As I noted somewhat flippantly last night in a guest write-up for Wholistic News, “Monkeypox is baaack, and the WHO wants you to be afraid!”

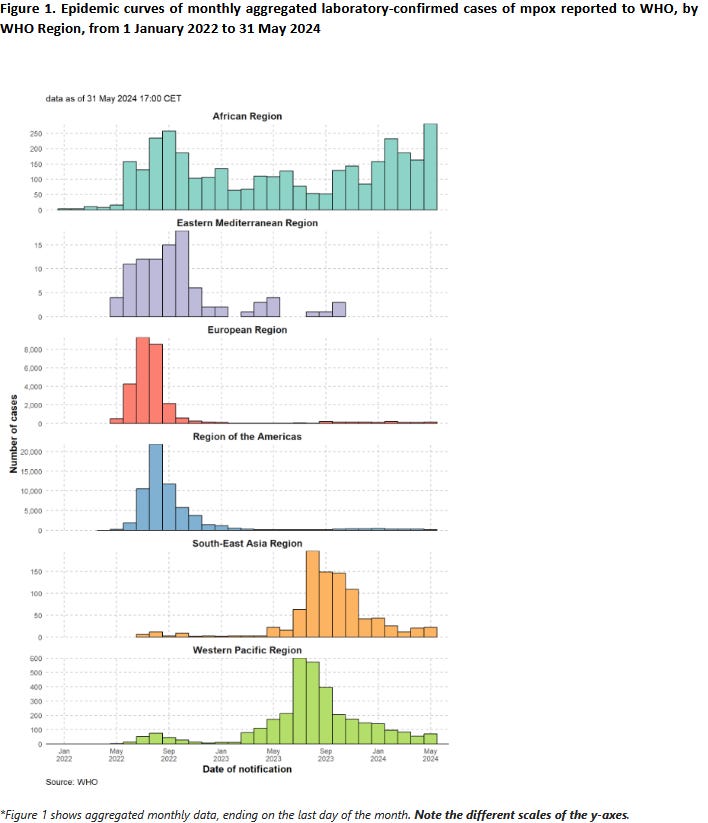

The reality is that monkeypox has never actually gone away. However, the reality is also that the disease is concentrated in Africa—where it has always been—and there is little indication of it spreadhing beyond that continent.

It is a testament to the extent which “Science™” is no longer capable of serious critical thinking that at one time was a prerequisite for “good science” and good science reporting that ScienceAlert gave its write-up of the Monkeypox outbreak this headline.

Certainly their lead paragraphs give the situation in Africa a dire aspect.

Alarmed by the surge in mpox cases, the Africa Centres for Disease Control has taken the unprecedented step of declaring the outbreak sweeping through African countries a continental public health emergency.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is also meeting to decide whether to trigger its highest global alert level over the epidemic.

These moves come after a virulent strain of the disease spread rapidly to 16 countries and six new countries were affected in 10 days.

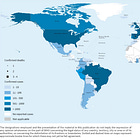

There have been 15,132 mpox confirmed cases in Africa since the beginning of 2024. Some of the countries affected are Burundi, Cameroon, Congo, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, Uganda and Kenya.

Certainly, 15,000+ confirmed cases of monkeypox in Africa since the beginning of the year is cause for concern.

Still, we should not overlook a fundamental hypocrisy at play here: While it took 15,000+ cases in Africa to become a problem, in 2022 it only took just over 100 cases outside of Africa to scare everybody.

Beginning around 13 May 2022, cases of monkeypox infection have been reported to the WHO from countries outside the region in Africa where the disease is known to be endemic, and with no established travel links to that region. As of 21 May, all confirmed cases of monkeypox within this current outbreak have been identified as belonging to the less severe West African clade, which has a mortality rate of around 1% (the Central African clade has a mortality rate of 10%).

Side note: media reports which reference a 10% mortality rate are referencing the Central African clade, not the West African clade,which is the one currently in global circulation. This subtle factual error is the result of considerable media exaggeration of the severity of the outbreak.

As of this writing, there are 109 confirmed cases of monkeypox, 3 probable cases, and 92 suspected cases. As the outbreak is ongoing, these numbers will change substantially day by day.

Indeed, as Monkeypox Mania gripped the world during the summer of 2022, Africa was studiously and even deliberately ignored, as close study of the data revealed at the time.

Including suspected cases, there are 2,674 monkeypox cases within Africa and 11 “confirmed” deaths as of the most recent weekly bulletin (Bulletin 32, 1-7 August 2022). The confirmed attribute is relevant because up through WHO-Africa’s Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies Number 30 (18-24 July 2022), suspected deaths were being reported as well, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo had 65 suspected deaths as of that report period. Reporting after that only counted confirmed deaths.

Intriguingly, Weekly Bulletin 31, the first bulletin focusing on confirmed deaths (and thus dropping the DRC deaths to 0), came right after the WHO declared monkeypox a Public Health Emergnency of International Concern on July 23.

Including all suspected cases there are reports of nearly 3,000 cases of monkeypox in Africa, and over 100 deaths just in 2022.

At least 2,947 monkeypox cases have been reported in 11 African countries this year, including 104 deaths, but most of the cases reported are suspect ones because the African continent also lacks enough diagnostic resources for thorough testing, the Africa CDC director said.

It is worth noting that at least 81 people died from suspected monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during 2021, another 229 died in 2020, and 107 more died in 2019.

Since epidemiological week 1 up to week 49 in 2021, 2 898 cases have been reported with 81 deaths (CFR 2.8%). Between epidemiological week 1 and week 53 of 2020, a total of 6 257 suspected cases including 229 deaths (CFR 3.7%) were reported in 133 health zones from 17 out of 26 provinces in the country. During the same period in 2019, 5 288 suspected cases and 107 deaths (CFR 2.0%) were reported in 132 health zones from 18 provinces. Overall, there was a regressive trend from epidemiological week 33 to 53 of 2020 (276 cases vs 76 cases)

However, despite having the most confirmed deaths from monkeypox in 2022, as well as hundreds of suspected deaths just in the DRC since 2019, Africa has at this time zero doses of the Jynneos smallpox vaccine, which is currently the only FDA-approved vaccine for monkeypox.

Not only was the much higher death toll in Africa being studiously ignored, the WHO even fudged the numbers to minimize the African outbreak.

That history is essential context, because to hear the Director-General of the Africa CDC H.E Dr. Jean Kaseya tell it, as he did at the closing of his remarks announcing that monkeypox was now a Public Health Emergency of Continental Security (PHECS), the virus was unexpected.

Mpox may have taken us by surprise, but it will not defeat us. Together, we will rise above this challenge. Together, we will protect our people, our future, and our continent.

Exactly how the Africa CDC can claim to be surprised by monkeypox in August when it was tracking the cases since at least the springtime is a mystery, especially as in March alone there were 181 monkeypox cases reported in all of Africa.

Pity the WHO neglected to notify Africa CDC of this data, otherwise Dr. Kaseya might have acted a bit sooner, given the emphasis he placed on swift and decisive action during his PHECS remarks.

We declare today this PHECS to mobilize our institutions, our collective will, and our resources to act—swiftly and decisively. It empowers us to forge new partnerships, to strengthen our health systems, to educate our communities, and to deliver life-saving interventions where they are needed most.

But declarations alone will not suffice. Words must be matched with deeds.

And today, I commit to you that Africa CDC will lead this fight with every resource at our disposal. Together with our partners, we will deploy experts, bolster our laboratories, and enhance in-country and cross-border surveillance systems. We will work with governments, international partners, and local communities to ensure that every African, from the bustling cities to the remotest villages, is protected.

The reality of monkeypox in Africa is that the cases have been steadily climbing all year, even as they have been dropping in other parts of the world.

Calling this outbreak “new”, as Vox does, significantly understates the actual disease situation in Africa.

In response to new and resurging mpox outbreaks in multiple African countries, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention declared mpox a continent-wide public health emergency Tuesday. Although many countries outside of Africa rapidly contained an mpox pandemic that began in 2022, large outbreaks continued unabated in west and central Africa. And now, a deadlier strain is spreading across borders in Africa.

Not only is monkeypox not “new” in Africa, the current outbreak does not qualify as “new”.

The reality is that this outbreak has been building for quite some time—one could even argue this outbreak predates the global STD outbreak of 2022. The more virulent strain of monkeypox which has emerged in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was found in patient samples taken late last year, and was reported in early May.

An analysis of patients hospitalized between October and January in Kamituga, eastern Congo, suggests recent genetic mutations in mpox are the result of its continued transmission in humans; it’s happening in a town where people have little contact with the wild animals thought to naturally carry the disease.

“We’re in a new phase of mpox,” said Dr. Placide Mbala-Kingebeni, the lead researcher of the study, who said it will soon be submitted to a journal for publication. Mbala-Kingebeni heads a lab at Congo’s National Institute of Biomedical Research, which studies the genetics of diseases.

It was in early May the DRC saw a significant uptick in monkeypox cases, according to the Africa CDC—the same Africa CDC which was taken by “surprise” by monkeypox just this week.

Among major news outlets, only CNN framed the outbreak factually, including identifying that the ongoing surge in cases is being driven by the more virulent clade 1b of the virus.

The World Health Organization on Wednesday declared the ongoing mpox outbreak in Africa a global health emergency.

WHO convened its emergency mpox committee amid concerns that a deadlier strain of the virus, clade Ib, had reached four previously unaffected provinces in Africa. This strain had previously been contained to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Independent experts on the committee met virtually Wednesday to advise WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on the severity of the outbreak. After that consultation, he announced Wednesday that he had declared a public health emergency of international concern — the highest level of alarm under international health law.

Broadly, Monkeypox strains are organized into two “clades”, clade I and clade II. The strain that was behind the 2022 global STD outbreak of monkeypox was a clade II strain—which is by far the less lethal of the two clades.

Clade 1b is more lethal still. It emerged last September in the eastern DRC, before being sequenced and identified as a distinct sub-Clade in April. It should be noted that the researchers who identified the strain called for “swift action” at that time.

The researchers said sustained spread in the Kamituga region raises concerns because of its poor healthcare infrastructure, frequent population travel to Rwanda and Burundi, and the fact that a number of the sex workers in Kamituga are foreigners and frequently return to their home countries.

So far, no cases involving the new lineage have been reported outside of the DRC. The group warned, however, "Given the recent history of mpox outbreaks in DRC, we advocate for swift action by endemic countries and the international community to avert another global mpox outbreak."

From April to August for the WHO and Africa CDC to push the panic button on monkeypox apparently is what passes for “swift action”.

Still, better late than never, right? The WHO and Africa CDC might have been tardy in sounding the alarm on monkeypox, but now that they have done so they can get vaccines out to everyone and stop the disease in its tracks….can’t they? After all, we’re not talking about faux mRNA inoculations, but actual “vaccines” that have been actually tested. So surely they work, don’t they?

About that….

It is true that JYNNEOS™ was approved for monkeypox vaccination in 2019.

As I noted during the 2022 outbreak, however, it had not been clinically tested against monkeypox.

The vaccine that is being urged on people, JYNNEOS™ is a live, non-replicating, vaccinia virus vaccine originally designed as a smallpox vaccine. While it is approved for vaccination against monkeypox, its efficacy as a monkeypox vaccine has never been rigorously tested or studied.

From the CDC Monkeypox vaccination web page (emphasis mine):

Because Monkeypox virus is closely related to the virus that causes smallpox, the smallpox vaccine can protect people from getting monkeypox. Past data from Africa suggests that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox. The effectiveness of JYNNEOS™ against monkeypox was concluded from a clinical study on the immunogenicity of JYNNEOS and efficacy data from animal studies.

Moreover, JYNNEOS™ is only marginally better than the ACAM2000 vaccine it was intended to replace1.

For the first and second questions, regarding recommendation for JYNNEOS as an alternative to ACAM2000 for primary vaccination, the systematic review identified three randomized controlled studies and 15 observational studies including a total of 5,775 subjects. After considering geometric mean titers and seroconversion data together, the Work Group had moderate (level 2) certainty that JYNNEOS provides a small increase in disease prevention compared with that provided by ACAM2000.† The Work Group estimated with low (level 3) certainty that fewer serious adverse events occur following the JYNNEOS primary series compared with ACAM2000 primary vaccination, and that fewer events of myopericarditis occur after JYNNEOS primary series than after ACAM2000 primary vaccination. Based on the results from the GRADE assessment and EtR framework,§ ACIP unanimously voted in favor of the JYNNEOS vaccine as an alternative to ACAM2000 for primary vaccination.

Additionally, the vaccine protection does not last long. In environments where monkeypox is endemic (i.e., Africa), the US CDC recommendataion in 2022 was for booster shots every two years.

In addition, persons who received the 2-dose JYNNEOS primary series and who are at ongoing risk¶¶¶ for occupational exposure to more virulent orthopoxvirus e.g., Variola virus and Monkeypox virus), should receive a booster dose of JYNNEOS every 2 years after the primary JYNNEOS series

In practical terms, JYNNEOS™ was reviewed for efficacy during the 2022 outbreak and found to be only around 66% effective at preventing infection2.

Among 2193 case patients and 8319 control patients, 25 case patients and 335 control patients received two doses (full vaccination), among whom the estimated adjusted vaccine effectiveness was 66.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 47.4 to 78.1), and 146 case patients and 1000 control patients received one dose (partial vaccination), among whom the estimated adjusted vaccine effectiveness was 35.8% (95% CI, 22.1 to 47.1).

As it turned out, for the global STD variant of monkeypox, the 2022 outbreak ultimately was contained not by vaccination but by behavior modification3.

When we overlaid North American Rt estimates alongside the cumulative percentage of high-risk individuals in the USA with mpox vaccine-derived immunity (for description of the data and definitions, see STAR Methods, under data sources), we found that Rt began declining prior to initiation of vaccination in the US (Figure 6A). Vaccine-induced immunity was estimated via a 2-week lag since the date of vaccination. North American Rt estimates fell below one near mid-August 2022, when the cumulative percentage of high-risk individuals with vaccine-derived immunity was less than 8%. Under a susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) model of infectious disease dynamics, vaccine-derived immunity impacts disease transmission by removing individuals from the susceptible population in a linear fashion. Before there was any mpox vaccine-derived immunity in the US, North American Rt peaked at 1.49

In other words, the potential for a mass vaccination campaign in Africa to contain the monkeypox outbreak even if the resources were marshalled is not great. The WHO and Africa CDC are most likely looking at non-pharmaceutical interventions to disrupt the spread of the disease—interventions that they have been putting off for as long as they have been ignoring the increasing spread of the disease in Africa.

The real health crisis surrounding monkeypox in Africa is, sadly, the same one that Africa faced in 2022—a conspicuous lack of public health bureaucracies and officials giving as much a tinker’s damn about Africa.

In 2022, the global outbreak meant that Africa was at the back of the line for the JYNNEOS™ vaccine.

However, despite having the most confirmed deaths from monkeypox in 2022, as well as hundreds of suspected deaths just in the DRC since 2019, Africa has at this time zero doses of the Jynneos smallpox vaccine, which is currently the only FDA-approved vaccine for monkeypox.

Nor was this accidental. At every turn even the WHO worked to deprioritize Africa with respect to monkeypox response even as it was arguably having the most severe outbreak.

For its part, the WHO has been subtly but persistently working to “memory hole” the unconfirmed “suspected” monkeypox cases in Africa, thereby downplaying the extent of the outbreak in West and Central Africa. The most notable example of this is the decision by the WHO to discard the suspected African cases previously reported from the Disease Outbreak News Bulletin of June 17.

At every turn, a deliberate and demonstrable effort has been made to obscure the distinct African outbreak by subsuming it into the global outbreak, ignoring the multiple differences between the outbreaks to present them as one outbreak rather than two.

Arguably, the 2022 outbreak of monkeypox in Africa—which was demonstrably distinct from the global STD outbreak—has never ended. With varying degrees of intensity it has been ongoing since before the global STD outbreak.

However, unlike the global STD outbreak, the clade 1 and clade 1b strains giving rise to this latest public health emergency carry a significant mortality rate—historically as high as 11%4. As clade 1b has spread in eastern Congo, it has steadily succeeded in claiming lives.

Since January, Congo has reported more than 4,500 suspected mpox cases and nearly 300 deaths, numbers that have roughly tripled from the same period last year, according to the World Health Organization. Congo recently declared the outbreak across the country a health emergency.

The cases in eastern Congo are also significant as they confirm that clade 1 and 1b monkeypox can be transmitted through sexual contact.

Is monkeypox a truly global health crisis?

Ultimately, no. The current outbreak is still within Africa, and while it is spreading it is not spreading globally. While the presence of spread via sexual contact means that cases could spread globally, the fact that the 2022 outbreak was curtailed largely by behaviorial changes among gay men indicates that similar measures would not only be effective again, but there would be less resistance to their implementation.

Monkeypox is an issue for Africa. Africans are getting infected with monkeypox and some Aftricans are dying as a result. Africans have been getting infected with monkeypox for quite some time, and a signficant number of Africans have been dying as a result.

Contrary to the pearl-clutching in ScienceAlert, monkeypox is not on the verge of “exploding” into a pandemic. Even though clade 1b has been shown to spread through sexual contact, it has not, at this time, found a sufficiently promiscuous patient population to infect that would allow it to be readily spread globally.

The sobering reality of monkeypox is that it only becomes a likely global health issue when it becomes largely sexually spread. Monkeypox spread worldwide in 2022 because public health officials refused to acknowledge that fact even as the data was showing unambiguously that it was spreading via sexual contact.

Moreover, while monkeypox can spread via sexual contact, we should not conflate it with historic STDs such as syphilis. Monkeypox infection is relatively short-lived, after which the patient typically enjoys lifetime immunity. Simple abstinence for a time among promiscuous communities of gay and bisexual men was sufficient to tamp down the global outbreak. There is no reason not to presume it would suffice again should monkeypox spread outside Africa.

Is monkeypox a health issue within Africa? Absolutely. It has been since before the 2022 outbreak. The attention that is being globally paid to monkeypox in Africa should have been paid in 2022. If monkeypox in Africa had been confronted then, the WHO would in all probability not be facing a large outbreak of clade 1b monkeypox today.

The real health crisis surrounding monkeypox in Africa is still one of bureaucratic indifference. Sadly, there no reason to believe that is going to change even now. For all the willingness of the public health bureaucrats to posture and pontificate, the one thing they are not willing to do is give a damn.

People in Africa are going to continue to die from monkeypox because of that.

Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for Preexposure Vaccination of Persons at Risk for Occupational Exposure to Orthopoxviruses: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 27 May 2022. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7122e1

Deputy, PhD, N. P., et al. “Vaccine Effectiveness of JYNNEOS against Mpox Disease in the United States.” The New England Journal Of Medicine, vol. 388, no. 26, 2023, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215201.

Paredes, Miguel I et al. “Underdetected dispersal and extensive local transmission drove the 2022 mpox epidemic.” Cell vol. 187,6 (2024): 1374-1386.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.003

Bunge, Eveline M et al. “The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox-A potential threat? A systematic review.” PLoS neglected tropical diseases vol. 16,2 e0010141. 11 Feb. 2022, doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141

There is also the issue of ‘perspective’. How many people in Africa in 2022 died from malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, and other common, endemic diseases? Maybe 100 million+, not to mention health problems such as dysentery and malnutrition. So why doesn’t the WHO panic over those deaths? The WHO, and related scientific interests, fixate on the ‘new’ diseases because that’s how they can get funding, peer recognition, and power.The tropical parts of the world have always endured huge casualties from tropical diseases - and these diseases have never ‘taken over’ the rest of the world. The mosquitoes that spread malaria wouldn’t survive one day of my Minnesota winter.

The power-mad WHO is a ‘cure’ in search of a problem. If there are 3,000 cases of a disease, out of a population of one billion-plus Africans, they are going to try to leverage that into more money and power for themselves. Let’s not fall for it, okay? You’re right, Peter, they don’t care - except about themselves.

This is a stark reminder of the ongoing challenges posed by the monkeypox outbreak, particularly in Africa.

The apparent discrepancy in global responses is a cause for concern, as infectious diseases know no borders and can spread rapidly in the interconnected world. The lack of urgency in addressing the outbreak in Africa, where the disease is endemic, raises questions about global health priorities and the need for equitable responses.

Furthermore, the insufficient testing of the JYNNEOS vaccine against monkeypox adds to the uncertainty surrounding the fight against this disease.