While no banks have yet collapsed since First Republic Bank was handed to acquired by JPMorgan, there has been no shortage of bad news for the banking sector of late.

By far the grimmest report to emerge yet is the one from the Federal Reserve which showed some 722 banks with unrealized losses in excess of 50% of their capital at the end of the third quarter of 2022.

The U.S. Federal Reserve has revealed in a board presentation by the Division of Supervision and Regulation that 722 banks reported unrealized losses exceeding 50% of their capital at the end of the third quarter of 2022. The presentation, released to the public in April, is dated Feb. 14. It highlights the impact of raising interest rates on certain banks and the Fed’s supervisory approach to address issues at these banks.

The presentation itself is merely a slide deck of crucial talking points, without much of the in-depth explications that such a presentation would normally entail. However, the talking points themselves are fairly disturbing. Even more disturbing is that this presentation is dated February 14—weeks before Silicon Valley Bank was taken over by regulators—providing yet more evidence that banking regulators have been sitting on their hands watching these serial bank and liquidity crises unfold.

Of particular note is the acknowledgment on the “Conclusions” slide that the rising interest rate environment turns otherwise sound securities toxic.

As rates rise, investment portfolios which have traditionally been a source of liquidity will be further limited

This is, readers will recall, a point I have made numerous times in discussing the banking crisis.

Remember, rising interest rates automatically decrease the value of legacy debt security holdings—not only reducing the value of the portfolio (through a ledger entry involving Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (or Loss)), but also making them that much more difficult to sell in order to cover bank deposits.

Across the board, interest rates for the most popular debt securities began rising due to indigenous market forces months before the Federal Reserve issued their first increase to the federal funds rate. As those interest rates went up, the value of bank portfolios of debt securities went down.

By the time the Federal Reserve announced their first rate hike, banks’ securities investments were already well on their way to being underwater.

In keeping with a bureaucrat’s peculiar talent for stating the obvious, the presentation also concluded that the combination of deposit outflows and declining securities valuations is unsustainable.

Higher than anticipated deposit outflows and limited available contingency funding may cause banks to make difficult choices, including reliance on higher-cost wholesale funding or curtailing lending

The irony, of course, is that this sort of liquidity crisis is exactly what numerous commentators including myself have been warning would occur for months.

That the Federal Reserve began to realize this only in February of this year constitutes an epic display of idiocy.

One item the report did clarify which does much to explain why the banks are in a financial straitjacket: in going all in on securities investments they also decided to go long on the maturity—meaning the assets which are now underwater have to be held literally for years before they will roll off bank balance sheets normally.

With some $6 Trillion of securities involved, having that much cash, capital, and liquidity tied up would be a burden for any bank. To avoid unrealized losses the banks have to sit on some $4-$4.5 Trillion in cash for more than three years.

That’s a long time for banks to sit on that much cash and have it be idle.

This report is but one of many reasons the banking sector has been taking it on the chin recently, with the S&P 500 Financials index, the KBW Nasdaq Bank Index, and the KBW Nasdaq Regional Banking Index all ending last week down.

Meanwhile, banks in the US have lost nearly $860 billion in deposits since the beginning of the year.

Even for JPMorgan Chase, that’s a lot of money!

Yet despite the Fed’s own admissions of ineptitude, in some circles there are call for even more regulation of US banks, ignoring the reality that the complexity of the legal and regulatory burdens with which banks must already contend played a role in the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

While the conventional wisdom is that banks simply need to be regulated harder, a report from the Fed’s Board of Governors suggests banks are already struggling to navigate a labyrinth of federal rules and regulations. This was particularly true of SVB, which had experienced rapid growth in recent years, causing it to “move across categories of the Federal Reserve’s regulatory framework.”

That framework, the Fed dryly notes, “is quite complicated” ( indeed ), and the report makes it clear that SVB was spending a lot of time and money on consultants trying to navigate this framework “to understand the rules and when they apply, including the implications of different evaluation criteria, historical and prospective transition periods, cliff effects, and complicated definitions.”

While the ultimate responsibility for SVB’s failure lies with the bank’s management, it does not speak well of banking regulators that SVB was struggling merely to comprehend the regulatory framework being applied to it.

SVBFG’s rapid growth led it to move across categories of the Federal Reserve’s regulatory framework (see the “Federal Reserve Regulation” section). Under the current framework, the application of rules to a particular firm depends on a range of factors related to a firm’s size and complexity. As seen in the visual produced by the Federal Reserve Board, the framework is quite complicated. SVBFG and staff supervising SVBFG spent considerable effort seeking to understand the rules and when they apply, including the implications of different evaluation criteria, historical and prospective transition periods, cliff effects, and complicated definitions. SVBFG regularly engaged consultants to help prepare for the transition

It also does not speak well of banking regulators that, even as they acknowledge the relevance of SVB’s regulatory burden, are seeking even greater regulatory authority over future Silicon Valley Banks.

Moreover, even as banking regulators solve the issues of their own inadequacies by calling for still more regulations, little if anything is being said about the reality that the US banking system’s “large” banks have suffered by far the greater degree of deposit outflow, both in absolute and relative terms.

That the banks most at risk from deposit outflows are the larger rather than the smaller banks is something that is still going largely ignored within the banking sector.

Issues of bank size aside, and even as banks continue to struggle to regain their footing on Wall Street, the banking sector appears woefully oblivious to the acknowledged systemic risks swirling around commercial real estate.

Office occupancy rates suck. Prior to the COVID pandemic, office occupancy rates in the United States were hovering around 95% nationwide. Today, office occupancy rates are approximately half that. In the haste to “flatten the curve” as evangelized by the Pandemic Panic Narrative, companies large and small embraced a standard of “work from home” for many of their office staffs. Company meetings were replaced by Zoom videoconferencing, and company offices became ghost towns.

Before the pandemic, 95% of offices were occupied. Today that number is closer to 47%. Employees' not returning to downtown offices has had a domino effect: Less foot traffic, less public-transit use, and more shuttered businesses have caused many downtowns to feel more like ghost towns. Even 2 1/2 years later, most city downtowns aren't back to where they were prepandemic.

While the Pandemic Panic Narrative has collapsed and largely faded from sight (thankfully!), office workers have been reluctant to return to the office. A home office is apparently much more comfortable than a cubicle (shocking!), and workers have responded to calls by corporate management to return to the office with a general shrug and the question “why?” The result has been a drastic increase in vacant offices and vacant office buildings.

So dire is the situation, according to some, that as much as 65% of existing office space is surplus and simply not needed.

Boston Consulting Group estimated that 60% to 65% of current U.S. office space will not be needed. “That means about 1.5 billion square feet of office space could become obsolete, which would translate into $40 billion to $60 billion of lost revenue for building owners,” the report said.

Yet despite such grim prognostication, many real estate assets themselves have actually gained in the aftermath of SVB’s failure. A quick survey of indices for various Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) classes shows virtually all have gained in market since SVB’s collapse.

Apparently no one informed REIT investors that theirs was a risky investment.

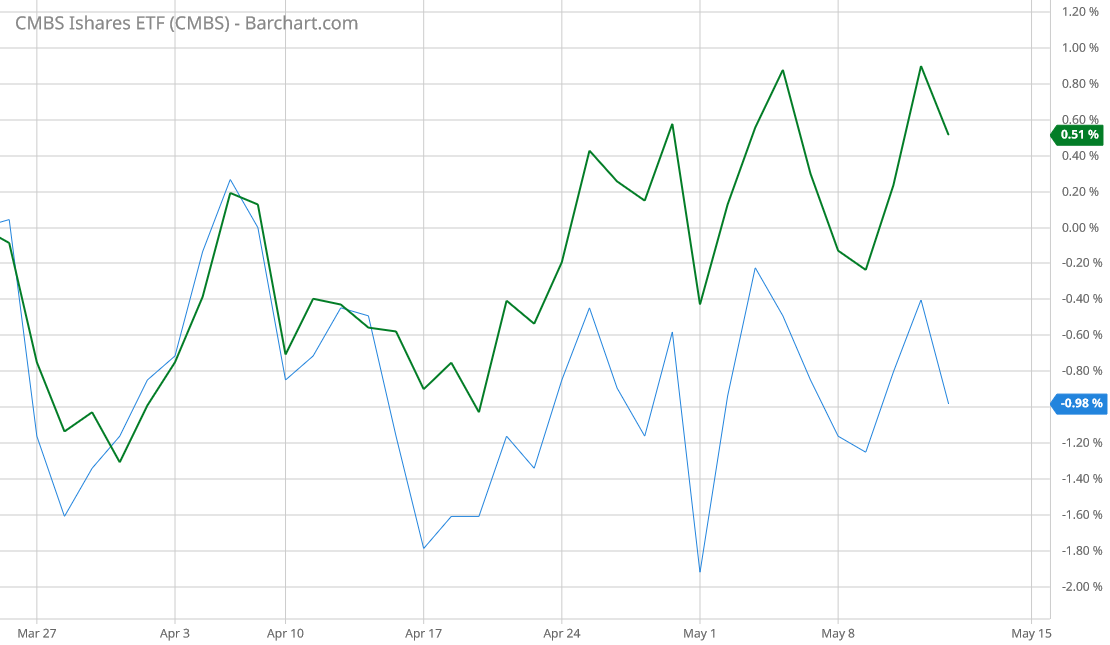

Nor is it merely REITs. ETFs for Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities have since March outperformed their residential mortgage counterparts.

While banks went to some length to trim their exposure to underwater commercial real estate loans in the wake of SVB’s collapse, by last week nearly all of the shed loan assets had been replaced.

If commercial real estate is going to be catalyst for the next phase of the banking crisis, banks certainly do not seem to be doing much to avoid the risk.

There is, of course, a more cynical view: banks know exactly the risks they are taking, but remain convinced that the government will yet again ride to their rescue, bailing out failed banks much the way the financial sector was bailed out in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis in 2007-2009.

CEO and portfolio manager for Pershing Square Capital Bill Ackman has been expounding at some length over the need for the FDIC and the Fed to “save” regional banks, ideally by preemptively extending FDIC coverage to all bank deposits regardless of size (currently the FDIC only insures deposits up to $250,000).

Ackman explained that the “failure” of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) “to update and expand its insurance regime has hammered more nails in the coffin.” He stressed that First Republic Bank “would not have failed if the FDIC temporarily guaranteed deposits while a new guarantee regime were created. Instead, we watch the dominoes fall at great systemic and economic cost.” First Republic Bank was seized by regulators earlier this week and most of its assets were sold to JPMorgan Chase.

Ackman’s solution is more bailout money and more moral hazard.

“How many more unnecessary bank failures do we need to watch before the FDIC, U.S. Treasury, and our government wake up? We need a systemwide deposit guarantee regime now,” he concluded.

The US has a “systemwide” deposit guarantee regime already—one that is limited to the first $250,000 of deposits. Yet despite the obvious risks not only have banks been scooping up uninsured deposits the past few years, they have been plowing those deposits into low-yield investments with long maturities, securities which are now underwater and which cannot easily be sold off without catalyzing the recognition of billions of currently unrealized losses.

Despite the bank failures that have happened, despite the known and widely covered headwinds confronting commercial real estate, banks are still growing their commercial loan books. REITs are still appreciating in value. Commercial mortgage backed securities are increasing their market value of late. Everything that the corporate media has been saying is now toxic because of rising interest rates has appreciated in value since SVB’s collapse.

Could it be that bankers are gambling yet again on another industrywide bailout? Are they anticipating that Cassandras such as Bill Ackman will be heard only at the eleventh hour, at which point the government will be “forced” to step in with a dramatic bank rescue effort?

That would be the cynical read of the existing data—and yet one has to wonder. The Fed and the FDIC have known for months that banks (including Silicon Valley Bank) are becoming increasingly overextended and vulnerable to a liquidity shock, yet by their own documentation they simply sat back and let the banking crisis unfold.

Bankers were told last year that their risk management was off-target, yet they simply sat back and let their banks hurtle headlong into oblivion.

Despite three historic bank failures in less than two months, both regulators and bankers alike are blindly and blithely going through the same motions, continuing to make the same seeming mistakes, apparently doing little if anything to mitigate any of their risks.

Bankers, it seems, are waiting for regulators to bail them out. Regulators, it seems, are waiting for bankers to acknowledge the need for them to bail themselves out.

Which side is bluffing? Which side has the stones to call the other’s bluff?

Somehow, I don’t think the answer to either question is going to be at all reassuring.

Community banks ($1 B or less) typically do not have these problems. (Of course, they are also not run by “the smartest people in the room.”). If the big or so-called “small” banks do not destroy the entire banking system,it would be nice to see a predominantly community bank system emerge from this mess.

It really feels, that as with any area of our American economy and government, nobody knows anything. Banks are certainly betting on a government bailout, and everyone else is putting their heads in the sand. It will be an interesting time to see where this all ends.