Through The Looking Glass: What The "Experts" Refuse To Acknowledge About Inflation

They Commit The Same Error As The Fed By Failing To Look At And Follow The Data

As regular readers of this Substack already know, I frequently take the Federal Reserve to task over its inflation fighting strategy. For paying subscribers, I have dissected Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s short but blunt Jackson Hole speech.

I have used ongoing inflation trends to highlight the inefficacy of the Fed’s strategy of persistent interest rate hikes.

Yet Jay Powell’s gift for policy error should not blind us to the equally inane cluelessness and refusal to follow the economic data that has become de rigeur among the nation’s academic economists. Case in point: Wharton economics professor Jeremy Siegel’s rant last week that Powell made a major policy error last year by not raising rates then in response to rising commodity prices.

“When we had all commodities going up at rapid rates, Chairman Powell and the Fed said, ‘We don’t see any inflation. We see no need to raise interest rates in 2022.’ Now when all those very same commodities and asset prices are going down, he says, ‘Stubborn inflation that requires the Fed to stay tight all the way through 2023.’ It makes absolutely no sense to me whatsoever,” Siegel said on CNBC’s “Halftime Report.”

What “guru” Siegel won’t see or won’t admit is that the commodity price spikes of 2021 are no more correlated to changes in the money supply than the consumer price inflation Jay Powell is attempting to fight now. Raising interest rates last year very likely would have led to the exact same stagflationary crisis the Fed has presently, and for the same reason: monetary policy is not a primary driving force for the inflation we are seeing today.

Commodity Price Inflation Is Not Consumer Price Inflation

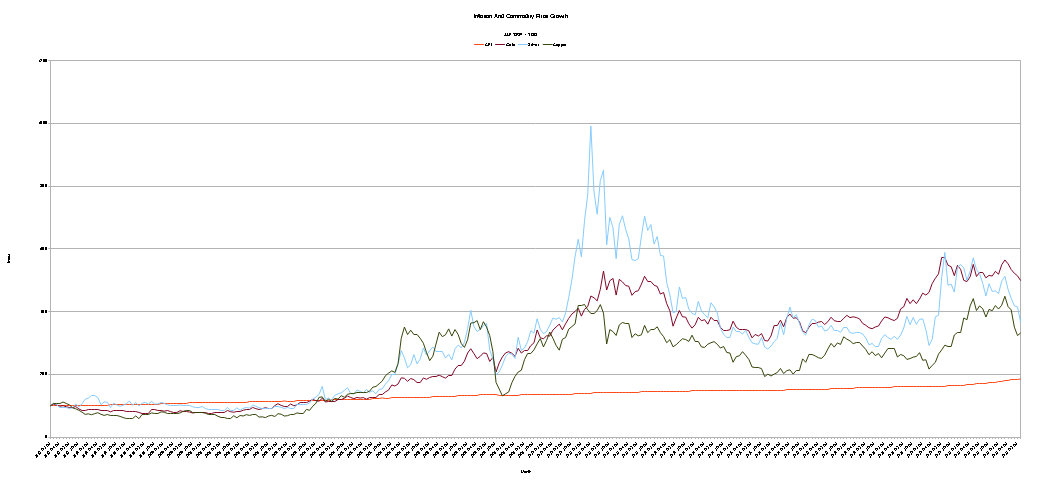

When we look at the historical data1 for money supply growth, consumer price inflation, asset price inflation, and commodity price inflation, a number of presumed and implied equivalences are immediately shown to be false. Let us begin with the most obvious--and obviously incorrect--inflation canard implied by Siegel: that commodity price inflation is the same as consumer price inflation. Simply put, it isn't.

If we index2 the historical values for the Consumer Price Index as well as Gold, Silver, and Copper futures, using January 1997 as the baseline date for each, we immediately see that the movement in commodity price futures is almost entirely independent of change within the Consumer Price Index. It is absurd on its face to suggest that the forces driving consumer price inflation are in all cases the same forces driving commodity price inflation, when the historical data demonstrates that this is not even remotely true.

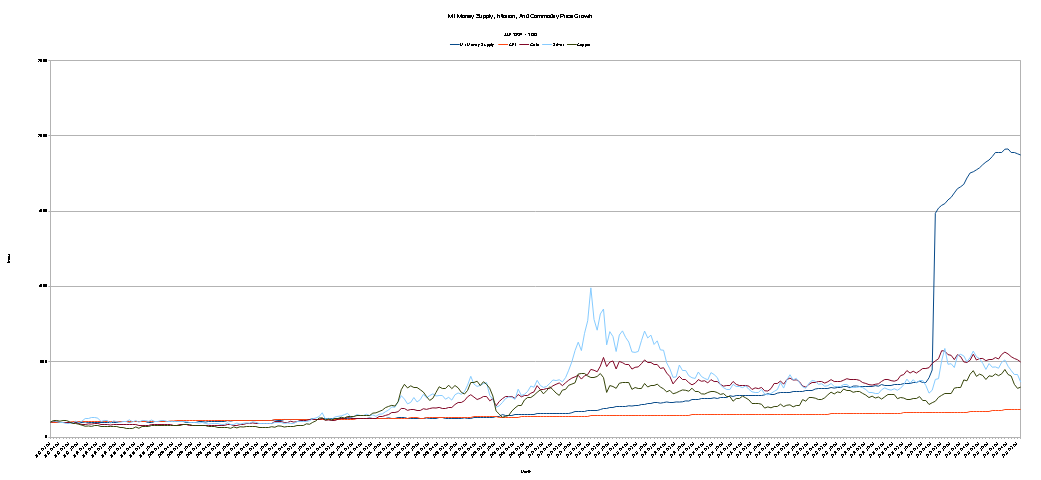

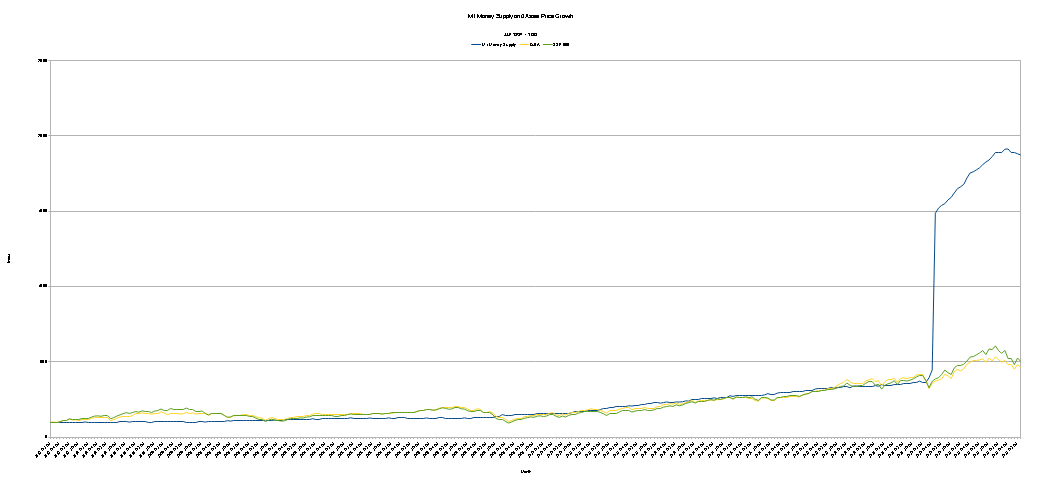

If we overlay an index for the M1 money supply on the same chart, we must immediately question the presumption as well that price inflation for commodities is directly traceable to money supply growth.

Commodity prices fluctuate wildly at all money supply levels, and, most tellingly, we do not see in 2020 an explosion in commodity prices to match the explosion in the M1 money supply when the Federal Reserve injected huge amounts of liquidity into the financial system to stave off potential systemic ruptures and dislocations as the country went through the bizarre and destructive social experiment of shutting the country down.

Not only is there a major distinction to be made between commodity price inflation and consumer price inflation, as the primary forces behind each must be different to produce the measured historical rates of change that we have, but the presumption that commodity price inflation is inherently tied to the money supply—and thus directly amenable to interest rate policy, which acts to shrink or expand money supply as interest rates rise and fall3—is simply not supported by the historical data. Money supply is not irrelevant, but it is foolish to disregard the presence of additional factors and forces which in many instances are more impactful than interest rates and money supply growth.

“Guru” Jeremy Siegel fails to notice this.

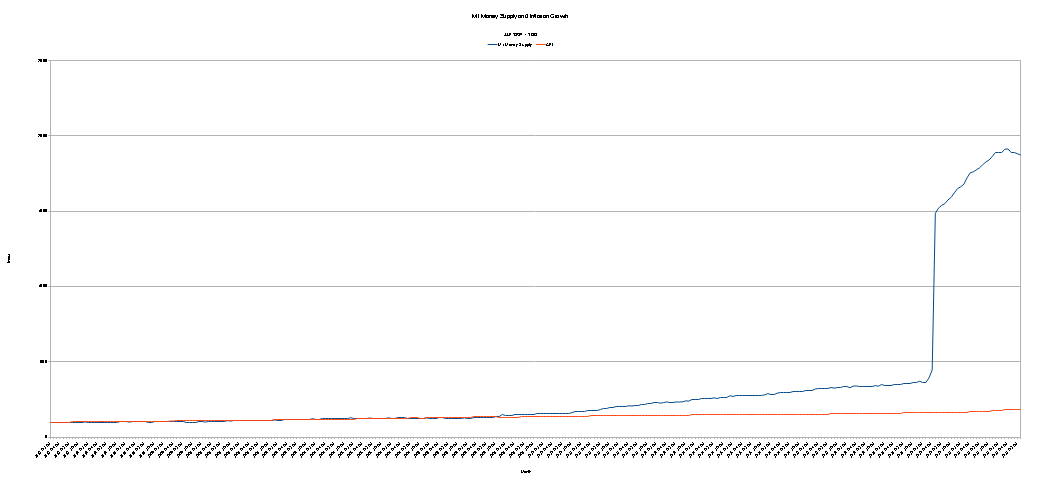

Even Consumer Price Inflation Has Been Divorced From Money Supply Since 2008

Jeremy Sigel also overlooks an important historical shift in the dynamic between consumer price inflation and the M1 money supply: in 2008, the growth in the CPI detached from growth in the M1, whereas historically the two had moved fairly closely together—exactly the behavior we expect to see if we hew strictly to Friedman’s truism that "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon"4.

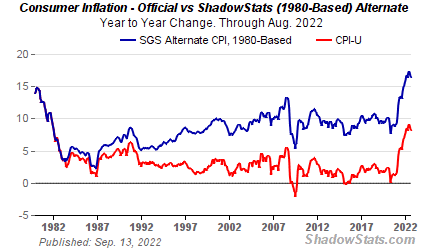

It is this severing of the historic linkage that lies at the core of my criticisms of Fed interest rate policy. Post-2008, it is simply not possible to sustain the Freidmanite premise that all inflation is monetary in nature. The conspicuous lack of a trend shift in consumer price inflation to match money supply growth precludes that option. We should also note that even economist John Williams’ ShadowStats alternate consumer price inflation metrics do not show such a trend shift.

If money supply growth is not the primary driver of consumer price inflation—and the data shows that since 2008 money supply growth cannot possibly be the primary driver of consumer price inflation—attempting to contain consumer price inflation by directly targeting money supply growth is not going to have the same effects in 2022 that it would have had in 2002.

The historical data shows quite plainly that the reflex rationalization of “this time is different” is, for once, actually true. There are differences in the economic landscape today compared to even 20 years ago, let alone to the early 1980s during the Volcker Recession. The extent to which the Volcker playbook can even apply in the present circumstance must be considered problematic.

The Fed’s most grievous policy error with its rate hike strategy is to fail to even notice that this is not the early 1980s. Fighting the last war is a bad enough strategic mistake, but fighting the last war with the last war’s weapons and expecting to win the current war is sheer lunacy.

Siegel, for all his “guru” credentials, is upset Jay Powell didn’t start fighting the last war with the last war’s weapons sooner rather than later, as if such a strategic error would be somehow better made sooner rather than later. Personally, I contend that Powell should be fighting the current war on inflation, and using weapons appropriate to the conflict—although in this case that would mean demanding Congress and the White House address the regulatory and fiscal insanities which have broken supply chains and sent prices skyward.

Asset Prices Started To Trend To Money Supply Starting In 2008

2008 is an intriguing year, economically speaking, because while the consumer price index became unmoored from the M1, asset prices (as measured by the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 stock indices) began to follow the M1 trajectory far more closely than before.

Note that asset price growth from 2008 up through 2019 tracks very closely to the M1 money supply growth, suggesting that the rise in the Dow Jones index as well as the S&P 500 from 2008 onward is more inflationary than real. If this is the case (which I believe it broadly to be), then we begin to see how far asset prices have to fall to get back to “real” valuations.

Looking back to the commodity price growth charts shown above, however, commodities do not follow this same trajectory, and are nowhere near as beholden to money supply growth as asset prices demonstrably have been.

This is the fundamental flaw in Jeremy Siegel’s rant: the primary forces driving consumer price inflation as well as commodity price inflation are, in the present circumstance, non-monetary in nature. This is not to say that money supply growth is not inflationary—pre-2008 data shows quite clearly that it is—but that there is, post-2008, much more to inflation than just the money supply.

The “Experts” Are At Odds With Reality

Looking at the historical data, one thing is absolutely certain: “guru” Jeremy Siegel is arguing a reality that demonstrably does not exist.

Even Ryan McMaken of the Mises Institute does not quite grasp the dichotomy within Fed policy, as he focuses exclusively on monetary inflation (growth in the money supply) in his own jeremiad against Jay Powell without noting the crucial and demonstrable distinctions among monetary inflation, consumer price inflation, and asset price inflation.

Consumer price inflation is a real problem. It erodes individual income and distorts individual consumption, resulting in less consumption and a reduction in overall economic output. In every economy, consumer price inflation is an economic sickness that cannot be ignored.

Yet consumer price inflation is more than a one-dimensional problem. Particularly in the present era, more than just the size of the money supply drives price hikes. Government policies—the lunatic lockdown policies in particular—as well as a seemingly endless series of exogenous supply shocks have conspired to push prices up even as Jay Powell has struggled, through artless and ineffective interest rate hikes, to bring them down.

At some point, even the “experts” must acknowledge this reality. Only at then can Fed policy correct itself into something more economically useful and less economically destructive.

The data used in this analysis comes from the following sources:

M1 Money Supply and Consumer Price Index historical data: The Federal Reserve

Dow Jones Industrial Average and S&P 500 index historical data: Yahoo! Finance

Gold, Silver, and Copper futures historical data: Investing.com

The charts are developed using LibreOffice Calc 7.3.2.2

Indexing to a common baseline date strips out differences in units of measure, allowing for direct comparison of the rates and orders of magnitude of change among disparate data.

Folger, J. What Is the Relationship Between Inflation and Interest Rates? 5 May 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/12/inflation-interest-rate-relationship.asp.

Friedman, M. “Inflation: Causes and Consequences. First Lecture.” Dollars and Deficits, Prentice Hall, 1968, pp. 21–46. Retrieved online from https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/271018/full

To all these charts add an aging population and the velocity of money.

It's a problem for "complexity science." Meaning there may be a useful pattern in it all. But, if AI turns out to be real, then AI might discover it. No human has so far.

PNK, every time I make a deep dive into this data, charts, and such, I feel like what is actually being exposed is that we, the people, are being ripped off big-time, and with 87k more "revenuers" bearing down on us in addition to the others legions of tax collectors, well, it is going to get worse, a lot worse.

Am I wrong?

Another excellent article, thanks!