JOLTS Report Says Nothing Has Changed. That's The Problem

Underneath, Weaknesses Continue To Accumulate

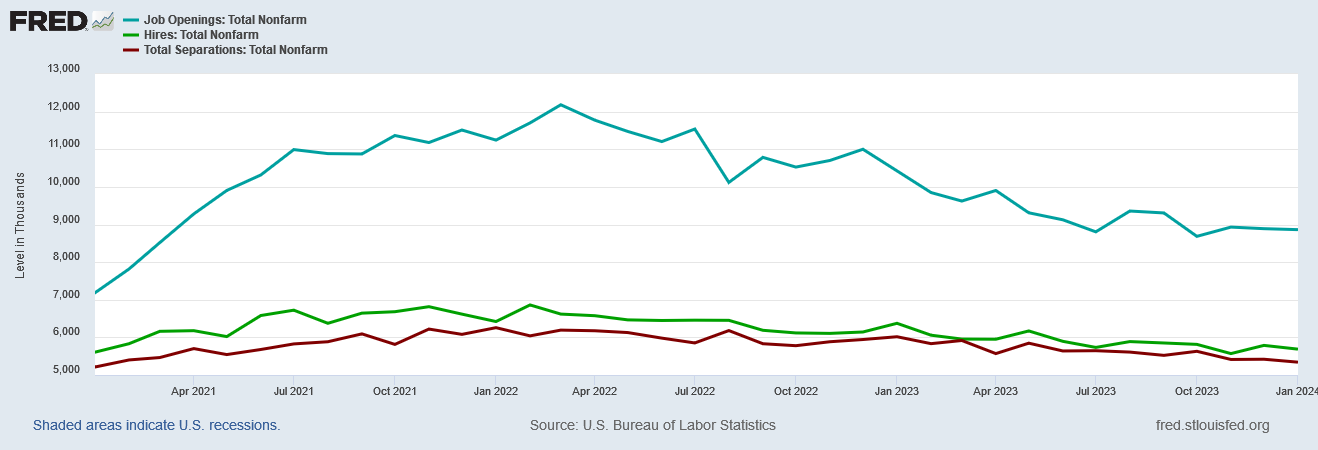

Whether the January Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary represents good or bad news ultimately depends on which narrative you accept—or how far back you peel the data onion. However, even the top level seasonally adjusted numbers all went in the same direction—ever-so-slightly down.

The number of job openings changed little at 8.9 million on the last business day of January, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the month, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively. Within separations, quits (3.4 million) and layoffs and discharges (1.6 million) changed little. This release includes estimates of the number and rate of job openings, hires, and separations for the total nonfarm sector, by industry, and by establishment size class. This release also includes 2023 annual estimates for job openings, hires, and separations.

“Changed little” means that the seasonally adjusted number of job openings declined, the seasonally adjusted number of hires decline, and the seasonally adjusted number of separations declined.

Job openings declining notionally suggests job markets are weakening.

Hiring declining notionally suggests employment itself is weakening.

Separations declining notionally suggests employment itself is strengthening, and so is the job market.

Does all three declining notionally suggest job markets and employment are strengthening or weakening? Certainly the corporate media is uncertain, with the reporting going both directions.

Yet when we peel back the layers of data, we see trends that are potentially far more troubling than what the headline numbers might indicate.

The confusion within corporate media is self-evident, when the same news stories speak of labor market conditions “easing” and labor markets remaining strong.

U.S. job openings fell marginally in January, while the number of workers quitting their jobs dropped to a three-year low, indicating that labor market conditions were gradually easing.

The decline in resignations, which pushed the quits rate to the lowest level in 3-1/2 years, over time bodes well for slower wage inflation and overall price pressures in the economy.

There were 1.45 jobs for every unemployed person in January up from 1.42 in December, indicating the labor market remains strong. This is well above the average of 1.2 during the year before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Those two narrative arcs run counter to each other, so there is a limit to how much credulity we may assign to them.

Even the “expert” forecasts undershot the JOLTS report, yet the reported job openings themselves touched a three-year low.

Job openings hit their lowest level since March 2021 in January, showing further signs of rebalancing in the labor market.

There were 8.86 million jobs open at the end of January, a slight decrease from the 8.89 million job openings in December, according to new data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics released Wednesday. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg had expected 8.85 million openings in January.

Again, these are narrative arcs moving in opposition to one another.

Of course, there were also the corporate media outlets that dispensed with the dichotomies and simply said the labor markets remain strong.

U.S. job openings barely changed in January but remained elevated, suggesting that the American job market remains healthy.

The Labor Department reported Wednesday that U.S. employers posted 8.86 million job vacancies in January, down slightly from 8.89 million in December and about in line with economists’ expectations.

This is an easy narrative to promote when one proceeds from the assumption that the job openings figure represents actual labor demand.

US job openings remained elevated in January, suggesting demand for workers is still strong.

Available positions edged lower to 8.86 million from a downwardly revised 8.89 million reading in the prior month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, known as JOLTS, showed Wednesday. Hiring and layoffs also ticked down.

However, that assumption has been easily challenged—and I have challenged that assumption—for the past couple of years at least.

If the job openings data is suspect—and it is—then actual labor demand in the US is not what it is claimed to be, and we must assess it as being much weaker than the narrative suggests.

The biggest challenge to the “strong labor market” narrative is not that job openings have trended down since early 2022, but that hiring and separations both have also trended down.

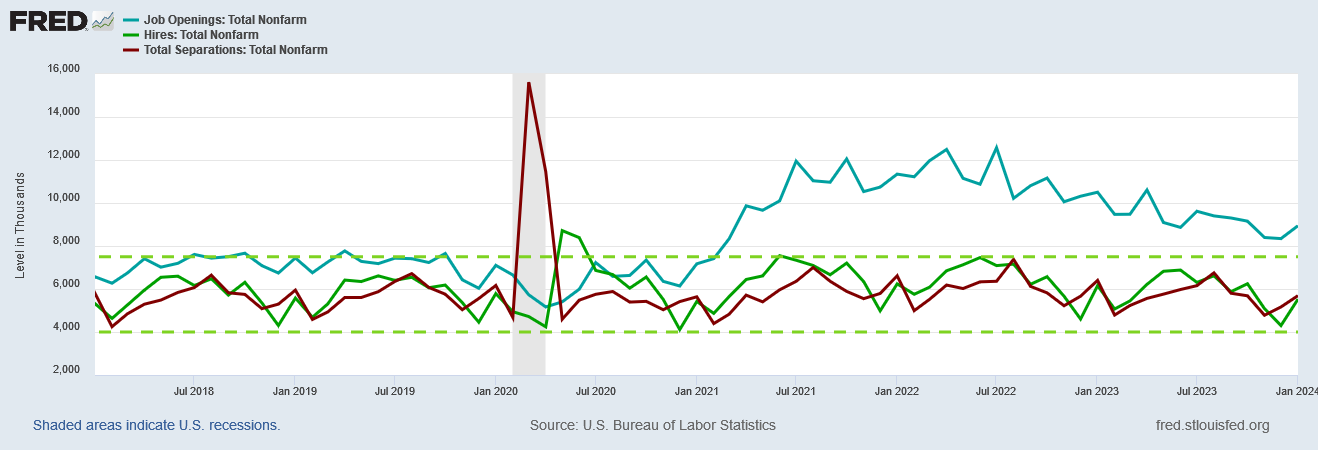

Even if we look at the raw data, while reported job openings, hires, and separations are all lower than their respective peaks, hires and separations remain within the same broad range of activity as before the Pandemic Panic Recession.

With no significant upward movement on raw hires despite the increased number of openings in 2021, we straight away have to consider the possibility that the job openings data is at the very least inaccurate.

Moreover, when we delve into seasonally adjusted job openings by job category, we see the top categories—Trade, Private Education and Health, and Leisure and Hospitality—all trending down, while Government job openings are more or less unchanged, as is Construction.

While we should not be surprised that different economic sectors would see different trends on jobs, we should be concerned that an indisputably non-productive economic sector—Government employment—is holding its own while the most accessible sectors have been steadily weakening. Coupled with an incremental decline in Manufacturing job openings, these trends suggest a shift in overall employment that is far from healthy overall.

The trend pattern is largely the same even with the raw job openings data.

This is not a sign of a “strong” labor market, nor a “tight” one, but one that is, as I have said before, quite “toxic.”

Why neither the “experts” nor corporate media reaches this same conclusion is a speculation I leave to the reader.

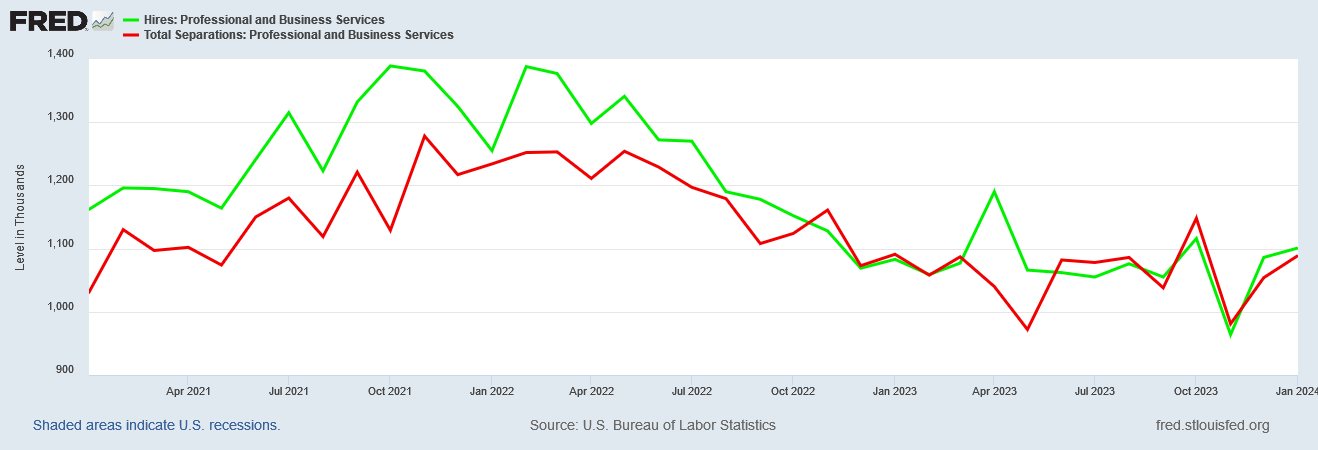

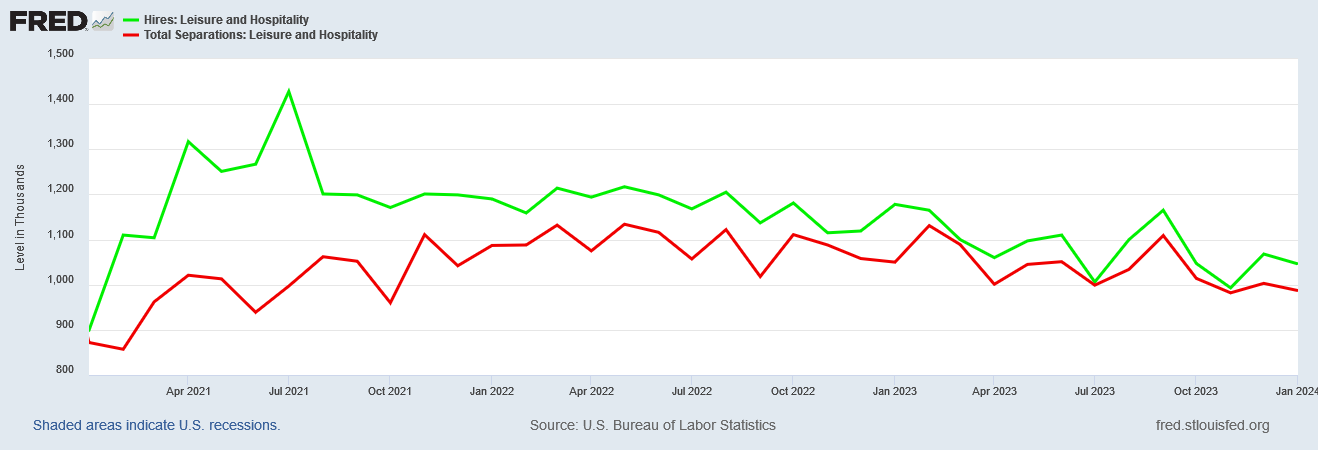

Yet it is not merely that job openings in those top employment sectors is shifting. We are also seeing signs of a “lock-in” effect in that both hiring and separations are declining in tandem.

We see this in Professional Services.

We see this in Leisure and Hospitality.

We see this in Trade:

Not only are firms hiring fewer and fewer workers, fewer and fewer workers are leaving their jobs—both in terms of voluntary quits and involuntary layoffs.

Indexed to January 2021, the seasonally adjusted data for quits and layoffs both show a steady decline in both since at least the start of last year, and for quits since early 2022.

Not only are workers reluctant to leave, employers are reluctant to let them go.

Yet this is setting up a broadly arbitrary labor constraint, which is exacerbated by the overall labor force declining in recent months, even as those not in the labor force have remained broadly constant since 2021.

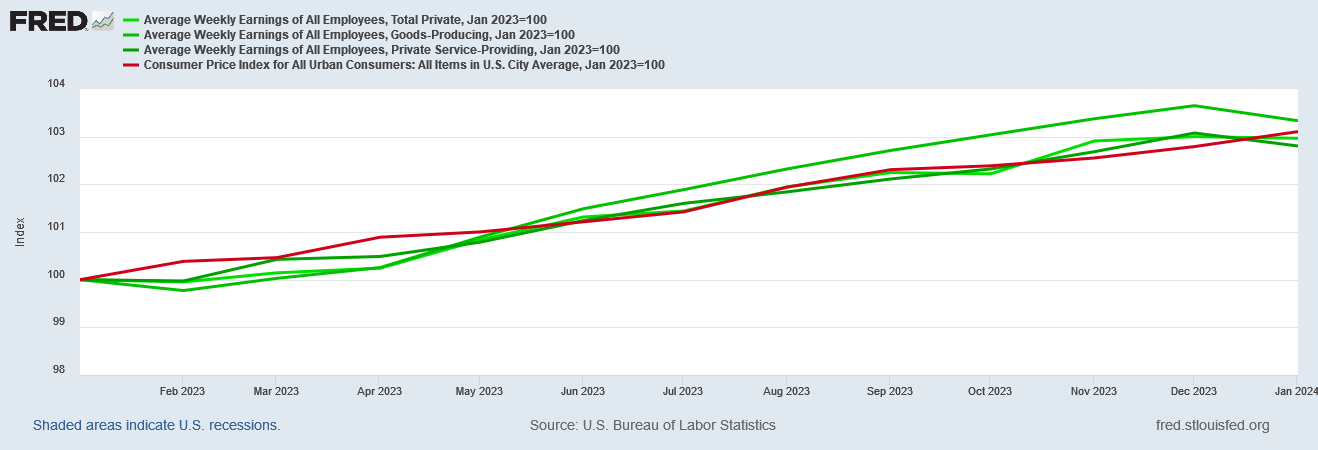

In an healthy labor market, these constraints would be marked by real income growth within the workforce. Yet when we index both Average Weekly Earnings and the Consumer Price Index to January of 2023, we see problematic real income growth at best, and a decline in real incomes at the end of 2023.

This runs counter to the dynamic we would expect to see when there is strong demand for labor that exceeds current labor supply. Instead, this is more resembling the “lock-in” effect we see in residential housing, where historically high home prices relative to incomes are preventing both otherwise prospective homebuyers from entering the market and otherwise prospective home sellers from adding to available housing inventory by putting their homes on the market.

The result is not a “healthy” labor market, any more than it is a healthy real estate market, as the contraints on both supply and demand sides of the equation are essentially causing the markets—labor in the one case and real estate in the other—to “seize up”, resulting in a contraction of the overall market itself.

This is the real takeaway from the muddle January JOLTS report. We should not be looking at whether the headline data shows job growth or job loss, or whether job openings indicate actual labor demand.

Rather we should be concerned that the slowdown in hiring is being matched by a slowdown in terminations, and the combination of the two trends is contributing to a decline in real wages even as inflation is threatening to resume rising once more.

Fewer actual hires regardless of the number of reported job openings represents a reduced opportunity for workers to boost their wages by changing jobs—the one sure leverage every worker has in wage negotiations. Fewer actual separations reduces the number of actual job openings to be filled regardless of what the reported job openings data shows, if only because the openings that would otherwise be created by the separations are no longer happening.

Without a true increase in labor demand—which would be represented by rising hires and declining separations combined (especially if there was a rise in Quits and a drop in Layoffs)—there is little to provide real upward pressure on incomes, thus we see real incomes slipping in December of last year.

What we are seeing in the US is a steady erosion of labor markets themselves. That is the true takeaway from the January JOLTS report. Not only is that bad news, but that corporate media is either unable to see it or unwilling to say it is itself terrifyingly bad news.

When no one will see or admit to seeing what a problem is, solutions are immediately rendered impossible. At present, neither corporate media nor the labor “experts” are willing to see or willing to admit what the data actually shows about US labor markets.

There is no way this does not end well.

My 18 year old son has been trying to get a low paying job of any kind for many months. He has no strikes against him, yet almost zero replies to his applications. Thanks for another truthful post.

Every auto insurance renewal I have received in the last 12 months, have increased by 25%!