Some Genuine Good News On Inflation. But...?

Is The US Merely Swapping Inflation For Deflation?

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: The May Consumer Price Index Summary report is, by and large, good news. Consumer price inflation is moving in mostly good directions.

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) rose 0.1 percent in May on a seasonally adjusted basis, after increasing 0.4 percent in April, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 4.0 percent before seasonal adjustment.

These numbers are undeniably good news. Overall, this is a good inflation report.

Consumer price inflation is cooling year on year at both the headline and core levels—enough so that core inflation finally broke below the band it has been within since December of 2021.

Headline consumer price inflation cooled significantly month on month, even as core inflation ticked up month on month.

Even shelter price inflation, a primary driver of core inflation, is showing signs of easing.

While core inflation is still inching up month on month, shelter price inflation is decreasing month on month, with the magnitude of monthly shelter price increases beginning to converge with core inflation.

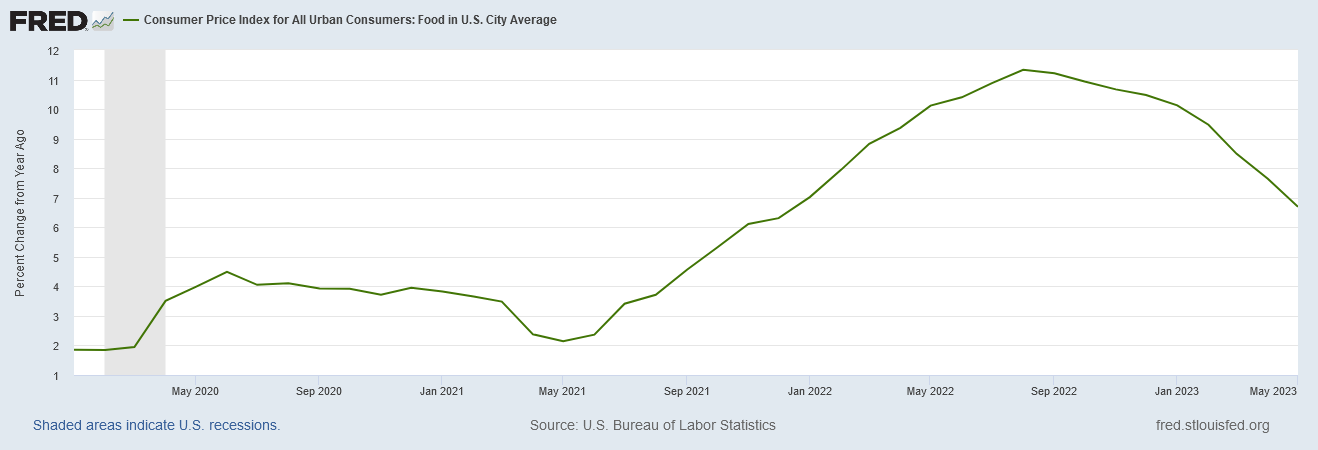

Food price inflation is the lowest it has been since December 2021.

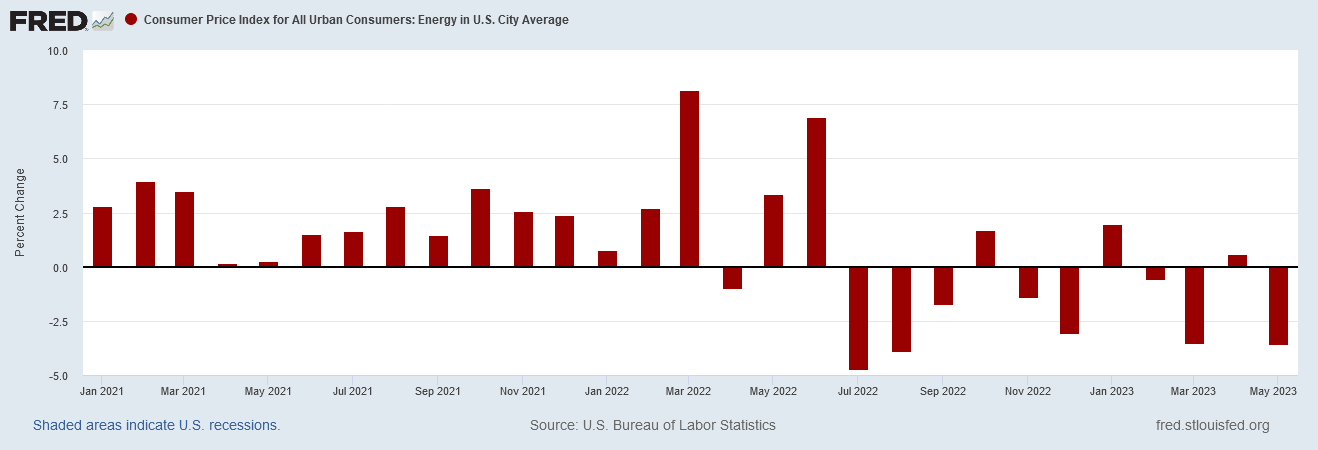

Energy price deflation (prices are falling in absolute terms) showed the largest price decrease since June of 2020.

As a result of this price deflation, energy is trending back towards pre-pandemic price levels, being now 26.7% higher than at the start of the government-ordered recession.

All of these trends are undeniably positive. Even more important, these improvements in consumer price inflation trends come just as the Fed’s FOMC commences its June meeting, where they will decide whether or not another federal funds rate hike is in order. These positive trends give the Fed decent arguments against another rate hike this month.

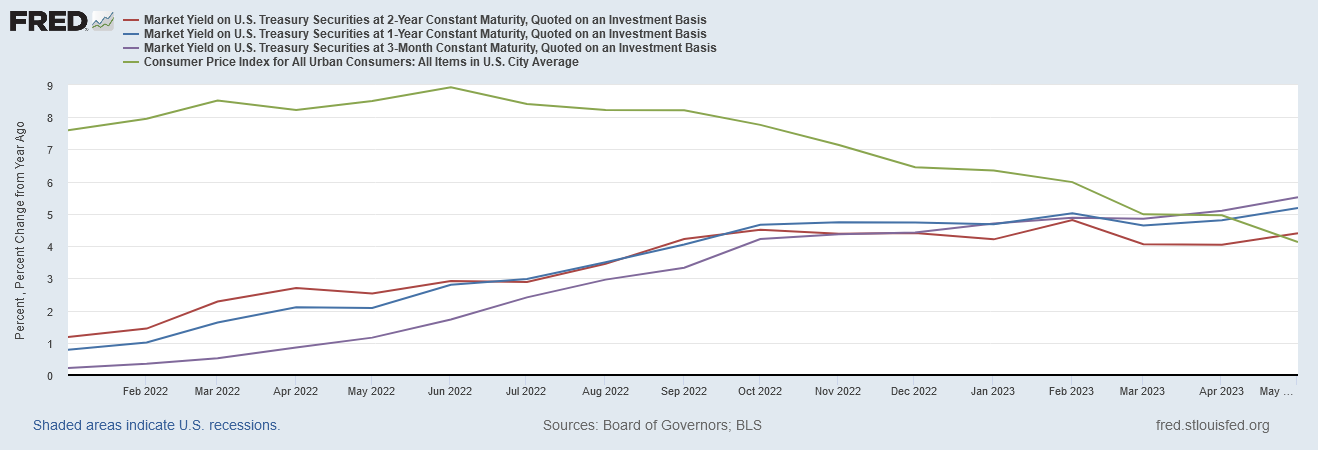

There is an additional argument against further rate hikes at this time: short-term Treasury yields have by and large moved above the year on year consumer price inflation rate, moving real interest rates (yield minus inflation) into positive territory for the first time in years.

Barring twin reversals in both inflation and interest rates, interest rates are now able to send a true cost of capital price signal. Further goosing of interest rates—already of minimal or no benefit—would do little if anything to improve that signal.

Yet we should be mindful that even this positive inflation report is not an unalloyed good. There are warning signs that inflation might not yet be done tormenting consumers.

While consumer price inflation is easing year on year and month on month, core inflation has been ticking upwards for the past few months.

Also of concern: core inflation has never been below 0.3% month on month since September of 2021.

Additionally, food price inflation ticked up month on month, even as it declined year on year.

As with core inflation, this is the third month food price inflation has risen month on month.

These rises are warning signs that inflation may very well reverse course and move higher again in coming months. While this inflation report does show inflation has greatly receded from its 2022 peaks, inflation cannot be presumed to be contained and on a glide path back to the desired levels below 2% year on year.

The other set of warning signals is potentially even more alarming: the disinflationary trend could turn into an extended deflationary trend, sending the economy into a Japan-style period of stagnation. We should not overlook the reality that the Fed’s rate hike strategy is broadly similar to that employed by the Bank of Japan in the early 1990s, with largely similar impacts on money supply growth, which derailed the once vibrant Japanese economy, leaving it in a stagnant and sclerotic state which even the radical treatment of “Abenomics” has failed to reverse.

Is the US economy on course for a similar fate?

While it is far too soon to say with certainty that the US is locked in on a course of “Japanification”, there nevertheless are some crucial red flags that must not be overlooked.

The most obvious deflationary red flag is the fact that energy prices are already in deflation, and have been since July of last year.

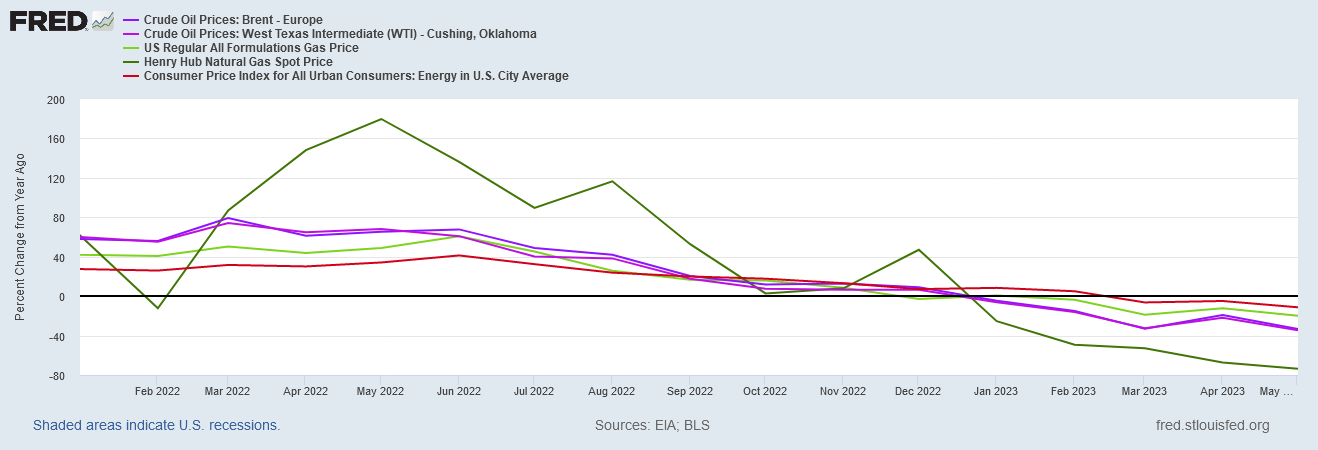

The price declines in energy are across the board. Not only is energy price deflation at -11.3% year on year, but all major energy price elements—Brent crude spot price, West Texas Intermediate spot price, US gasoline spot prices, and natural gas spot prices—have all posted price declines exceeding the energy price deflation mark.

While these downward trends are thus far a positive in that they are returning energy price levels to what they were before the pandemic, the lockdowns, and the start of the current inflationary cycle, we must still ask ourselves how much farther energy prices will fall. Falling to pre-pandemic price levels will be apprehended by most consumers as a net good, but if prices keep falling past that the consequences will not be quite so benign.

It is because of this broad downward trend in energy prices that OPEC has been repeatedly stymied in its efforts to establish a floor price for oil and stabilize oil prices through production cuts.

Not only are these downward price trends taking place on a global scale, but OPEC’s repeated production cuts have failed to have any demonstrable impact on energy prices. Softening demand keeps pushing oil prices down even as OPEC attempts to remove production from the market.

Where is the floor price on oil? At this point we really cannot say.

Nor are the warning signals confined to energy. Several components of the Producer Price Index data set—widely viewed as a leading indicator for consumer price inflation—have either plateaued or begun to trend downward.

If these trends are leading indicators for where consumer price inflation is headed, then we may reasonably expect broad based declines in consumer price inflation in the coming months.

With PPI trends either flat or declining, it is quite possible the consumer price index will continue to rise ever more slowly. If the CPI disinflationary trend goes far enough, however, disinflation could become deflation. We have seen this happen in Japan, and we are seeing it unfolding as well in China.

With China already showing increasing signs of deepening and persistent deflation, does the same fate await the global economy overall, and the US economy by imputation?

As was the case with Japan in the 1990s, deflation is not likely to be readily identified except in hindsight. We will not know if that is what will happen to the US economy until it has already happened.

Ideally, the Fed will tread very carefully with its monetary policy, for Japan also teaches us that too much tightening too quickly has the potential to choke off economic growth and sap economic momentum, to where a quick bounce back after reversing on interest rates and monetary “stimulus” becomes impossible. However, Japan’s recent economic history also forces us to consider the likelihood the Federal Reserve has already tightened “too much”, and we may already be heading into our own “lost decade” of economic stagnation and weakness.

The failure of Japan’s “Abenomics” to restore the country to economic vibrancy is a blunt testament to the limitations of government policy to program economic success. China’s ongoing spiral into Japanification is another testament as yet ongoing.

Whether the Fed can legitimately claim credit for the improvements in consumer price inflation to date is immaterial. If Jay Powell wants to take a victory lap over 4% inflation so be it. However, if Jay Powell and the Fed are responsible for pushing inflation down this far, should this current disinflationary trend turn into a deflationary one Jay Powell and the Fed will likewise be responsible for the Japanification of the US economy.

Even if Powell is not responsible for pushing inflation down this far, with banking and liquidity crises already happening, a Powell policy error now can all too easily tip disinflation into outright deflation.

It is far too soon to say with certainty if the US is heading into its own “lost decade”. It is hardly too soon to point out that risk is real, and that risk is growing.

Just as too much of anything is a bad thing, too much disinflation—to where disinflation becomes deflation—is just as bad if not worse than too much inflation. It will be no policy success of any kind if Powell succeeds in pushing the US from the one extreme to the other.

Another excellent analysis, succinctly putting all the pieces of the big picture together. You give us a comprehension that we’d be hard-pressed to find anywhere else, Mr. Kust!

In the early days of OPEC, the money pouring in was gravy to be lavished on any delights they wanted to have. But now virtually all of the members of OPEC are completely dependent on that oil for their political survival. So I imagine that OPEC leaders are thinking, hmm, cutting production didn’t shore up prices, and demand is falling and likely to fall further - what can we do to ensure our regime’s survival? Sabotage a Russian production facility, and make it look like an ordinary part of their war? Undercut the regime of a politically weaker OPEC member - such as Venezuela’s Maduro - in ways that kick it out of the picture? What do you think, Mr. Kust - any speculation on OPEC’s moves in their desperation?