The benchmark price of Brent Crude got a shot in the arm last week after the International Energy Agency revised its forecast of global supply and global demand, moving its estimates more in line with OPEC’s own forecasts.

Crude oil prices hit a four-month high on Thursday, with the U.S. benchmark crossing over the $80 mark and Brent passing $85 per barrel after changes in supply and demand predictions that bring OPEC+ and International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts into closer alignment.

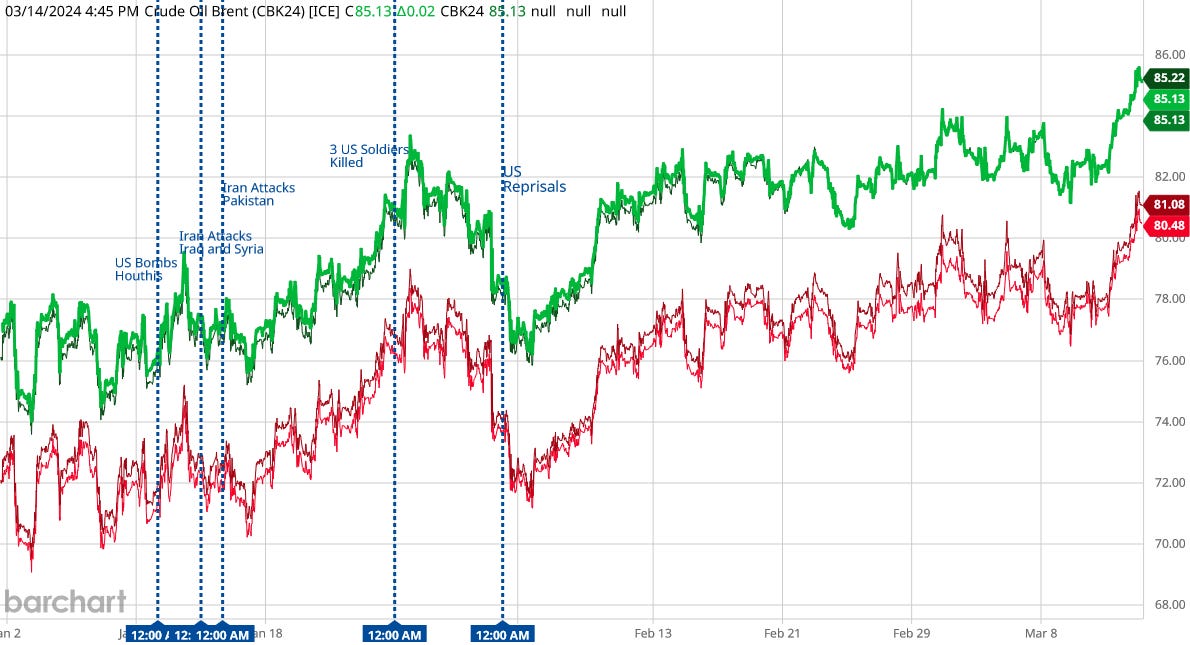

After gaining nearly $3 on Wednesday, at 3:43 p.m. ET on Thursday, Brent crude was trading at $85.23, up 1.43% on the day. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) was trading at $81.13, up 1.77% on the day.

Earlier on Thursday, the IEA tweaked its forecasts for this year, predicting a tighter market and higher demand growth than previously anticipated, primarily due to disruption from Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping lanes.

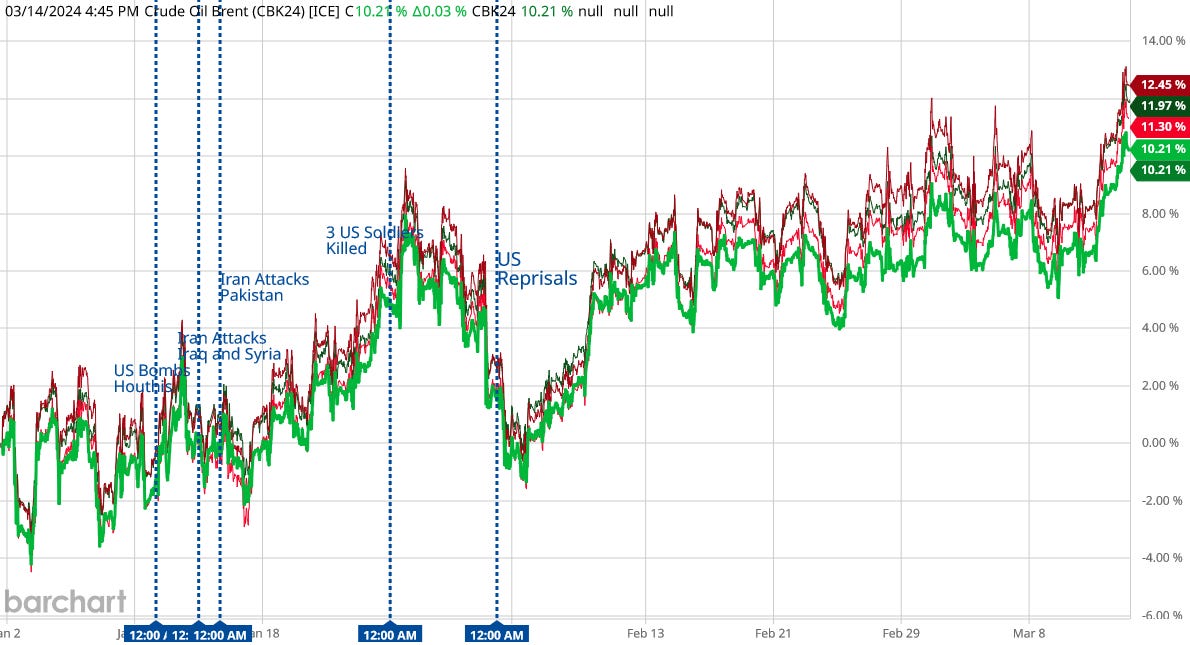

Thursday’s price movements were one of the largest single-day price increases for Brent Crude this year, and marked Brent breaking above a trading band that had been established mid-February.

As is the normal price trend, West Texas Intermediate crude also surged, keeping its usual $3-4/bbl price differential to Brent.

Since the first of the year, both Brent and West Texas Intermediate have risen approximately $9/bbl—roughly 10-12%—the largest such increase since the price rises last summer when the OPEC production cuts began to bite.

Throughout 2023 the media narratives were replete with forecasts of “$100/bbl oil” that never materialized. Has the market finally turned?

Oil market analysts and experts will always have their forecasts and opinions about future oil price movements, but let us see what the historical data can tell us.

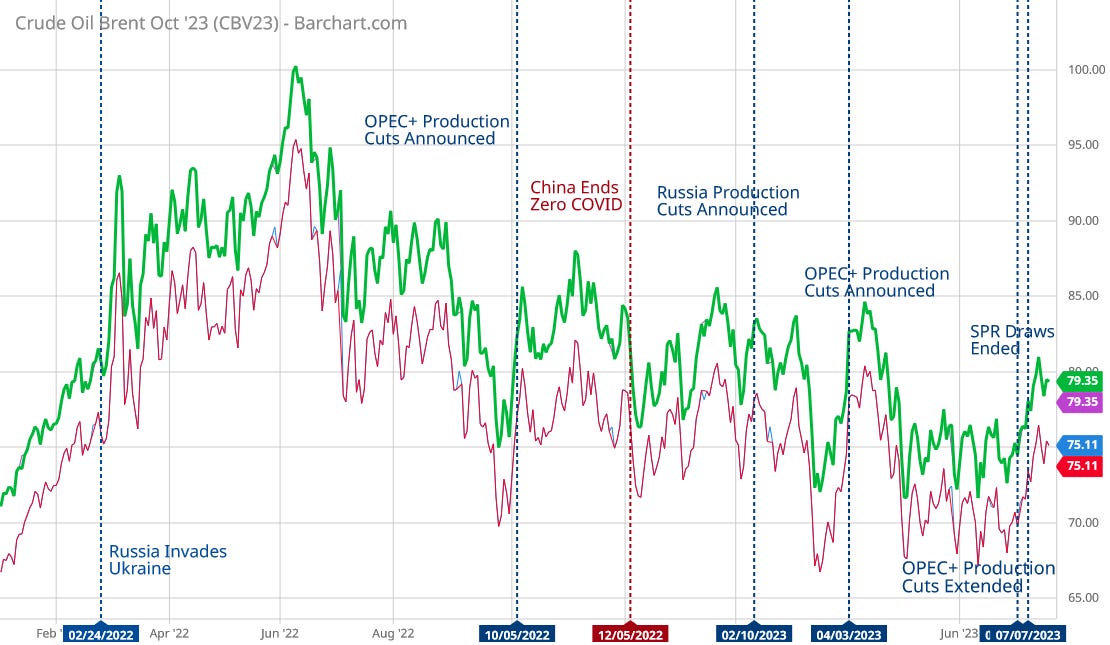

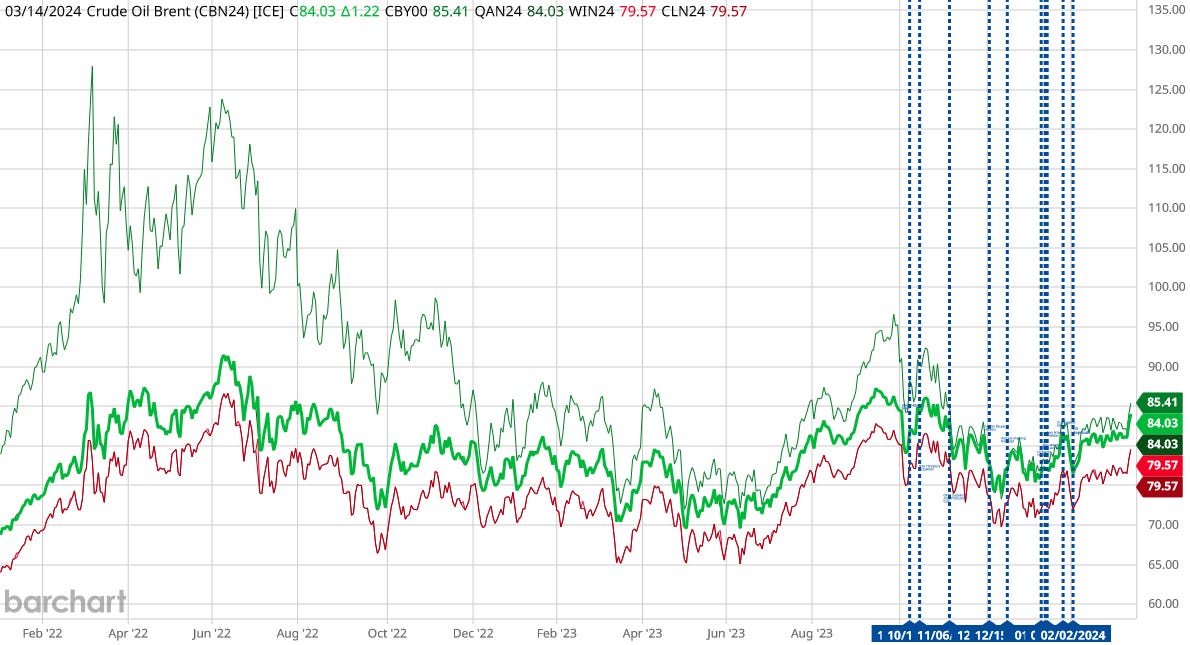

Understanding the trends in energy prices was, readers may recall, something of a challenge last year. After some extreme volatility in the spot price for Brent Crude in 2022, largely as a result of the war in Ukraine, 2023 began with a bit less volatility in spot prices and mostly a downward trend in crude oil prices overall.

Throughout the spring of 2023, the data indicated that oil demand relative to oil supply was steadily shrinking, with the result that oil prices continued to drop even with production from Saudi Arabia and Russia being curtailed.

Yet even this year’s trading bands for oil amount to little more than a more gradual decline in oil prices from last summer’s peak.

Given the softness that had been self evident from late 2022 through mid 2023, at the time it seemed unlikely that the June prices would represent any sort of price floor for oil, and that had been my assessment at the time.

However, the trading bands we have seen this year, both of which were largely established after OPEC production cuts were announced, have seen their upper bound broken only to have the new trading equilibrium established at a lower price than before. That indicate that oil demand is not merely soft but is itself shrinking.

The world is not demanding more and more oil, at the moment, but progressively less less and less. That has been the macro trend since October of last year.

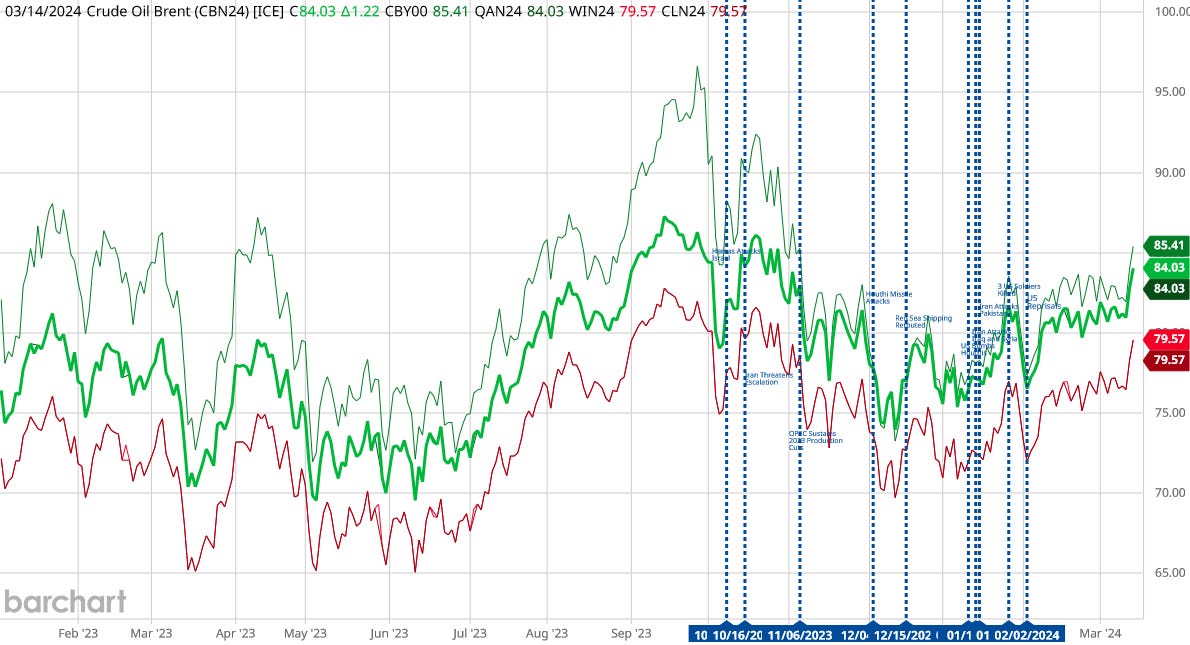

As subsequent data would reveal, that assessment was wrong. June 2023 has very much been the price floor for oil. Indeed, by the end of June oil prices were climbing, and would continue to climb through August and September, with spot Brent prices climbing even farther. With the war in Ukraine having settled down into a stalemate in eastern Ukraine, and the Israeli-Hamas War yet to begin, the Russian and Saudi production cuts had finally succeeded in pushing oil prices up for a time.

The production cuts are pushing up oil prices. That much is fairly certain. Everything else remains uncertain. Whether oil demand in the second half of the year will rise as forecast even with significantly higher prices remains very much to be seen. With China slipping into deflation and the US not far behind, forecasting increased oil demand going forward could prove to be mostly wishful thinking.

Saudi Arabia and Russia have gotten their wish: they have successfully pushed up oil prices. However, the price of being able to do so is restraint on how much oil they can sell. That may end up making the production cuts more expensive to Russia and Saudi Arabia than they are worth.

Despite the upward trend, my take on oil prices was that they would stabilize, and then begin to move downward again.

Oil prices may show some additional increases over the near term, but oil prices are still likely to stabilize within a particular price range over that same near term. After they stabilize, the steadily deteriorating global economy will once again begin to pull oil prices back down again.

The following week, oil prices reversed and began moving sharply lower.

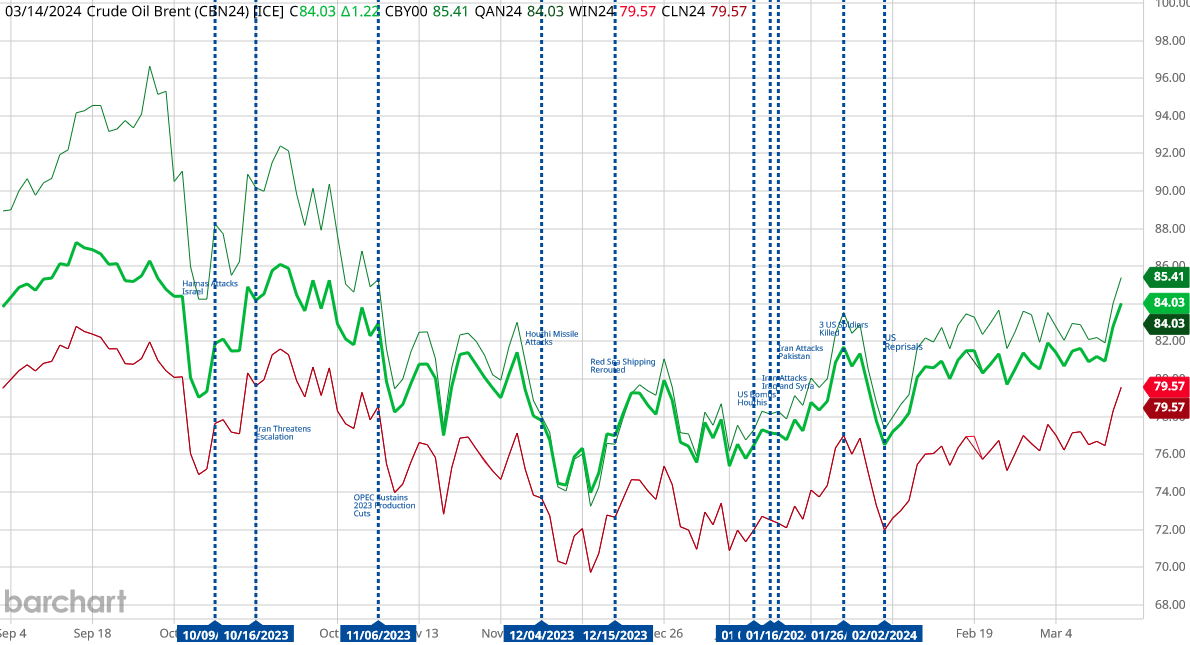

Intriguingly, Hamas’ surprise attack on Israel on October 7 did not produce an extended surge in oil prices. Quite the opposite, as oil prices continued to move lower in spite of the rising tensions in the Middle East. War in Gaza, Houthi missile attacks in the Red Sea, and assorted other mischief by Iranian proxy militia groups, and still oil prices did not reverse higher.

It would not be until the Houthi missile attacks in the Red Sea began to take a toll on a major global trade route that oil prices would find a floor once more.

Yet even with that, until last Thursday, oil prices settled into a relatively narrow trading band by early February. This despite US reprisal strikes against the Houthis as well as other Iranian proxies in Iraq and Syria, especially after three US servicemen were killed in Jordan.

War and rumors of war were not enough to push oil prices higher at that time.

What changed on Thursday?

Primarily the change is a revised oil demand forecast by the International Energy Agency, bringing demand and supply forecasts more in line with OPEC’s own forecast.

Crude oil prices hit a four-month high on Thursday, with the U.S. benchmark crossing over the $80 mark and Brent passing $85 per barrel after changes in supply and demand predictions that bring OPEC+ and International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts into closer alignment.

After gaining nearly $3 on Wednesday, at 3:43 p.m. ET on Thursday, Brent crude was trading at $85.23, up 1.43% on the day. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) was trading at $81.13, up 1.77% on the day.

Earlier on Thursday, the IEA tweaked its forecasts for this year, predicting a tighter market and higher demand growth than previously anticipated, primarily due to disruption from Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping lanes

Whether oil demand will hold up as the IEA and OPEC now anticipate remains to be seen. However, there is little denying that the Houthis are succeeding in disrupting maritime traffic through the Red Sea, as their missile attacks continue despite US air strikes against the missile sites themselves.

Because of the Houthi menace in the Red Sea as well as OPEC’s likely decision to extend its production cuts throughout 2024, the IEA forecast is for substantially less oil flowing to the global market.

Global oil demand is forecast to rise by a higher-than-expected 1.7 mb/d in 1Q24 on an improved outlook for the United States and increased bunkering. While 2024 growth has been revised up by 110 kb/d from last month’s Report, the pace of expansion is on track to slow from 2.3 mb/d in 2023 to 1.3 mb/d, as demand growth returns to its historical trend while efficiency gains and EVs reduce use.

World oil production is projected to fall by 870 kb/d in 1Q24 vs 4Q23 due to heavy weather-related shut-ins and new curbs from the OPEC+ bloc. From the second quarter, non-OPEC+ is set to dominate gains after some OPEC+ members announced they would extend extra voluntary cuts to support market stability. Global supply for 2024 is forecast to increase 800 kb/d to 102.9 mb/d, including a downward adjustment to OPEC+ output.

It was the latter shift that oil analysts attribute Thursday’s jump in benchmark oil prices.

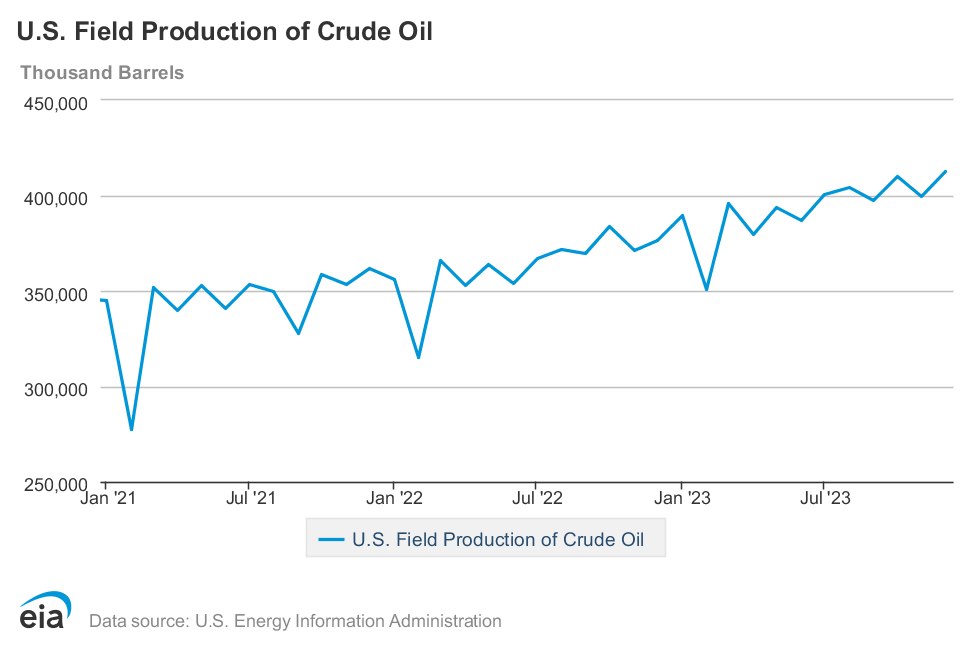

It is worth noting that, despite various disruptions to global oil supply, from Russia sanctions to OPEC production cuts to Houthi missiles, one trend that has been consistent since 2021 has been rising oil production here in the US.

One reason events in the Middle East have not had a greater impact on global oil prices is that the US has been stepping in with greater oil production to mitigate any supply disruptions. So successful has US oil production been over the past few years that the US has effectively weaned itself off foreign oil, and has been a net oil exporter.

In a report published on March 5, Michael Cembalest, chair of the bank's market and investment strategy arm, declared that "the U.S. has achieved energy independence for the first time in 40 years while Europe and China compete for global energy resources."

An accompanying statistical review of fossil fuel movements suggests that the U.S. was a net importer of fossil fuels throughout the 1980s to the 1990s, reaching a peak in the late 2000s before imports steadily declined relative to exports. It became a net exporter around 2019, and as of around 2022 was providing nearly 200 million tonnes of fossil fuels to the global market.

Energy independence means America is less likely to suffer from shortages of fossil fuels and price rises due to fluctuations in international markets.

However, we should also note that there is a potentially major flaw in both OPEC and IEA oil demand forecasts: neither Europe nor China are exactly engines of economic growth at the moment.

Europe is, as I noted last week, slowly but surely de-industrializing.

Unlike China’s economy, which has entered into a deflationary death spiral, and unlike the United States, where things are merely stagnating for the most part, the European economy is simply coming to a halt. Broadly across the European economy, everything is slowing down, shrinking, and eventually stopping.

Unless Europe can reverse that trend and restart its manufacturing base, there is a point some years out—perhaps a decade or more in the future—where Europe will simply cease to be a leading economy. Unless Europe can re-energize its economy soon, we will be looking at the eventual cessation of the European Union as an economic entity at the very least, and possibly as a political entity as well.

China is saddled with a seemingly endless series of economic challenges, the most dire of which is their ongoing real estate crisis, which has now begun to threaten even the “safe” state-owned developers.

No matter how China Vanke’s debt crisis resolves—as a state-owned enterprise it is unlikely Vanke will be forced into bankruptcy—that the crisis is happening at all is the strongest signal yet that China’s economy is not merely slowing, but is quite literally falling apart.

There is no talk of “soft landings” for China’s economy. China Vanke proves that none are even remotely possible. That landing is going to be hard, is going to be painful, and is going to do lasting damage.

Even before that latest evolution in China’s collapsing property bubble, it has been apparent that China has been sliding into deflation, which means their economy is contracting and not expanding.

With the US at the moment largely energy independent, and with China and Europe flirting with recession, potentially depression, as well as de-industrialization (at least for Europe), predictions of large increases in global oil demand would seem to be overly optimistic.

Certainly when we look at oil prices going back to the start of 2022, before the war in Ukraine began, we see that oil prices now are largely where they were then.

Volatility in spot oil prices aside, the overall trend in oil prices since the start of 2022 has been, amazingly enough, largely horizontal. Brent prices now are still below where they surged in the opening days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and they are well below where oil prices peaked in June of 2022 before reversing.

Oil prices have been climbing over the short term, and those price rises have been sufficient to, among other things, reignite factory gate inflation in the US.

However, at present Brent crude has yet to surpass even the secondary peak reached in September of last year, and is well below the June 2022 peak when the futures price for Brent reached $91/bbl. When oil prices reached either peak, what followed was an extended price decline.

If that pattern holds, then oil prices may not have much farther to rise before reversing and trending down once again. If the price of Brent climbs past $86/bbl, then the obvious tightness in global oil supply could push oil prices much higher.

If that pattern holds, then very likely within the next week or so oil prices will begin trending downward once more—with no clear indication how far those prices will fall before stabilizing.

If that pattern does not hold, the world might be grappling with major price increases in oil, despite the collapsing economies of Europe and China.

Whether the pattern does or does not hold, 2024 is certain to be “interesting times” for energy prices!

Peter, when agencies such as the IEA issue their forecasts, do they base them on the ‘official’ growth forecasts given by countries, or do the mineral economists involved use their own judgement on what the real-world growth will be? I’m specifically thinking of China here. What the CCP announces to the world regarding China’s expected growth and what we are likely to see in China this year may end up being drastically different. The experts at the IEA and OPEC surely must know this (to some degree), and I’m wondering if they use some sort of ‘bullfeathers weighting factor’ to get figures closer to economic reality.