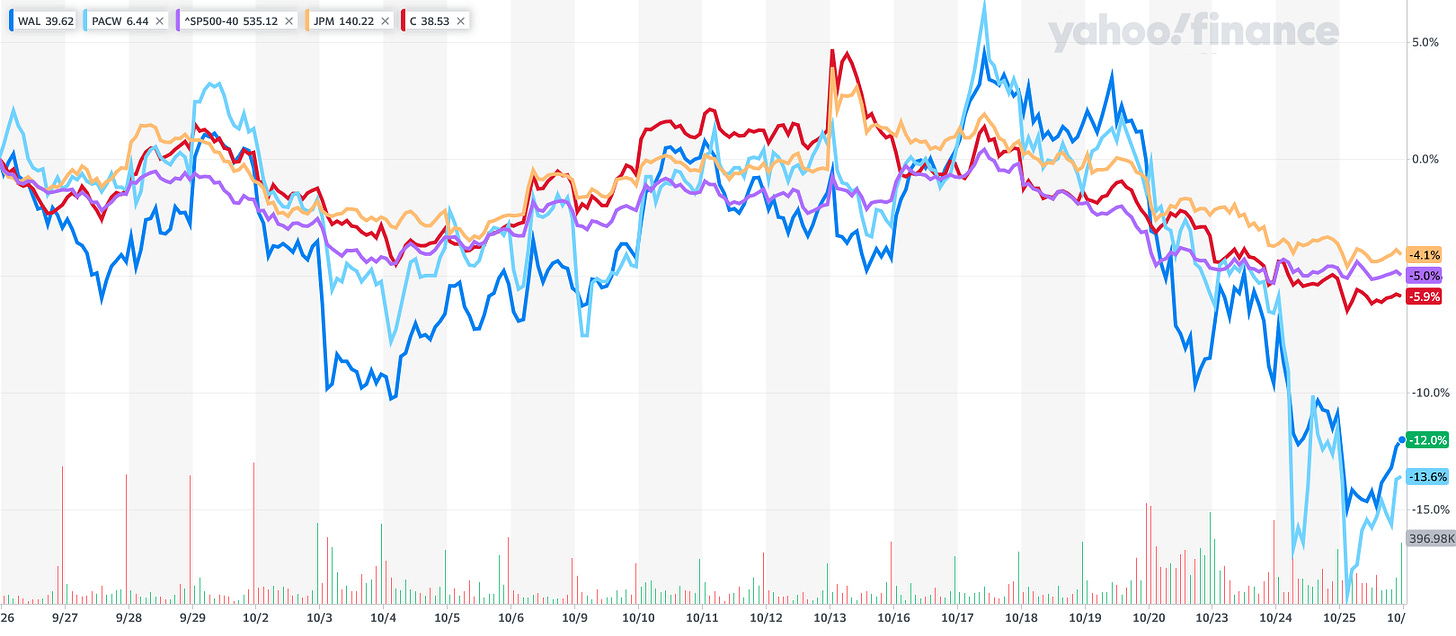

Yet even with Treasury yields, Wall Street is failing to look beyond the headlines. Wall Street is not looking for reasons why banks, after reducing their portfolios of both Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities since July of last year, not only stopped selling off Treasuries but actually began buying them in recent weeks.

In a rising interest rate environment, unwinding positions in debt instruments makes sense, because such investments can only lose value—older securities are always going to be worth less than newer securities with higher yields. Yet despite the increase in Treasury yields, banks have been increasing their holdings of such assets.

This despite such bonds been shedding value since the beginning of the year.

Not all banks have reversed their selling patterns on Treasuries. Smaller banks have, for the most part, continued to reduce their holdings of non-MBS securities.

Larger banks, however, have been buying in recent weeks. Curiously, Wall Street is not punishing large banks for their apparently bad investment choices, as JP Morgan and Citi have fared better in the market than Western Alliance and PacWest—two smaller banks who have been viewed as potential next banking dominoes to fall.

Why are larger banks buying assets which are assured of losing money? Wall Street hasn’t asked that question. If history is any guide, it won’t—not until it’s too late and another banking and liquidity crisis is unfolding.

The “real story” surrounding rising Treasury yields that is not getting proper attention either in the corporate media or in the marketplace is that Wall Street, and the banks especially, are apparently choosing of late to ignore the rising market yields, moving money into securities that are guaranteed to lose value.

If money-losing Treasury investments are the “best bet” large banks can make with depositor cash, all other investment options must be on track to lose even more money, relatively speaking. Regardless of what assets might be involved with those other options, for bulking up on Treasuries to be the best investment choice under current conditions means all other assets besides Treasuries are approaching a market meltdown.

In other words, larger banks arguably are anticipating a market crisis of some sort in the near future, and are moving funds to where they will suffer the smallest loss.

Is this a sign that commercial real estate is about to implode?

Is this an indicator that residential real estate is about to become a fresh financial crisis, pushing the federal government to recklessly intervene?

There is no way to know for certain until such events actually transpire. Yet what is certain is that banking health in this country has been deteriorating for quite some time. What is also certain is that Wall Street has largely been turning a blind eye towards that deteriorating health, and to the continuing questionable investment choices being made by banking officers—and by banking officers at larger banks especially.

There is no way to tell when the catalyzing event will occur that will trigger the next financial crisis, but rising Treasury yields are priming the banking sector for that next financial crisis—and once again Wall Street is not doing anything to get out of harm’s way.

Maybe it is dawning on the smaller 'regional" players that they won't be in the favored 500 million people that are going to be allowed to live. No, that's crazy talk, just yet.

Still, "the world wonders." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_world_wonders

Perhaps it’s a “controlled demolition” rather than a crash. Since Larry Fink took over the Fed, things have been unnatural. Almost like someone is making sure the economy doesn’t crash, but instead certain people continue to make money .