Jay Powell and the FOMC have a dilemma on their hands.

Do they raise the federal funds rate yet again, trying yet again to push interest rates higher, and risk catalyzing more bank runs, more liquidity crises, and more financial panic?

Do they lower the federal funds rate, allowing interest rates to retreat, easing pressure on banks, and risk reigniting largely cooling consumer price inflation?

Do they stand pat, neither raising nor lowering the federal funds rate, risking both more bank runs and more consumer price inflation?

Further economic chaos and turmoil are the potential consequences of every alternative before them, so which one is the best one?

Ages ago, back before the sudden serial collapses of Silvergate Capital, Silicon Valley Bank, and Signature Bank of New York triggered a spasm of global banking crisis, the challenges before Jay Powell centered on resolving the dichotomy between headline data indicating a robust US economy and supportive details telling the exact opposite story.

Rising unemployment numbers had to be reconciled to reports of stellar job creation.

Official (and arguably false) BLS employment statistics which exceeded other independent job creation metrics needed to be assessed against the backdrop of the Fed’s ongoing war against high consumer price inflation.

This was the state of the debate just two weeks ago over the Federal Reserve’s inflation-fighting strategy of raising interest rates to trigger a general recession that would bring down consumer price inflation.

Then the bank failures erupted and scrambled everyone’s thinking on interest rates and inflation.

Suddenly the concern was whether banks had enough money, enough liquidity, and enough time to beg or borrow the funds they did not have.

Perversely, the Fed’s allegedly anti-inflation interest rate hikes helped catalyze the very bank failures and liquidity crises which are now complicating any future interest rate hikes.

From the outset, the bank failures have presented a conundrum for Powell.

For the last year, the Federal Reserve has tried to accomplish one goal, using one tool — lower inflation by raising interest rates.

The result has been benchmark interest rates rising by 4.5% in a year and headline inflation falling from a peak of 9.1% in June to 6.4% as of January. As Fed Chair Jerome Powell reiterated in testimony on Capitol Hill this week, there is still work to be done for the Fed to achieve its goal.

But over the last week, acute challenges at two banks have surfaced another issue now facing the Powell Fed. And that is the stability of the financial system.

On Wednesday, Silvergate Capital (SI), which had become one of the crypto industry's biggest banking partners, announced it will liquidate and wind down operations after suffering significant deposit outflows from its digital asset clients.

That same day, Silicon Valley Bank (SIVB), the preferred banking partner of the venture and startup worlds, announced it would take a $1.8 billion loss while liquidating its entire short-term securities book and raising $2.25 billion fresh capital.

The significance of the bank failures was magnified by the speed with which they arose and the sheer size of the failures—SVB and SGNY were the second and third largest bank failures in US history.

More than $100bn has been wiped off US banks’ value as the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank continues to send shockwaves throughout Wall St.

Trading was temporarily halted in dozens of regional banks this morning as shares fell by up to 75 percent, despite Joe Biden’s assurances that ‘US banking is safe.’

Major US banks were also affected by the crash as fear spread throughout the market, with Wells Fargo plummeting 7.5 percent, Bank of America falling 7.4 percent, Citigroup plunging 5.8 percent and JP Morgan down 2.7 percent.

US President Joe Biden insisted that the system was safe after the second and third largest bank failures in the nation’s history happened in the span of 48 hours.

Within a matter of days, the banking turmoil completely upended even Wall Street’s thinking on what the Federal Reserve would do next, with expectations of a 50bps rate hike on March 10 evaporating within days, to be replaced by uncertainty over whether the Fed would hike by only 25bps or not hike at all.

Prior to last week’s bank closures, it was considered almost a given that a 50bps rate hike was in the works. As of March 10, the CME Group’s FedWatch tool viewed the 50bps rate hike as the most likely alternative.

As of yesterday, Wall Street believes the 50bps rate hike is off the table, and there is a growing possibility the Fed will not raise the Federal Funds rate as all.

Wall Street’s most recent sentiments are leaning towards the Fed hiking the federal funds rate by 25bps.

Part of Wall Street’s angst is that it constantly frets that interest rate hikes by the Fed tend to end in either recession or financial crisis (which then leads to recession).

When the Federal Reserve is raising interest rates, as it is now, recession is always a risk. And slumps tend to come suddenly after an unexpected shock deals a blow to confidence during a particularly vulnerable time.

“The combination of the Federal Reserve trying to slow things down to deal with inflation, financial conditions tightening and then—under the stress—you’re going to see some breakage,” says Peter Hooper, global head of economic research for Deutsche Bank AG.

This worry, of course, completely blows past the reality that the Fed’s own stated rationale for the interest rate hikes is to catalyze a recession (and possibly a financial crisis leading to recession). Not only has Jay Powell said so, but the Federal Reserve bank presidents have said so—explicitly, and repeatedly, as Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin said bluntly last year.

However, further on down, Barkin said the quiet part out loud about what “whatever it takes” really means (emphasis mine).

Barring an unanticipated event, I see rising rates stabilizing any drift in inflation expectations and in so doing, increasing real interest rates and quieting demand. Companies will slow down their hiring. Revenge spending will settle. Savings will be held a little tighter. At the same time, supply chains will ease; you have to believe chips will get back into cars at some point. That means inflation should come down over time — but it will take time.

Let that bit sink in. The reason rate hikes “work” to cure inflation is that rising interest rates make the cost of credit (aka, the “cost” of money) too high for consumers to utilize. Consumers are forced to spend less. Along the way, a few jobs are wiped out, a few workers are laid off, and eventually prices come down.

Powell’s dilemma now is has he sufficiently catalyzed a recession, or does he need to inflict still more damage on the economy to get the recession he thinks he needs to corral consumer price inflation?

Certainly Bloomberg macro strategist Simon White, appearing in ZeroHedge last week, seemed to think enough damage had been done.

The collapse of SVB and the turmoil at Credit Suisse will turbo-charge the effects of QT, sealing the case for a US recession that remains underpriced by equity and credit markets.

Remember QT? To misquote Dirty Harry: in all this excitement, it’s easy to lose track of what’s going on. But quantitative tightening’s effects are now likely to accelerate as banking stress causes a steeper fall in bank reserves, tipping the economy into a potentially deep recession.

Hedge fund manager Bill Ackerman, head of Pershing Square Capital Management, was positively panicked about the possibility of the wheels coming off the banking system yet again, all but demanding massive government intervention to stop what the government intervention had worked to set in motion.

Ackman, who runs Pershing Square Capital Management, and is not averse to an apocalyptical outburst, said the banking sector needed a temporary deposit guarantee immediately until an expanded government insurance scheme is widely available.

“We need to stop this now. We are beyond the point where the private sector can solve the problem and are in the hands of our government and regulators. Tick-tock.”

What does the data say?

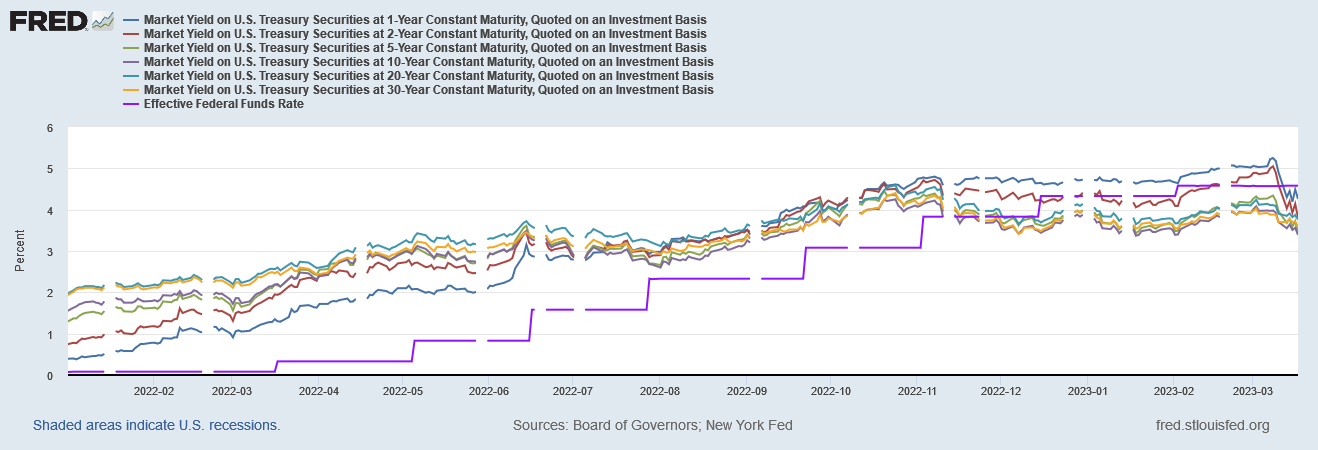

The most glaring thing the data says is that Powell has been something of a failure at raising interest rates. The FOMC keeps raising the federal funds rate, while Treasury yields largely stopped rising after November’s rate hike.

Yields have cratered during the recent turmoil, and are lower now than they have been in months—without Powell lowering the federal funds rate by so much as a basis point.

It makes no sense to speak of Powell increasing interest rates when interest rates are demonstrably not increasing.

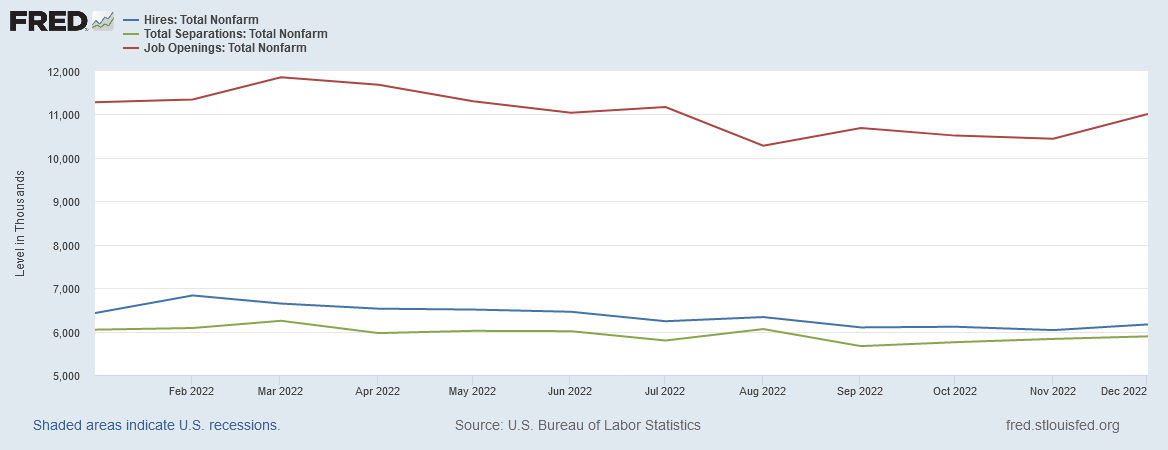

Meanwhile, despite the corporate media narrative, not only have US labor markets not been red hot of late, they have been cold and arguably glaciating.

The data is quite clear that hiring in 2022 declined.

Employment overall has only grown 1% in the past three years.

While one could argue the extent to which the Fed’s rate hikes can claim credit for the deteriorating employment situation in the US, one cannot plausibly argue that the employment situation is not deteriorating—a reality that is only emphasized by the minimal improvement in the labor force participation rate.

While the employment situation is deteriorating in the US, so too is consumption—the primary driver of the US economy.

Adjusting for inflation, retail sales in the US went stagnant in 2022.

Meanwhile, wages—which fund most of America’s consumption—have been declining in real terms.

Has Jay Powell and the Fed caused enough damage already to trigger a recession? Certainly the data makes a compelling argument that they have.

Yet recession is not the only economic damage that has been done.

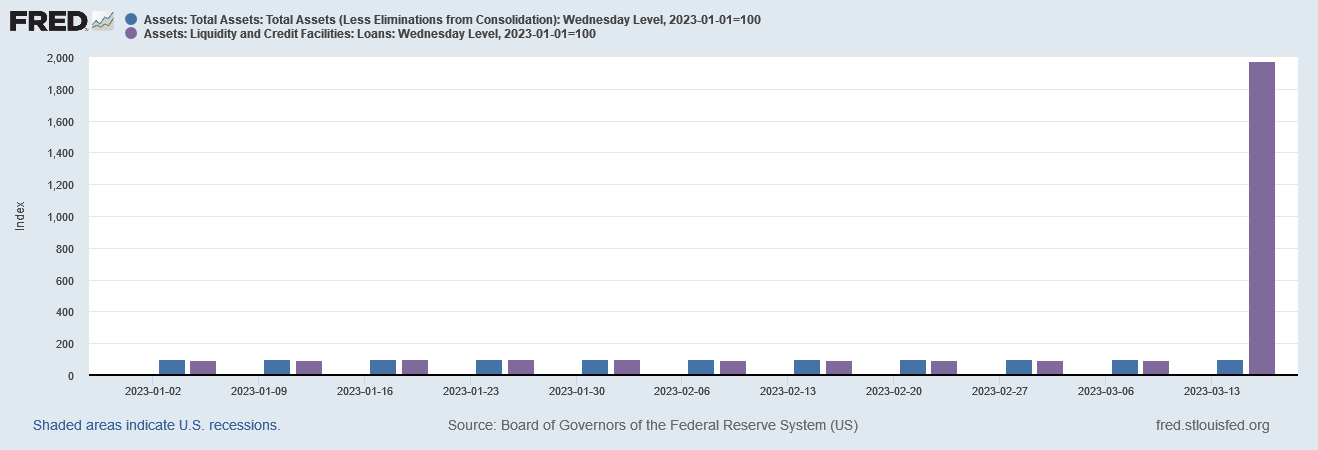

Most notably, as a direct consequence of the government’s response to Silicon Valley Bank’s abrupt closure, the Federal Reserve has greatly expanded its balance sheet—which it has been working to shrink of late—as banks have scrambled to borrow at the Fed discount window to cover ongoing and potential outflows of deposits.

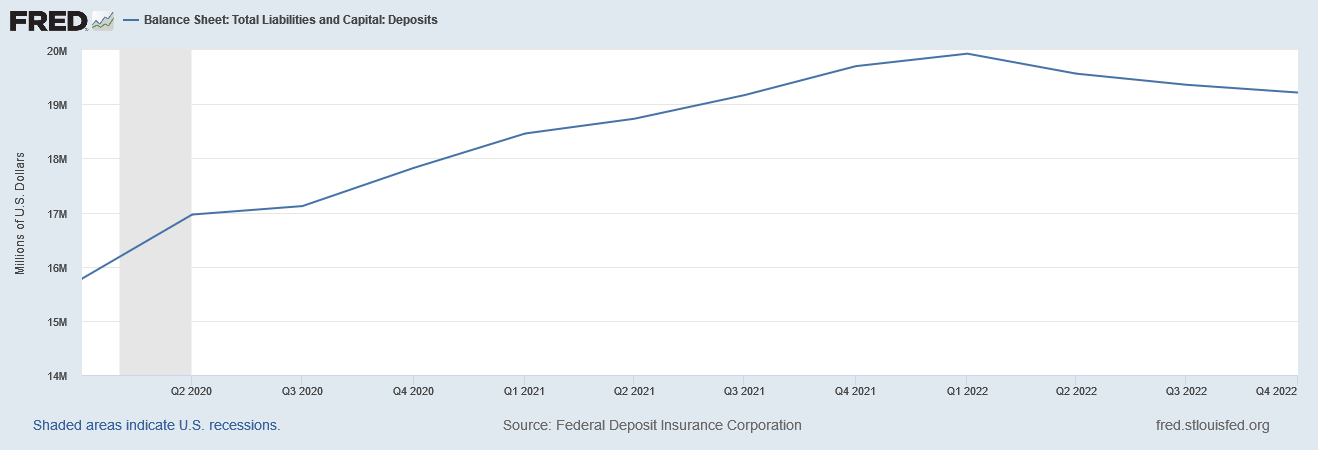

While it has only garnered media attention after the recent bank failures put the topic on the media radar, the reality is that bank deposits overall declined throughout 2022.

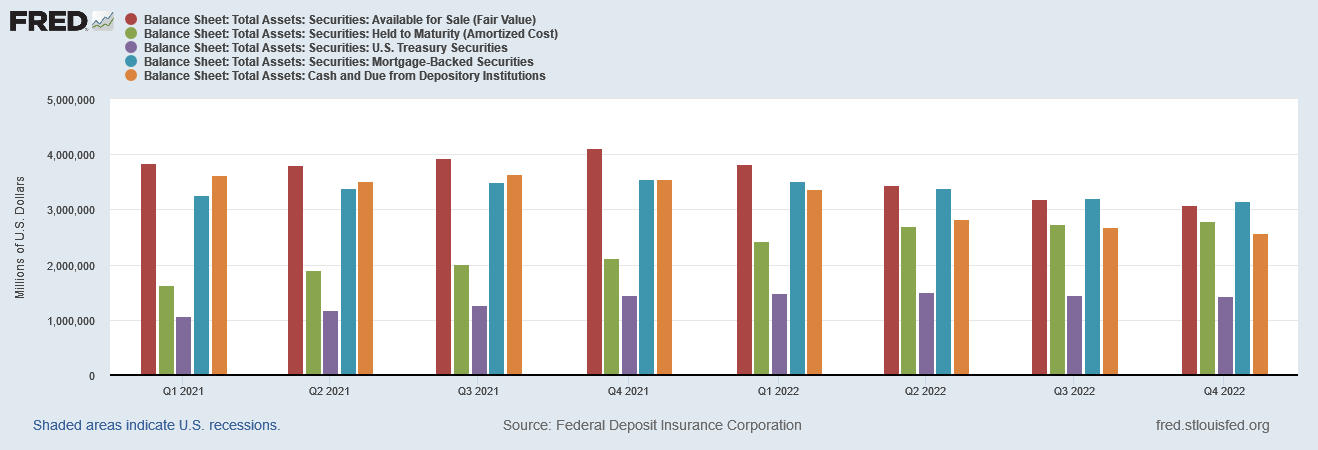

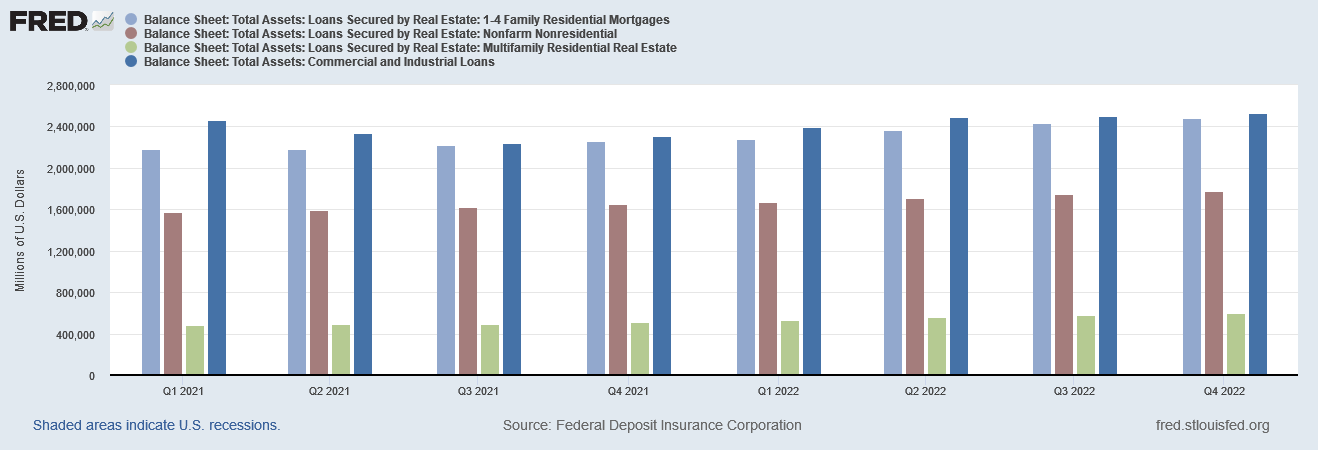

Complicating the situation is the growing disequilibrium on bank balance sheets, with securities and cash—notionally “liquid” investments—declining while loans have been increasing.

With less cash and fewer notionally liquid securities to cover the general trend in deposit outflows, and with legacy holdings of securities as well as loan books having largely negative market value due to rising interest rates (which puts the interest rates of the assets on the books below where the market is, and thus erodes their market value), the banking sector as a whole is demonstrably in a fragile state.

The fragility is disturbingly quantified by economist Erica Jiang’s recent research into bank assets which found the market value of bank assets is underwater to the tune of $2 Trillion1.

We analyze U.S. banks’ asset exposure to a recent rise in the interest rates with implications for financial stability. The U.S. banking system’s market value of assets is $2 trillion lower than suggested by their book value of assets accounting for loan portfolios held to maturity. Marked-to-market bank assets have declined by an average of 10% across all the banks, with the bottom 5th percentile experiencing a decline of 20%. We illustrate that uninsured leverage (i.e., Uninsured Debt/Assets) is the key to understanding whether these losses would lead to some banks in the U.S. becoming insolvent-- unlike insured depositors, uninsured depositors stand to lose a part of their deposits if the bank fails, potentially giving them incentives to run. A case study of the recently failed Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is illustrative. 10 percent of banks have larger unrecognized losses than those at SVB. Nor was SVB the worst capitalized bank, with 10 percent of banks having lower capitalization than SVB. On the other hand, SVB had a disproportional share of uninsured funding: only 1 percent of banks had higher uninsured leverage. Combined, losses and uninsured leverage provide incentives for an SVB uninsured depositor run. We compute similar incentives for the sample of all U.S. banks. Even if only half of uninsured depositors decide to withdraw, almost 190 banks are at a potential risk of impairment to insured depositors, with potentially $300 billion of insured deposits at risk. If uninsured deposit withdrawals cause even small fire sales, substantially more banks are at risk. Overall, these calculations suggest that recent declines in bank asset values very significantly increased the fragility of the US banking system to uninsured depositor runs.

This, in sum, is the minefield Jerome Powell and the FOMC have to navigate to reach a decision on interest rates.

While Wall Street is anticipating a 25bps increase in the federal funds rate, at this juncture the best move would be to just stand pat and neither raise nor reduce rates—and not say much at all beyond the fact that the Fed is neither raising nor reducing rates.

If the trend of interest rates since last November is not sufficient signal that raising the federal funds rate has diminishing impact on interest rates, the collapse in Treasury yields over the past week—which in effect “reset” interest rates to where they were at six months ago—should serve as glaring confirmation.

Regardless of what Powell wants to see happen with interest rates, and regardless of the impact interest rates have on inflation, the markets are making their interest rate preferences known—and markets do not want interest rates to move still higher, at least not yet.

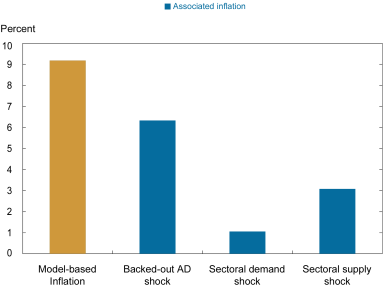

It is worth recalling the significance of Fed economist Julian di Giovanni’s analysis2 of the factors driving consumer price inflation, and his finding that only 60% of consumer price inflation has been demand-driven, with the other 40% arising from supply-side forces (which are beyond the influence of interest rates).

If this assessment is correct, then the portion of inflation amenable to interest rates has already been excised from the economy.

If we look at where market yields for various Treasury maturities are at currently, and compare them to the percentage rate equal to 60% of headline consumer price inflation, we see the lower-yield interest rates have already risen above where 60% consumer price inflation would be.

If we posit that inflation will continue to decline, than by the end of December, 60% of headline consumer price inflation will be lower than most if not all of the lower end of the yield curve.

While it would be a jarring and abrupt reversal for Powell to declare a victory over inflation, 60% of current inflation would have come in below at least some portions of the yield curve prior to last week’s collapse in yields.

Arguably, consumer price inflation—or at least that part of it which can be moderated through interest rate manipulations—is either close to or already beneath current interest rates. If that is the case, then real yields become positive—something they have not been for a number of years—and there is no more case for pushing rates higher. Once real yields are positive market forces should be allowed to do the rest of the work on restoring pricing equilibrium and curtailing consumer price inflation.

To fully untangle the banking mess that years of reckless, feckless, and demonstrably insane Federal Reserve monetary policy has created will take quite some time—years if not decades. Actively triggering further economic instability in the name of pursuing overall price stability does little to further that process, and might even create a worse mess. Pushing rates up or pushing rates down are both likely to risk that further economic instability.

With Wall Street and the banking sector already agitated and disrupted, adding to the agitation and disruption with further interventions is not a move that is likely to end at all well. Doing nothing becomes the best move of the moment.

Jiang, E., et al. “Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs?” SSRN, 2023, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4387676.

Di Giovanni, J. How Much Did Supply Constraints Boost U.S. Inflation? . 24 Aug. 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/08/how-much-did-supply-constraints-boost-u-s-inflation/

"There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved."

Which will it be, Mr. Powell?

One personal result of the past few years is that I’ve become a lot better at spying propaganda in the media, and boy, it’s been nothing but propaganda this past week about the banking crisis. Every adjective, every adverb, every innuendo has been ‘nothing to see here, no big deal, crisis averted’. The newspaper buries the articles on inner pages, and refers to the banking crisis in the past tense, as if there’s no possibility of more turmoil. The same media that practically screams about racial inequity and trans oppression talks soothingly about Credit Suisse going under, with less concern than if a local grocery store was closing.

Thank heavens for Substacks like yours, Mr Kust.

By the way, have you read Bad Cattitude’s Substack today?