Stagflation: The Rise And Fall Of Consumer Prices

PCE Report Once Again Awash In Mixed Signals

If there is one common theme within my postings it is this: never accept anything at face value. When it comes to the “official” economic data being released by the scorekeepers within our own government, that is especially so.

On the surface, the October, 2023, Personal Income and Outlays Report is good news, showing inflation continuing to retreat, with increases in both nominal and real disposable incomes.

Personal income increased $57.1 billion (0.2 percent at a monthly rate) in October, according to estimates released today by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (tables 2 and 3). Disposable personal income (DPI), personal income less personal current taxes, increased $63.4 billion (0.3 percent) and personal consumption expenditures (PCE) increased $41.2 billion (0.2 percent).

The PCE price index increased less than 0.1 percent. Excluding food and energy, the PCE price index increased 0.2 percent (table 5). Real DPI increased 0.3 percent in October and real PCE increased 0.2 percent; goods increased 0.1 percent and services increased 0.2 percent (tables 3 and 4).

Surely it must be counted as good news that consumer price inflation is down yet again, with the Fed’s inflation Holy Grail of 2% year on year inflation now coming into view?

Perhaps it is good news. However, the report says a good deal more than this, and contains a good deal more data than this, and that data is not necessarily at all good. Naturally, I’m not going to take the BEA report any more at face value than I took the GDP data the other day (plus if I did that I’d have no reason to write about it!).

Accordingly, let’s delve into what the corporate media chooses not to examine in the BEA data.

It comes as no surprise that the corporate media is dutifully parroting the official narrative of “inflation is coming down."

Inflation continued to cool in October.

The Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Index grew 3% year over year for the month, down from 3.4% in September and with expectations. "Core" PCE, which excludes the volatile food and energy categories, grew 3.5%, down from 3.7% from the month prior and in line with what economists surveyed by Bloomberg had expected.

Month-over-month, core PCE rose 0.2% in October, down from 0.3% in September.

Together with the GDP estimates released the day before, the PCE report is being touted as proof the economy is moving towards 2% year on year consumer price inflation, just as the Fed has intended all along.

The quarterly reading for Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) showed core prices, which exclude volatile categories like food and energy, grew at a 2.3% pace during the third quarter, down from an initial reading of 2.4%. The release showed inflation continues to cool towards the Federal Reserve's long-run goal of 2% inflation.

This, of course, dovetails neatly with the corporate media messaging surrounding the earlier Consumer Price Index Summary report for October, which said nearly the exact same thing.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) showed prices were flat over last month and rose 3.2% over the prior year in October, a deceleration from September's 0.4% monthly increase and 3.7% annual gain in prices.

Economists had expected prices to increase 0.1% month-over-month and 3.3% year-over-year, according to data from Bloomberg.

Certainly Wall Street was willing to go along with the narrative, as the Dow Jones rose over 520 points on the day, hoping that the headline numbers will persuade the Fed to come down on interest rates sooner rather than later.

The sharp fall in inflation since another closely watched barometer — the Consumer Price Index — peaked at 9.1% in June of 2022 has raised investor hopes that the Fed will shelve its efforts to cool economic growth by pushing up borrowing costs. Some Wall Street analysts now forecast that the central bank could move to trim its benchmark interest rate by the middle of 2024.

Wall Street analysts are also increasingly confident that the U.S. will dodge a recession despite the Fed's aggressive campaign to quash inflation. Although job growth has slowed — pushing the nation's unemployment rate to 3.9%, the highest level since January of 2022 — most economists now think the labor market will avoid the kind of steep downturn that historically has followed rapid increases in interest rates.

However, what was missing from the coverage of the Consumer Price Index Summary is the same thing missing from the Personal Income and Outlays Report: an awareness of growing signs of either outright deflation or that cruel mix of deflation and inflation broadly known as stagflation.

Closer scrutiny of the October PCE report shows that we are seeing the same muddled signals on prices, disinflation, deflation, and inflation.

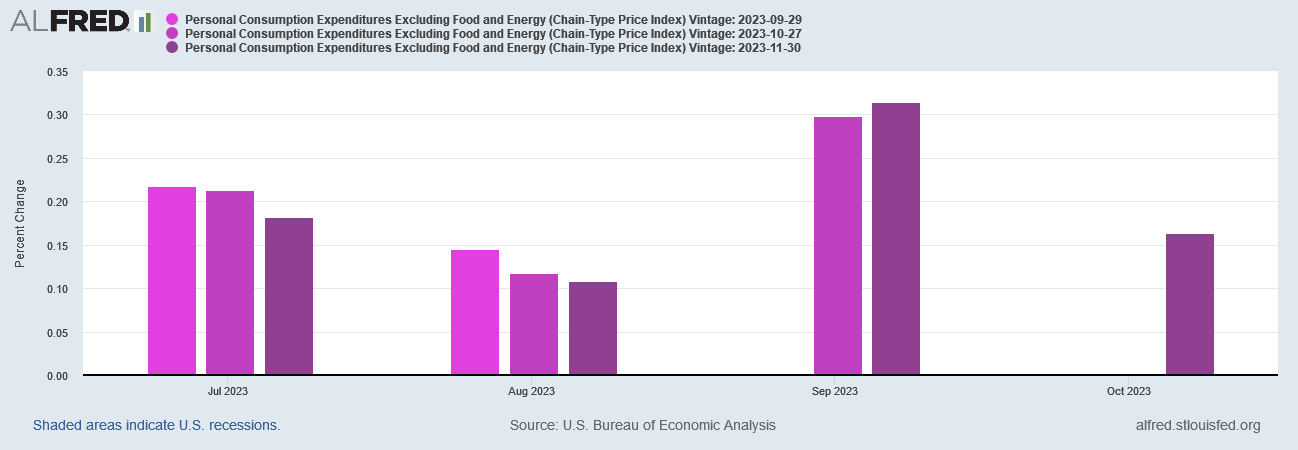

We should pause to note first the impact of revisions on the data landscape. Lost in the media hooplah surrounding the declining inflation metrics is the fact that the BEA has revised historical consumer spending downward repeatedly in recent months.

Personal Consumption Expenditures overall were revised down in both July and August, meaning the level of actual economic activity was noticeably less than first reported.

Even core inflation—the PCE Price Index with food and energy stripped out—has seen substantial revisions after each release.

It is worth notng also that for both headline and core consumer price inflation, the September data saw upward revisions. However, overall, personal consumption expenditures have turned out to be perceptibly less than first reported. While the corporate media is doggedly promoting a narrative of a growing economy, the evolution of the official statistics, with its downward trend in overall consumption, cuts pretty significantly in the direction of a shrinking economy. Certainly we are facing less rather than more consumption.

Declining consumption is unquestionably the nature of the data regarding expenditures on durable goods, which has been printing outright deflation for several months now.

Unlike the overall headline and core inflation metrics, the data on durable goods purchases has held up to scrutiny over time.

The same has been true for the consumption of non-durable goods.

There have been marginal changes in the historical data, but overall the data on non-durable goods has also withstood scrutiny over time.

Where the revisions have been the most impactful has been in the area of services inflation. There we see the revision pattern for both headline and core inflation emerge.

With services being the only area showing persistent price inflation rather than outright deflation, the downward historical revisions for services expenditures shows consumption has been significantly weaker than has been first reported.

Viewed across all three expenditure areas, the PCE data continues to display a stagflationary mix of deflation, disinflation, and stubborn inflation.

Since June of this year, durable goods prices have been in outright deflation, with non-durable goods flirting with deflation while trending very close to the zero bound on inflation. At the same time, the shifts in services pricing have been far more muted both in the rise and the decline.

Viewed another way, since 2021, virtually all of the fluctuations in consumer price inflation per the PCE Price Index has been within goods consumption—and most goods consumption is now on the decline (the polar opposite of what one expects if there is economic growth).

When we look at the month on month percent changes to the PCE Price Index, we see the decline in goods consumption is both a near-term and long-term trend.

Absent a momentary surge in consumption of non-durable goods, the prevailing trend for goods consumption has been one of deflation and decline throughout 2023.

What the corporate media fails to acknowledge in this, however, is that the relative stubbornness of services inflation means that year on year core inflation remains above headline inflation even as the numbers continue to fall.

Once again, the greatest contributor to the decline of headline inflation has been energy price deflation, which even recent spikes in crude oil prices have not been able to fully eliminate.

In recent months, this trend has been helped along by significant year on year food price disinflation as well, which is now trending below the headline inflation metric (finally!).

This particular trend is unlikely to last, as month on month food price inflation has been printing above core inflation and in October printed above headline inflation as well.

The net effect is that food prices will continue to be a shopping headache for most people going into the holiday season.

Yet even with the rosy view of consumer price inflation per the PCE data, one glaring reality remains unaltered: prices are still considerably higher relative to incomes than they were at the beginning of 2021.

Not only have real disposable incomes declined since 2021, the year on year increases to nominal and real incomes have even recently only just kept pace with price increases, after lagging through most of 2021 and 2022.

For 2023, the month on month changes to real disposable personal income have fallen short of the increases in consumer prices in six out of ten months.

This after losing ground since early 2021.

While incomes are technically rising at the moment, according to the data, the reality is that, overall, they have been stagnant to declining with respect to prices. People’s paychecks are still being taken over by inflation even with the inflation numbers themselves printing well below their summer 2022 peaks.

Is the BEA data good economic news? Ultimately, no, it is not. While the PCE report is not apocalyptically bad news, we are nevertheless still presented with a dysfunctional and distorted economy, just as we have been witnessing since the end of the Pandemic Panic Recession.

While some parts of the economy are in outright deflation—and worryingly so—other parts are still showing significant inflation, and have proven fairly impervious to the Fed’s interest rate hike strategy.

To the extent that we have any forward visibility on prices, the outlook is deflationary, and not merely disinflationary.

The October PCE report does nothing to alter any of this. We have inflation, we have deflation, and so we have stagflation—and stagflation is the best outcome we can extrapolate from the available data.

The corporate media dutifully tout the PCE numbers as signs of a strong and resilient economy while intimating the Fed has been successful in mitigating consumer price inflation. The “official” narrative remains one of an economy avoiding recession while prevailing against inflation.

The reality is that the economy is and has been sick and increasingly sclerotic, while the Fed’s manipulations of interest rates have not accomplished a damn thing. The reality is that people are earning less now than before, while paying more to buy less. The reality is an economy still very much in recession in spite of what the official data purports to project.

Bring back Trump!

"I had money in my pocket with Trump." Spoken by members of the Bronx (83% for Biden in 2020).