New York Magazine’s “Intelligencer” column had chosen recently to weigh in on consumers’ apprehensions regarding inflation and interest rates—and managed to largely omit intelligence from the discussion.

The entire article is a study in un-self-aware irony, which the closing paragraph—in still further irony—captures quite succinctly.

All of which is to say, voters’ disapproval of Biden’s economic management is plausibly rooted in objective conditions. But that isn’t necessarily bad news for the president. If inflation continues to moderate, then the Federal Reserve may cut interest rates next year, alleviating some of the pressure on consumers. At the same time, with each passing day, the post-COVID inflationary surge recedes further into the past. If the U.S. economy can continue on its current trajectory through Election Day, then voters may be more forgiving of Biden in November 2024 than they are today.

In other words, the “experts” within the corporate media elites acknowledge that inflation is a problem for most people, but that’s okay, because the Federal Reserve will rescue them the same way they “rescued” the economy from COVID (don’t slip on the dripping sarcasm), and it’s going to be okay anyway because it’s all in the past so let’s just move on and continue to vote Democrat, okay?

I am reminded at this point of Ronald Reagan’s immortal quip from his 1980 Presidential campaign:

“The most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the government and I'm here to help.”

Dementia Joe, his authoritarian regime and its execrable Reign of Error, the malign incompetence of the Federal Reserve, as well as the deluded propaganda of the corporate media have not helped people. Quite the contrary, government choices and corporate media apologetics have served to make ordinary people’s lives far worse post-COVID than they were pre-COVID.

In or out of government, to borrow again from Reagan, the “experts” have not been any sort of solution; they have been the problem, and continue to be the problem.

First, we should note that this sort of self-congratulatory cluelessness is part and parcel for the “Intelligencer” column, which previously concluded that the poor beknighted befuddled voters in this country just didn’t understand how wonderful the current regime has been and were just plain wrong about the state of their own lives.

Many Democrats have found this state of affairs perplexing. Last week, I argued that the public’s hostility to Biden in general, and his economic stewardship in particular, was misguided but comprehensible. After all, real wages and real personal disposable income have both declined during the president’s time in office. The pandemic reduced the global economy’s productive capacity by disrupting supply chains, abruptly shifting consumer spending patterns, and severing ties between workers and employers. We could have paid for this damage through a sustained period of elevated unemployment. Instead we paid for it with a decline in real wages. This was the better option on the merits. So even though the Biden economy looks very good, it wasn’t hard to understand why many voters would be displeased by the fact that they cannot afford as high of a living standard now as they did before the pandemic.

Since writing that column, I’ve learned that one of my key assumptions was faulty. Although the average real hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory workers has declined since Biden took office, that drop likely derives in part, if not in full, from changes in the composition of the labor force.

Note the points conceded here: real wages and real personal disposable income have declined during Dementia Joe’s Reign of Error, but that’s a good thing because the alternative was a sustained period of “elevated unemployment”. Screwing everyone a little is vastly superior, or so we are told, than screwing some people alot.

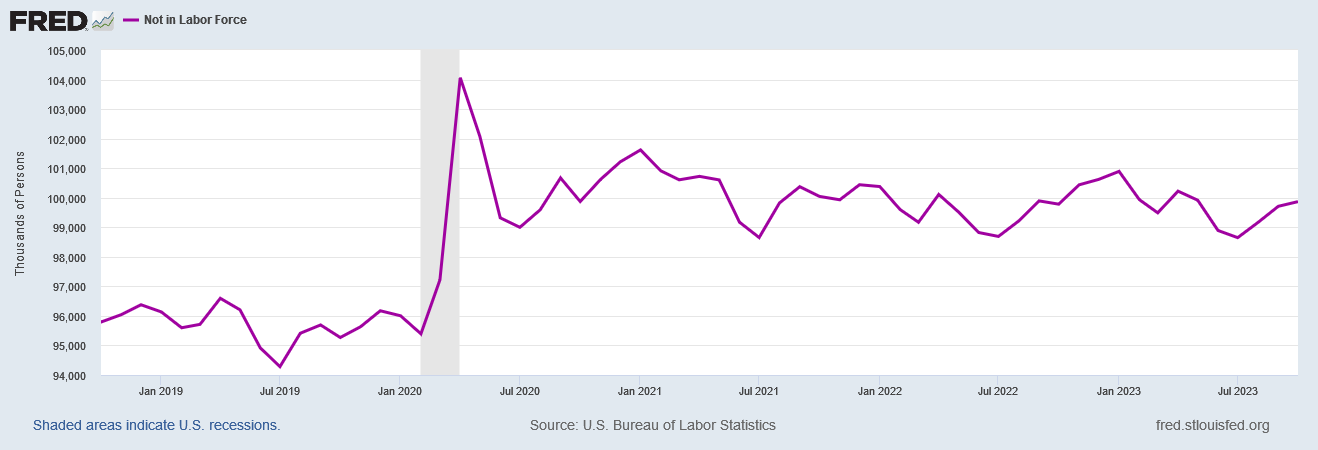

However, some people have been screwed a lot, and some people continue to be screwed a lot. Pointing to the low unemployment rate reported by the BLS each month ignores the arguably more important metric of people not currently in the labor force, which rose tremendously during the Pandemic Panic Recession and remains elevated well above pre-pandemic levels even today.

Roughly half of the workers forcibly displaced during that arbitrary and artificial recession to this day remain on the sidelines. People forcibly ejected from the labor force (and, obviously, their jobs) are just as unemployed as those those recently separated from a job and still looking for work.

4.48 million workers still left excluded from the labor force is by definition a period of “sustained elevated unemployment”. The very thing the Intelligencer column suggests was avoided is the very thing the Federal Reserve insisted happen.

We should not forget Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin’s casual dismissal of displaced workers during the summer of 2022 within his view of how to corral accelerating consumer price inflation (emphasis mine).

Barring an unanticipated event, I see rising rates stabilizing any drift in inflation expectations and in so doing, increasing real interest rates and quieting demand. Companies will slow down their hiring. Revenge spending will settle. Savings will be held a little tighter. At the same time, supply chains will ease; you have to believe chips will get back into cars at some point. That means inflation should come down over time — but it will take time.

Tom Barkin wanted less employment in this country, believing that would bring down inflation—yet the Intelligencer suggests that Tom Barkin did not get his wish.

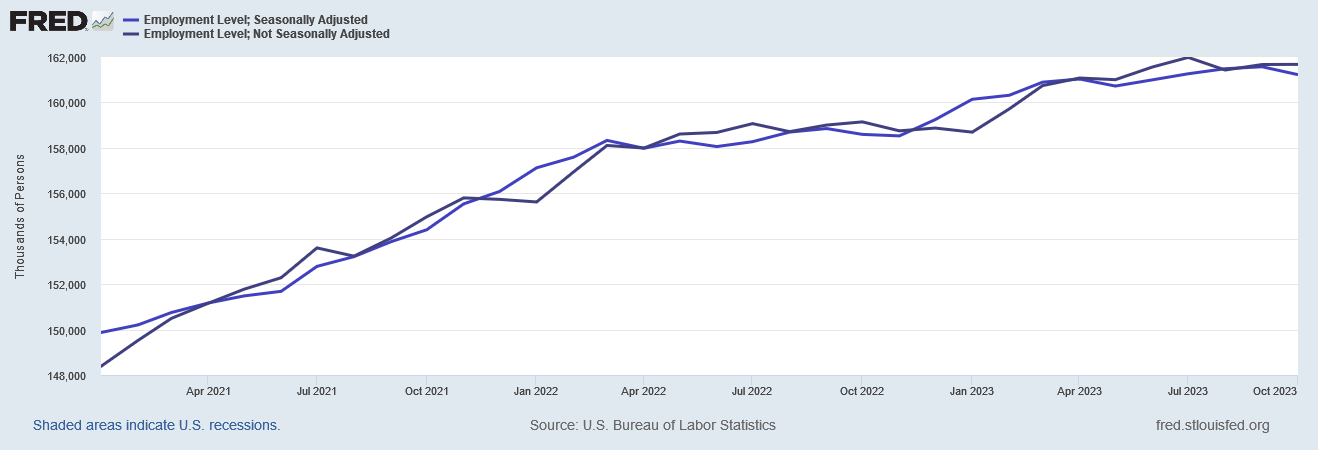

One need only look at the plateau that occurred in the employment level for this country during 2022 (in both the unadjusted and seasonally adjusted metrics) as well as recent declines in the employment level (again, in both the unadjusted and seasonally adjusted metrics) to see just how wrong the Intelligencer is on this point.

Remember, the Federal Reserve itself concluded late last year that, while the Bureau of Labor Statistics claimed that 1.19 million jobs were created during the second quarter of 2022, in reality only 10,500 jobs were created.

The April Employment Situation Summary claimed 428,000 jobs were added that month.

The May Employment Situation Summary claimed 390,000 jobs were created during the month.

The June Employment Situation Summary claimed 372,000 jobs were created during the month.

All told, the Bureau of Labor Statistics claimed 1,190,000 jobs were created during those three months.

Last week, the Philadelphia Federal Reserve shredded the narrative, stating that the actual number of jobs created during those three months was a whopping 10,500.

The Intelligencer also engages in shameless spin when discussing the state of real wages in this country, claiming that real wages have been rising in 2023 and things are better than before the pandemic.

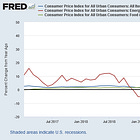

From one angle, the electorate’s antipathy for Biden’s economy doesn’t look all that hard to understand: Although real wages have been rising since February, the first two years of Biden’s presidency witnessed an exceptionally prolonged period in which consumer prices outpaced paycheck growth. In other words, for most of the Biden-era, U.S. workers’ purchasing power was falling.

Graphic: Statista

Again, this reversed in 2023. And the real hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory workers in the U.S. is now higher than it was before the pandemic.

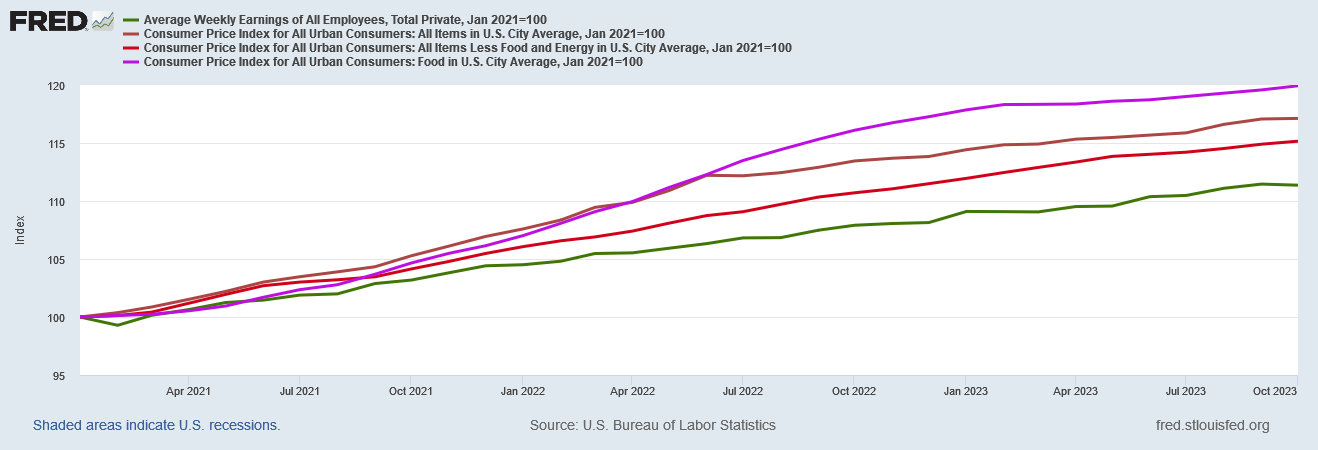

This is one of those “technically true” but substantively irrelevant factoids. This perspective overlooks the cumulative impact of wage and price increases—a point I have raised multiple times when discussing employment in this country.

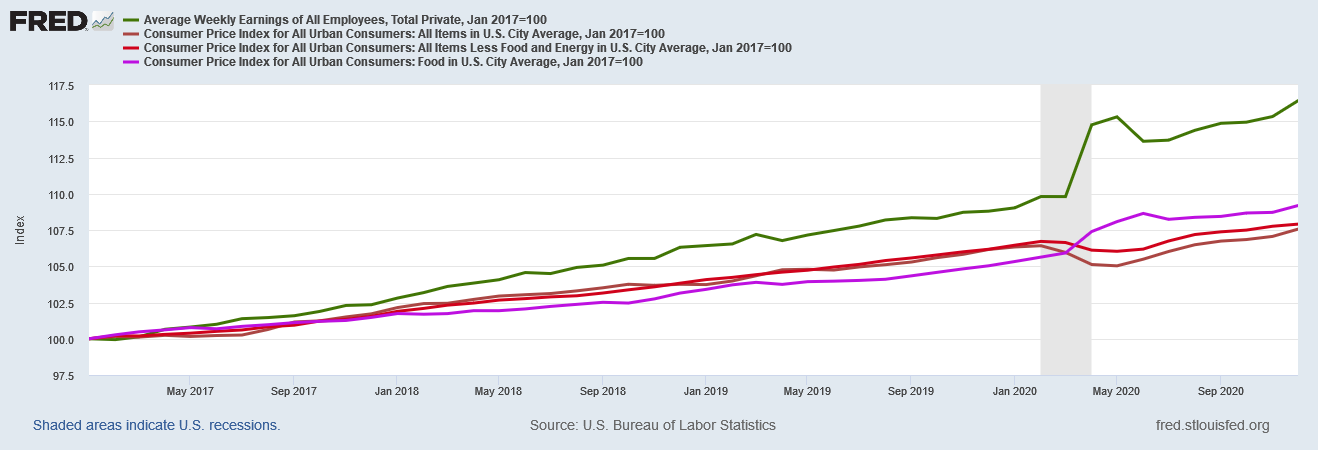

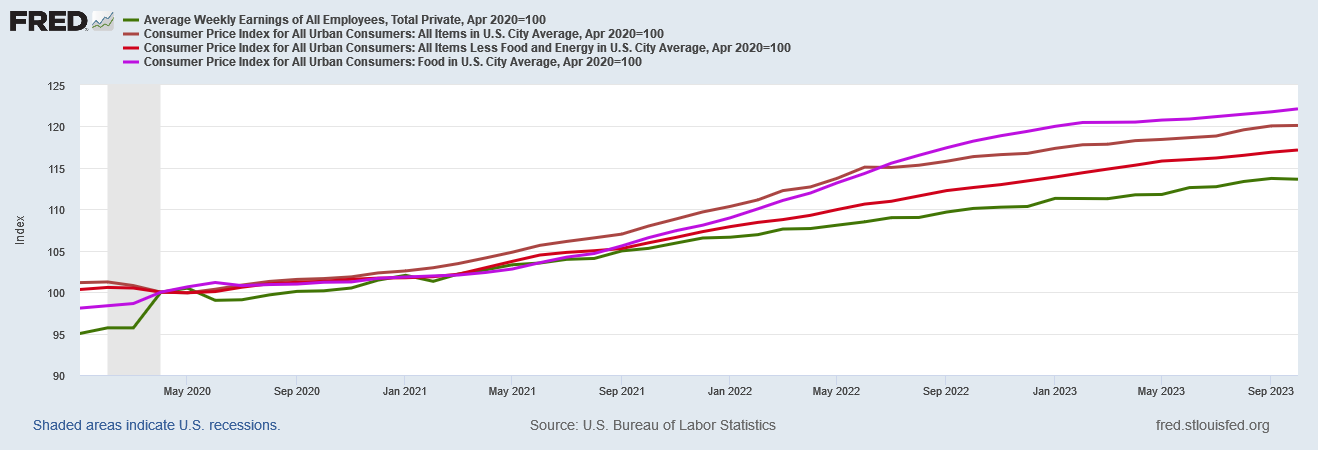

The reality is that wage growth has not even remotely kept pace with consumer prices, and especially important consumer prices for things such as food, since January of 2021.

Wage growth from January 2021 to October 2023 has been roughly half that of food price inflation for the same period. Core and headline consumer price inflation have both grown by several percentage points more than wages during that time.

Talking about recent “real wage” increases while ignoring the extent to which cumulative wage increases have fallen short of inflation is nothing short of delusional propaganda. Real paychecks are smaller now than when Dementia Joe entered the Oval Office, and no statistical spin-doctoring can change that.

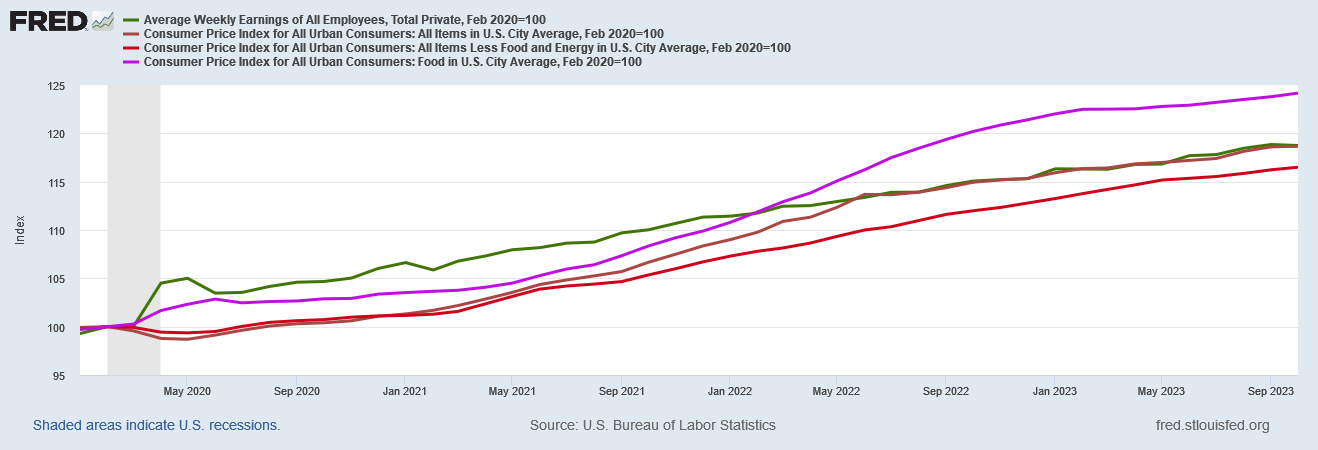

In fact, the only reason that the statistics show real wages to be higher now than before the pandemic is because of real wage growth that occurred during President Trump’s final year in office.

The story of real wage growth in the United States is a credit to Donald Trump’s term of office, not Dementia Joe’s.

Even at that, virtually all such wage growth occurred during and immediately after the Pandemic Panic Recession, with workers losing ground ever since.

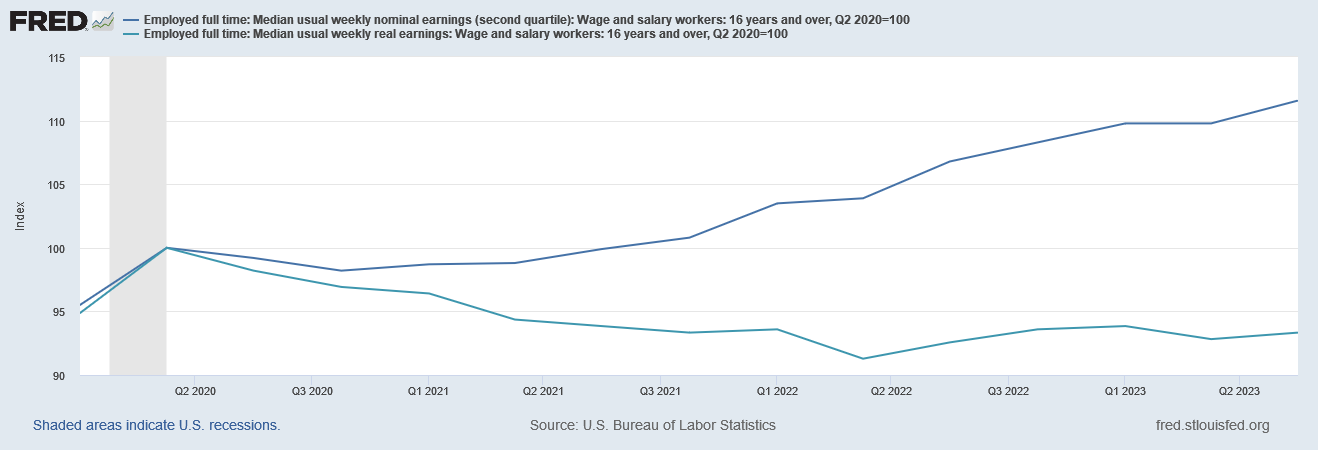

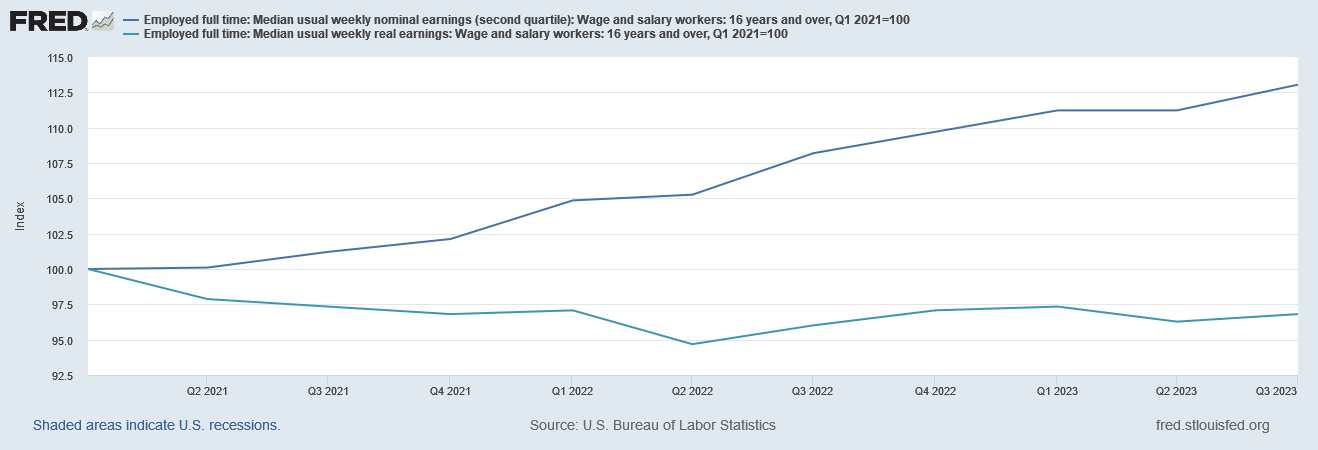

Even if one accepts the “official” calculations of real wages, the reality of real wage growth in this country is that there has not been any real wage growth since the Pandemic Panic Recession, as a comparison of real and nominal median wages since then illustrates.

Focusing on just Dementia Joe’s Reign of Error does not make the real wage picture look any better.

Yet we should not exclude the Federal Reserve from either scorn or criticism. While the Federal Reserve has touted interest rate hikes and tighter monetary policy as the key tools for containing rampant consumer price inflation, research by the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives (CMFA) echoes something I have been arguing in this Substack for well over a year now: The Fed’s policies have not impacted inflation hardly at all, with external factors playing a far more relevant role in consumer price inflation’s decline since June of 2022.

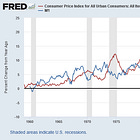

While even a VAR analysis has its limitations, as our new Cato working paper demonstrates, the Fed has not exercised significant control over inflation. Specifically, the paper uses a VAR framework to study changes to the Fed’s preferred measure of prices, the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) index (and its components), for various periods from 1960 to 2019.

The paper shows that in response to unanticipated tightening to the policy rate, a so‐called positive “monetary policy shock,” inflation often increases. This change, of course, is in the opposite direction the Fed is trying to achieve. Put differently, in response to the Fed’s tightening, inflation rarely falls and when it does, it falls minimally.

What the research1 argues, in other words, is that the Federal Reserve has made things demonstrably worse, not better.

The empirical evidence does not support these assertions. This paper investigates the effects of unanticipated changes to monetary policy on inflation and finds that the public perception of the Fed’s ability to manage inflation is overstated. Using standard monetary Vector Auto Regressions (VARs) that are fitted to various data samples from modern U.S. economic history, we show that as a result of a one standard deviation (positive) shock to the Fed’s policy rate, inflation initially increases and only reduces after a few quarters. Not only does inflation initially move in the opposite direction the Fed would want, but the future reduction is small, with the most impact in the services sector. The goods market is the most responsive to the policy rate shock, but the effects are not as intended; in response to the policy rate change, goods prices elevate in the short term and return to normal but never reduce. In short, the desired effect (a reduction in inflation after raising the policy rate) is very small and occurs only in the services sector, but the undesired effect (an increase in inflation) happens to a greater degree on the goods market.

Additionally, our results suggest that monetary policy explains only a small fraction of the variability in inflation at all horizons studied (3-months to 5-years). The share of monetary policy shocks in determining inflation variability rarely exceeds 10% and this share is smaller in the modern macroeconomy (post-1984) than in the past. Fed policy is marginally more important for services inflation but only at longer horizons (3 years and beyond), and usually between 10 to 15% of total variability since the Great Recession. At all horizons and for all PCE metrics, supply factors are far more important in determining inflation than monetary policy. In some cases, especially at longer horizons, even demand factors outweigh monetary policy in determining inflation.

This is largely in line with points I have been arguing since last year—namely, that the Fed’s manipulations of the federal funds rate have had little if anything to do with declines in consumer price inflation.

We do well to remembe that the core myth informing the Fed’s strategy—that Paul Volcker’s federal funds strategy in the early 1980s “cured” hyperinflation—is not supported by the historical evidence.

Even in the present circumstance, the markets are steadily rebuking Jay Powell’s interest rate ambitions, with market interest rates having broadly declined over the past several weeks.

When interest rates are falling in the face of persistent Quantitative Tightening, that is a sure sign that what is transpiring is not inflation coming under control but the economy steadily spinning out of control, and into a deeper (and potentially longer lasting) recession.

We are seeing more and more confirmation that the economy is backsliding with the October Consumer Price Index data as well as that of the October Producer Price Index.

Nor was any of this either inevitable or unavoidable. From the start of the Pandemic Panic Recession it was immediately obvious just from the extant data at that time that the policies pursued by both the federal government and various state governments with regards to COVID-19 were counterproductive and economically disastrous.

First the Federal government and then the Federal Reserve with their misguided and misbegotten policies created economic turmoil, and ever since have persisently mismanaged and mis-stated their handling of that turmoil. Ever the propagandistic handmaiden to the authoritarians at all levels of government, the corporate media has dutifully compounded the problem by presenting delusional assertions that all is well with the US economy, that labor markets are prosperous and strong, and that the good times are not just around the corner, but actually here.

In every particular, the Federal government, the Federal Reserve, the many state governments, and the corporate media have been doggedly and obsessively mistaken in their policies and their pronouncements. At every turn, the “experts” have simply been about as wrong as it is humanly possible to be.

It is time for the “experts” in the government and in the corporate media to sit down and shut up. They created this economic mess, and they are failing miserably at cleaning it up. True to Ronald Reagan’s pithy observation over forty years ago, these “experts” are not any sort of economic solution; rather, they are the core of our economic problems.

Kedia, J. Has Fed Policy Mattered for Inflation? Evidence from Monetary VARs. 8 May 2023, https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/2023-05/working-paper-76_0.pdf.