Do Something? Or Just Stand There?

The Fed Should Continue To Do Nothing. Naturally It Will Do Something

Long time readers are by now well familiar with my arguments on the sheer wrongheadedness of the Federal Reserve’s strategy on consumer price inflation of raising the federal funds rate.

However, my disaffection with their strategy has not dissuaded them at all, as the Fed seems determined to press forward with not just one but at least two more rate increases, regardless of what the data actually has to say.

The Federal Reserve will need to implement two more quarter-point rate rises this year to bring inflation under control, a top official at the US central bank said on Thursday.

In an intervention that pushed back against market pricing suggesting the Fed will conclude its monetary tightening after just one more increase, Christopher Waller backed a rise this month and another before the end of 2023.

More federal funds rate increases appear to be “baked in”, regardless of what the data might indicate—and regardless of the Fed’s assurances that its decisions are “data driven”.

In assessing the appropriate stance of monetary policy, the Committee will continue to monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook. The Committee would be prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge that could impede the attainment of the Committee's goals. The Committee's assessments will take into account a wide range of information, including readings on labor market conditions, inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and financial and international developments.

The inflation data is in, the inflation data does not say “more rate hikes”, but the Fed is going to hike rates anyway. Because “data”. Because “reasons”. Because “well….just because.”

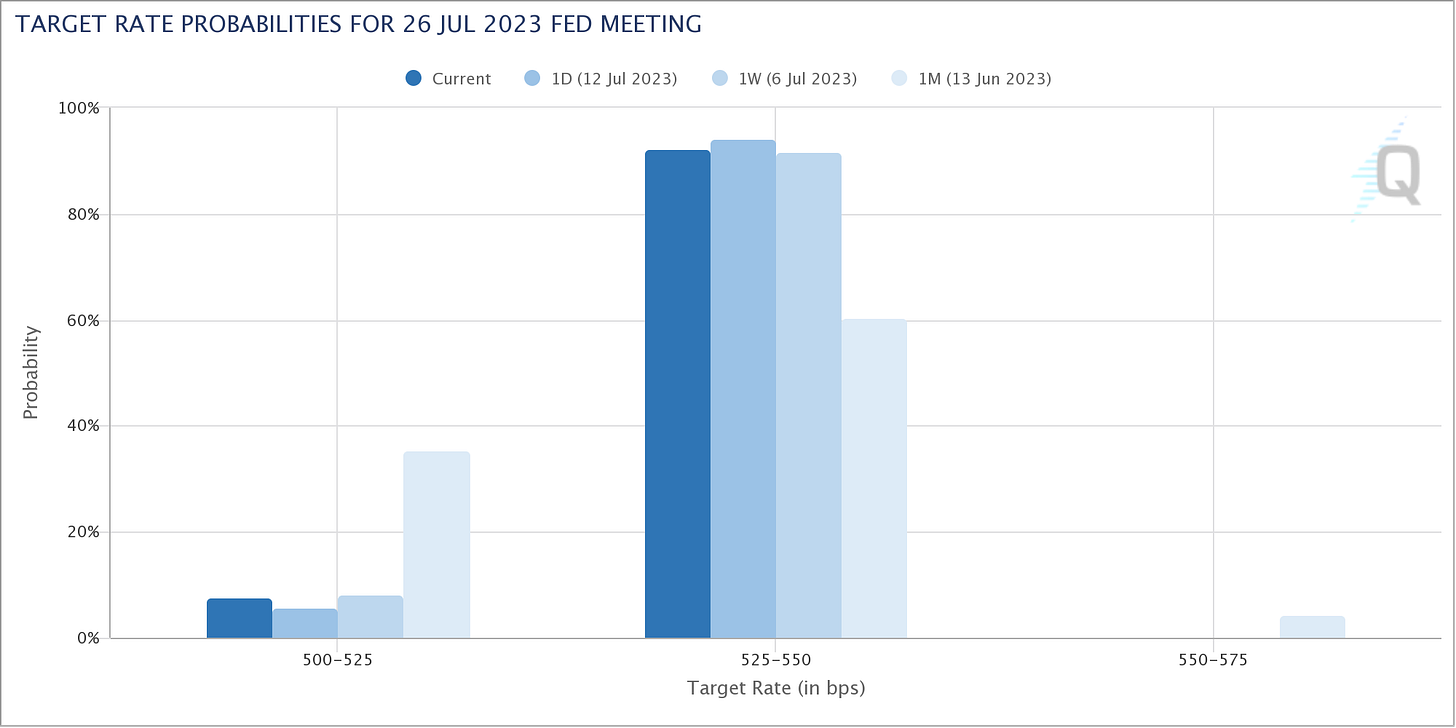

For its part, Wall Street fully expects the Fed to raise the federal funds rate another 25bps when it meets at the end of the month.

Wall Street was already heavily persuaded that the Fed was going to goose rates after the last FOMC meeting, and it has only become even more certain of a rate hike since then.

This outlook is in spite of perspectives such as that of Moody’s Chief Economist Mark Zandi, who this week tweeted out that the latest inflation report made a strong case against rate hikes.

It is interesting to note that Zandi appears to take a cynical view of the inflation report itself (“overstates the case”), but agrees that inflation is coming down, thus further rate hikes are not warranted. While I am uncertain of how good a report on June’s consumer price inflation we actually got, I do agree with Zandi that the report gives no support for more rate hikes.

Thus there is a very real risk of the Fed overshooting and tipping the economy into overall outright deflation. This risk is compounded by the reality of an ailing global economy, with demand shrinking in Europe as well as in China.

Nor is this view isolated to just myself and Mark Zandi. London School of Economics professor and 2010 Nobel laureate Christopher Pissarides also advocates a “wait and see” approach.

“It takes time for these to have their full effect, so given that inflation is moving in the right direction, that interest rates are high, I would just wait and see what happens next,” Pissarides, a professor at the London School of Economics, told CNBC’s “Street Signs Europe” on Thursday.

In spite of such “authoritative” perspectives, Wall Street is convinced that the Fed is going to raise the federal funds rate anyway. After all, Jay Powell has consistently said that at least two more rate hikes were on deck for 20231.

At our last meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5 to 5-1/4 percent while continuing the process of significantly reducing our securities holdings. We made this decision in light of the distance we have come in tightening policy, the uncertain lags in monetary policy, and the potential headwinds from credit tightening. As noted in the FOMC's Summary of Economic Projections, a strong majority of Committee participants expect that it will be appropriate to raise interest rates two or more times by the end of the year.

Jay Powell would appear to have accomplished at least this much: Wall Street is giving him maximum credibility on what the Fed will do.

However, simply because the Federal Reserve is likely to raise the federal funds rate does not mean that the federal reserve should raise the federal funds rate. When one unpacks all of the data, including the latest inflation and jobs reports, there simply is not a good case to be made within that data for further rate hikes.

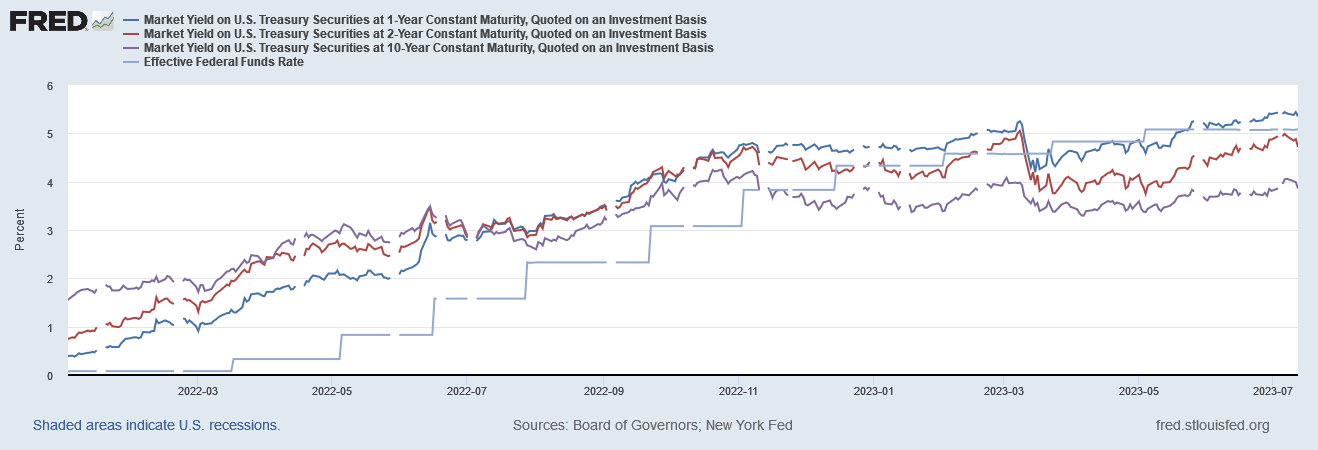

The strongest argument against more rate hikes is the reality that the rate hikes have not been at all influential in pushing market interest rates higher going back to at least last November. When you look at the longer term Treasury yields, they largely stopped rising at the time of the November, 2022 rate hike.

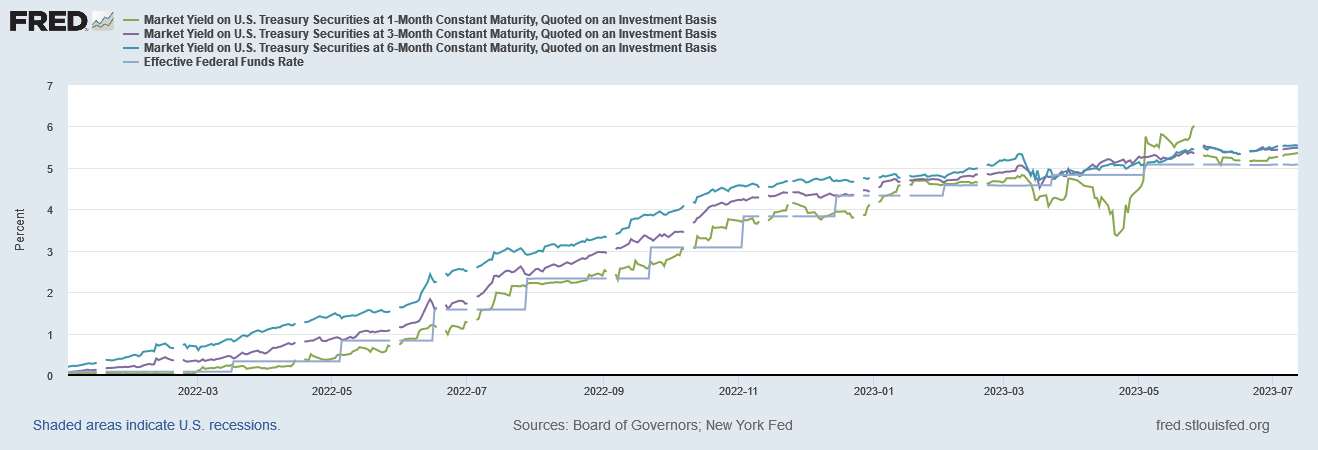

While short term yields have continued rising, their increase greatly slowed after November.

Moreover, as both charts show, in the wake of the Silicon Valley Bank collapse, yields abruptly nosedived, and the longer term yields have not really risen again since. The 10 Year Treasury yield was 3.98% on March 8, and only briefly flirted with the 4% threshold on July 7 before retreating again to 3.86% on July 12.

The 10 Year Treasury yield ended the week almost exactly where it was at the beginning of the year: 3.86% vs 3.88% on December 30 of last year. There have been three federal funds rate hikes this year. Not one of them has has pushed long term yields higher.

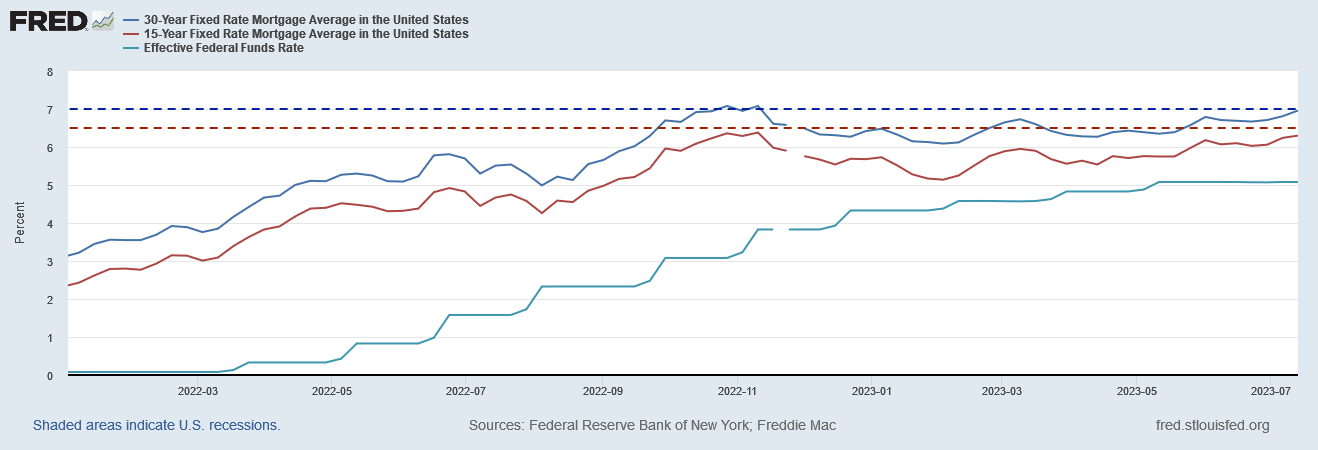

But it is not merely Treasury yields that are not responding to the Federal Funds rate any more. Mortgage rates similarly plateaued last November and have remained there despite increases to the federal funds rate.

As of this writing, the 30-Year mortgage rate has effectively had a ceiling rate of around 7%, and the 15-Year mortgage rate has effectively had a ceiling rate of 6.5%.

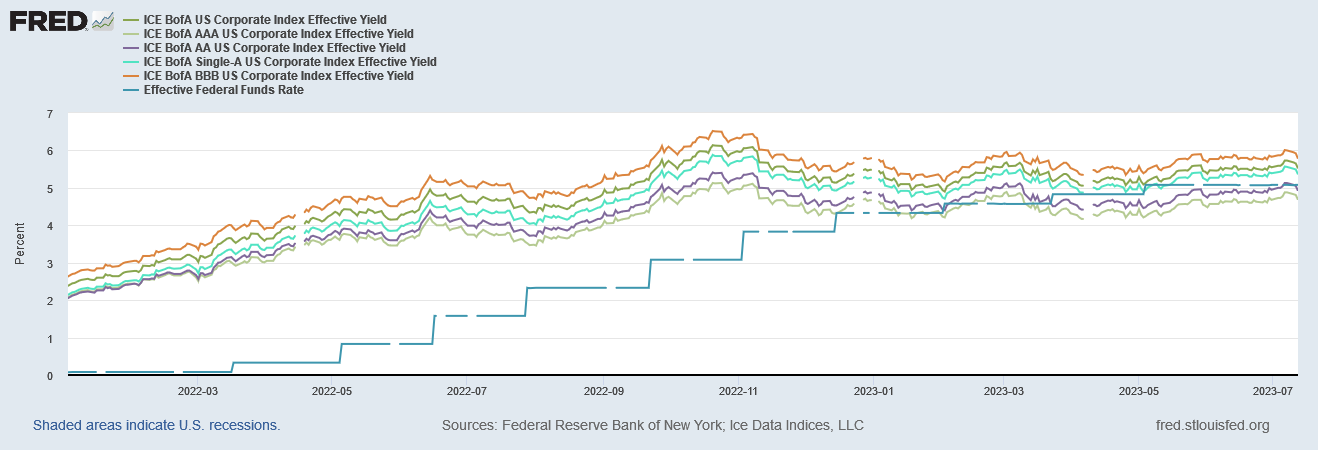

We see the same thing with investment-grade corporate debt.

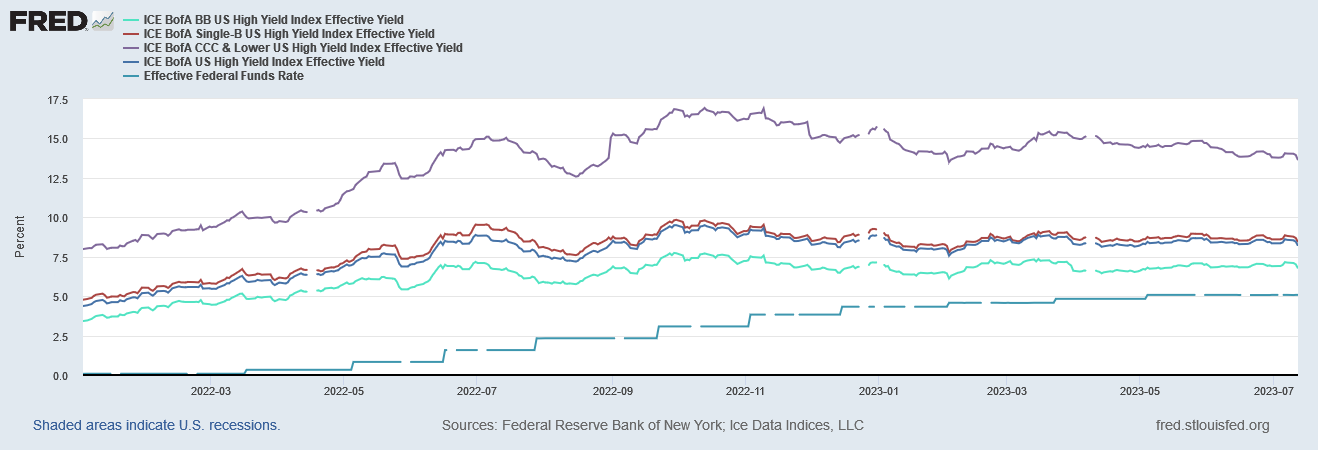

If anything, high yield (“junk”) corporate debt plateaued even earlier, around July.

The one thing the federal funds rate has clearly not done is push market interest rates higher—which is the primary reason for raising the federal funds rate.

When the Fed raises the federal funds target rate, the goal is to increase the cost of credit throughout the economy. Higher interest rates make loans more expensive for both businesses and consumers, and everyone ends up spending more on interest payments.

It is impossible to increase the cost of capital in the marketplace when market interest rates refuse to increase.

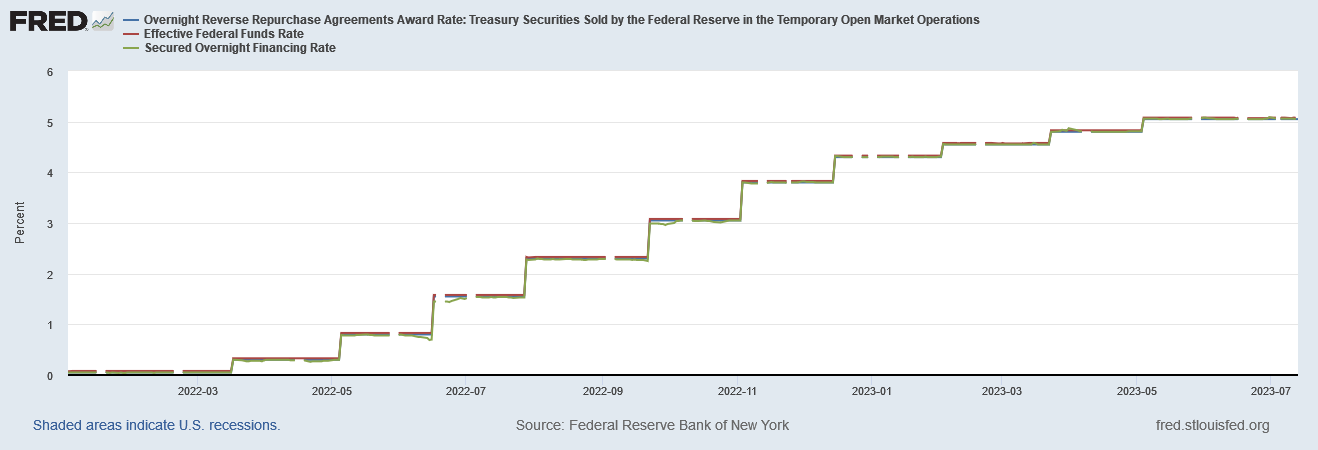

About the only rates that are getting pushed up by the federal funds rate are the Secured Overnight Financing Rate and Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreements Award Rate—which invariably align with the Federal Funds Rate.

The only interest rate likely to be pushed up by the Federal Reserve is the one it pays to participants in its reverse repo facility.

Increasing rates in the reverse repo facility are a bad idea. Up until recently, pushing up the reverse repo rate has correlated with bringing down the level of deposits in the banking system.

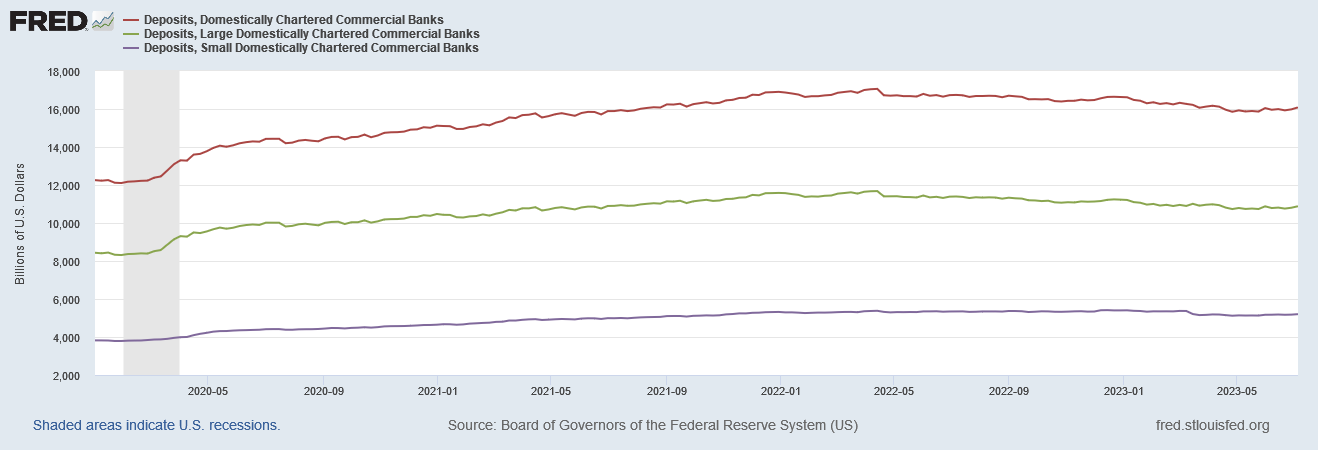

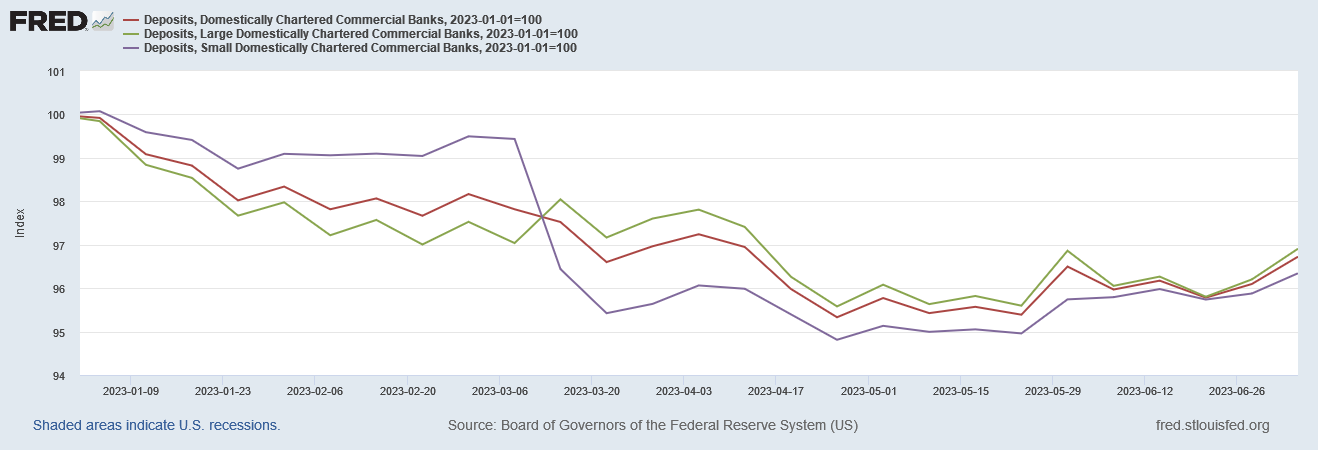

Bank deposits peaked in April of 2022, just after the Fed began its push to raise interest rates. After about April 13 of last year, deposits across domestically chartered banks began a sustained decline.

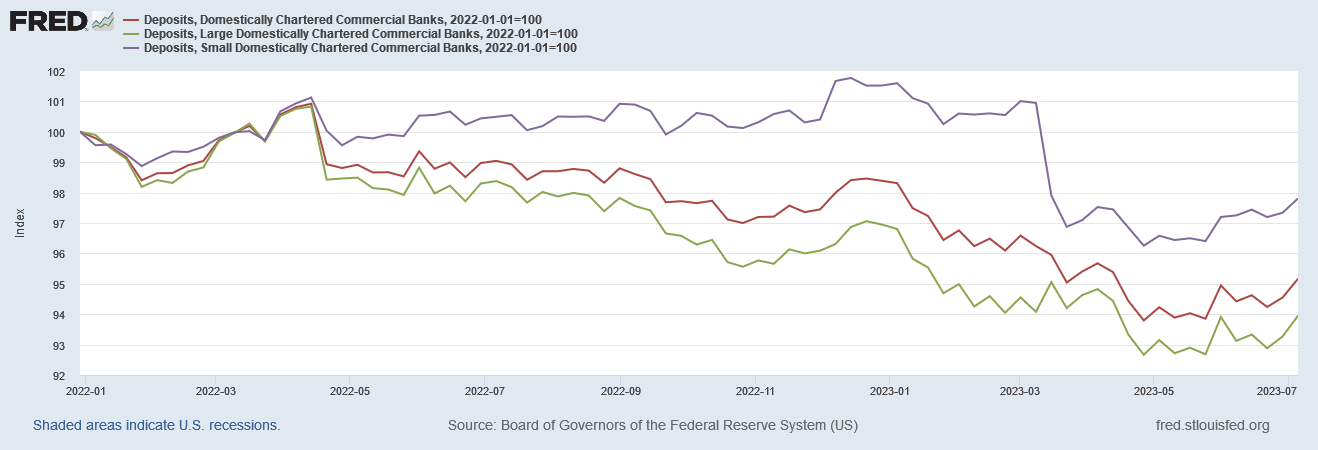

Tellingly, the deposit decline has been most pronounced at the country’s large domestically chartered banks, with the smaller banks actually bucking the trend until the Silicon Valley Bank collapse this past March, as can be plainly seen when we index bank deposits to January 1, 2022.

Arguably, the federal funds rate hikes contributed to SVB’s collapse, which was the result of a liquidity crisis brought on both by declining deposits and mounting losses in its Hold-To-Maturity portfolio of Treasuries.

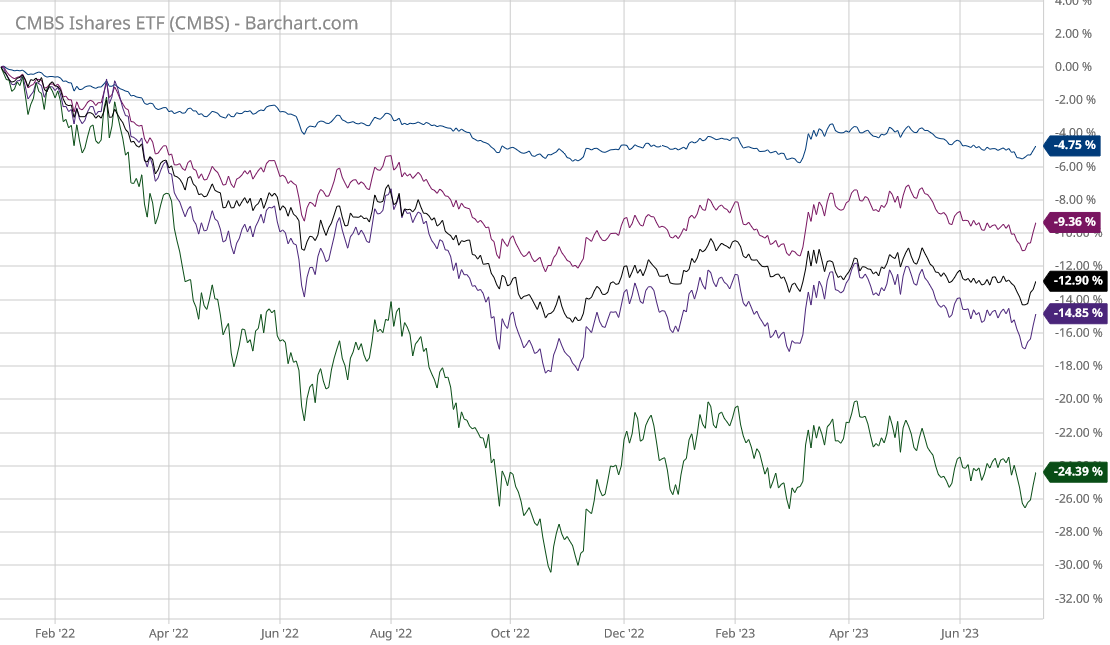

Nor is there any real doubt that the Fed’s rate hikes catalyzed the loan losses in SVB’s securities portfolios. A survey of exchange traded funds (ETFs) focused on Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities shows the market value of previously purchased (i.e., low yield) securities dropping precipitously throughout 2022, stabilizing only around November—the time frame when interest rates stopped responding to the federal funds rate hikes.

This was, of course, both eminently predictable and predicted, with warning signs appearing as early as December of last year.

One of my main arguments against the rate hike strategy from the outset has been that the strategy was all but guaranteed to produce a liquidity crisis.

The serial banking collapses of this past spring are the proof that it should be an expected consequence.

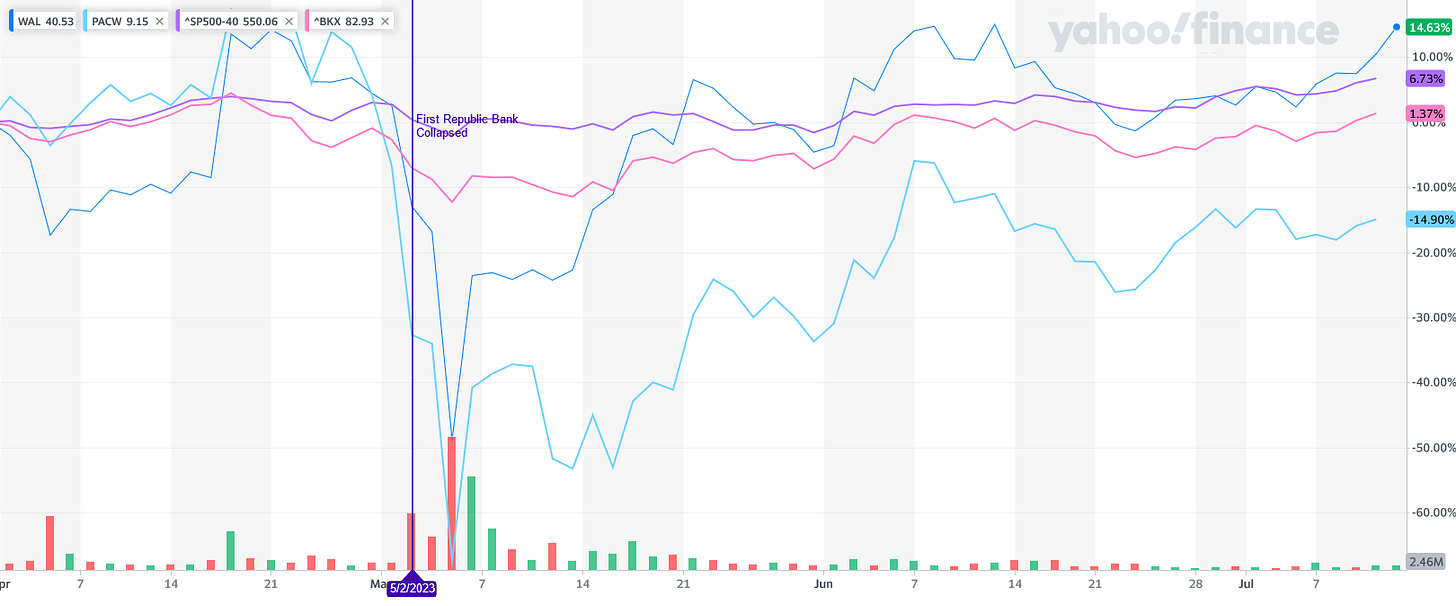

Moreover, bank stocks along with deposit outflows did not ameliorate until last month—when the Fed opted to hit “pause” on further rate hikes. Two of the banks most expected to be the next banking dominoes to fall—PacWest Bancorp and Western Alliance Bancorp—began to see their stock prices recover in May, first on the hope and then on the certainty that the Fed would not push through more rate hikes.

That the banking system itself breathed a sigh of relief can be seen in the bottoming out of deposit outflows in this same time frame. As we can see when we index deposits to January 1 of this year, recently bank deposits have actually began increasing again.

Raising the federal funds rate at the next FOMC meeting very likely would catalyze a further decline in bank deposits, would certainly catalyze further losses in securities portfolios, and the combination of the two could very easily catalyze a new liquidity and then banking crisis. It might not happen right away, but with the Fed asserting more than one rate hike, Wall Street is likely to price in another rate hike, which means expectations will be set to push deposits and securities portfolio valuations down further, and in such an environment the only banking question left outstanding will be “Which bank falls first?”

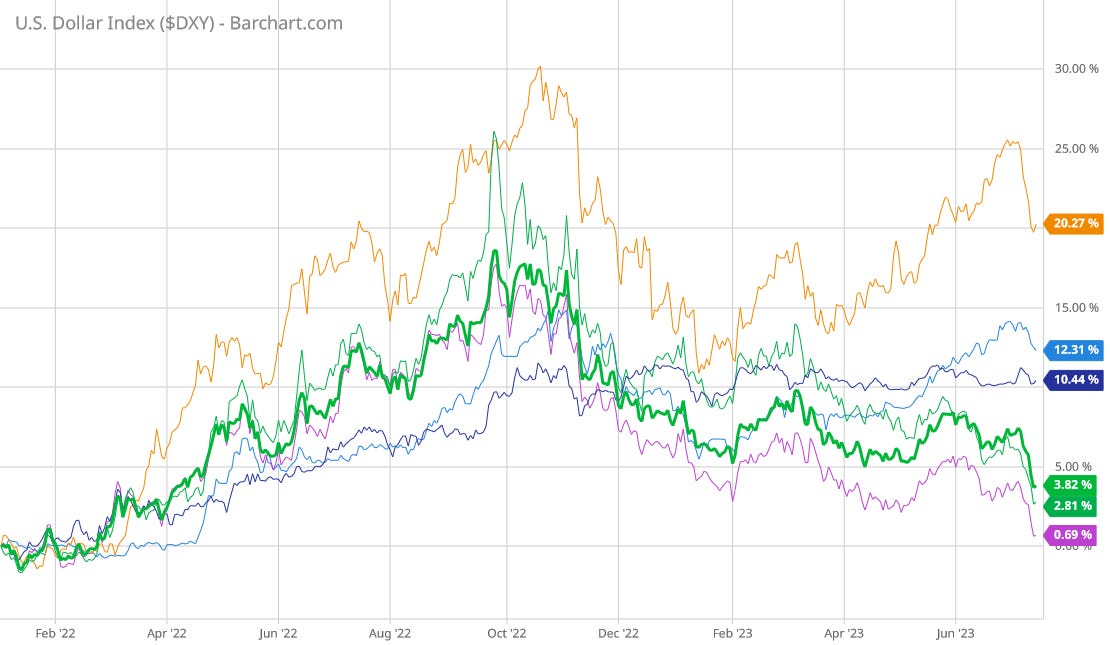

There is only one justification for raising rates at this time, and, withal, it is a mighty thin justification: to defend the dollar.

For better or worse, forex markets have been gauging the relative worth of the major currencies based on the rate hike actions of their respective central banks. One positive effect of the Fed’s rate hikes last year was that the dollar appreciated significantly against other currencies.

It is notable that the dollar’s appreciation ended at about the same time market interest rates plateaued last November. If the Fed’s next rate hike fails to move the needle on Treasury yields (highly likely), that hike may not be all that helpful in maintaining the dollar’s strength.

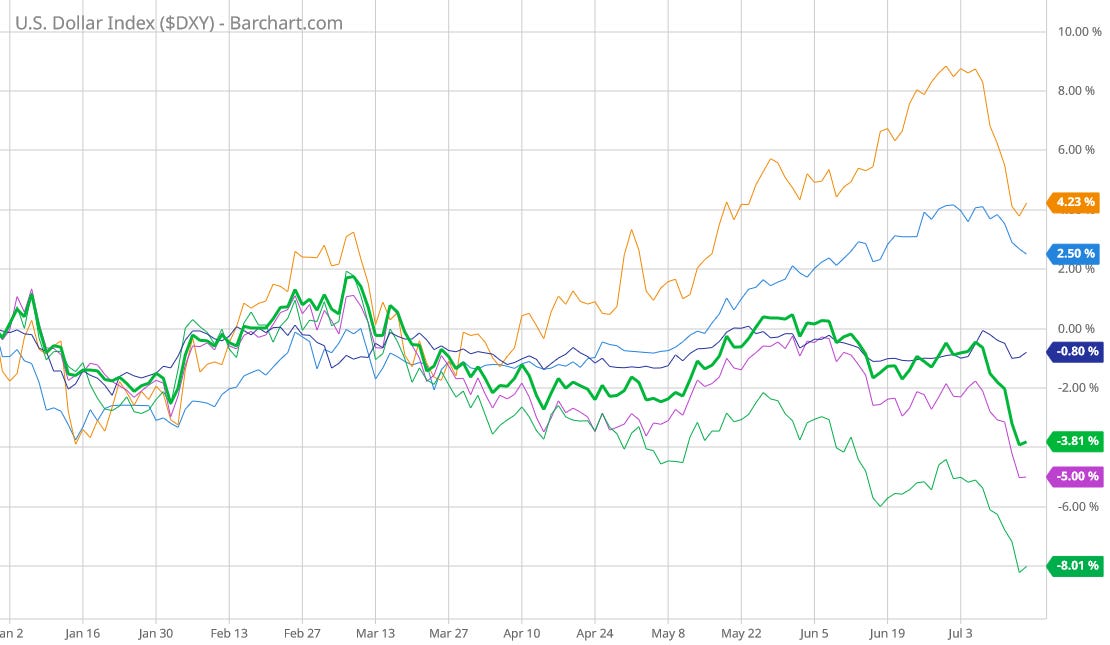

The recent inflation data, coupled with a forex sentiment that the Fed will not raise rates, apparently catalyzed further decline in the dollar last week, with the inflation reports certainly not helping.

Currency markets are anticipating the Fed won’t raise rates. Some currencies, such as the Indian rupee, are trading higher specifically on that expectation alone.

The Indian rupee is poised to rise on Thursday on expectations that cooling inflation in the United States will allow the Federal Reserve to pause interest rate hikes soon.

Non-deliverable forwards indicate the rupee will open at around 82-82.05 to the U.S. dollar compared with 82.2475 in the previous session. The local currency has now almost recouped all the losses it suffered last week.

"Having talked of an upside breakout (for USD/INR) last week, this has been quite a turnaround," a fx trader said.

With the dollar weakening against other currencies—particularly the Chinese yuan—a 25bps rate hike at the end of the month could be sufficient to at least halt the dollar’s weakening against other currencies.

While raising the federal funds rate may help strengthen the dollar—and that is hardly a guarantee, given the movements of the dollar even before the Fed’s “pause” last month—strengthening the dollar alone is hardly adequate justification for raising rates. It certainly will not help the dollar in forex markets if we see a return to the liquidity and banking crises of this past spring.

As we can see from the data, a renewed banking crisis is not merely possible, it is at least to some degree probable. A renewed rate hike could easily tip PacWest and Western Alliance into insolvency—their stocks might have been rising of late, but that should not be considered proof they are prepared to weather another deposit run. Nor do we know for certain how many other banks might be impacted, should we see a replay of this past spring. We do know that other banks are vulnerable, as a survey of lending institutions by MarketWatch in the wake of SVB’s collapse shows.

The risk of a banking crisis plus the inability of the Fed to push market rates higher at this point are more than enough to offset the marginal benefits of providing additional market support for the dollar, and backstopping the dollar is the only justification within the data for further federal funds rate hikes.

When the Fed meets at the end of the month to decide what to do about interest rates, it would do well to remember the White Rabbit’s command to Alice just before she went down the rabbit hole: “Don’t just do something. Stand there!”

Alice was warned and didn’t listen. The Fed has been amply warned, but it is not likely to listen either.

Powell, J. Speech by Chair Powell on Financial Stability and Economic Developments. 29 June 2023, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20230629a.htm.

Do you have any thoughts on the “reasons” they are doing this? Is it political or just the usual bad Fed policy? Is it a conspiracy to ruin the economy or do they really think their plan is working? And doesn’t history show that this plan is too risky ? And considering the shaky state of geopolitics, it’s even more risky? Or are we just being worry warts ?

Maybe the feds are skeptical of their inflation reports like the rest of us?